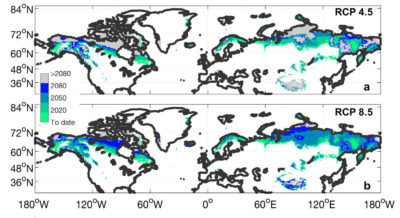

Areas that have already warmed up enough for cold temperatures not to be a limiting factor in plant growth (green), or are projected to be too warm in the coming decades. Trevor Keenan and William Riley/Berkeley Lab

For centuries, frigid temperatures in places like the Arctic and the Himalayas have significantly limited plant growth, restricting it to short periods of time during the year or to species that could survive such harsh conditions. But new research has found that over the past 30 years, the areas across the globe where cold temperatures limit plant growth have declined by 16 percent. By 2100, they could shrink by an estimated 80 percent.

The new study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, examines 30 years of satellite data showing the ebb and flow of plant growth in cold areas such as Alaska, the Arctic, and the Tibetan Plateau. It is the latest study in a surge of research tracking how climate change is expanding plant growth in the world’s coldest regions, particularly in the Arctic, an area that is warming two to four times faster than the rest of the planet.

The scientists’ findings show unrestricted plant growth in areas that advanced climate models didn’t forecast. The research suggests that climate projections “may have significantly underestimated changes in the Arctic ecosystem, and climate models will need to be improved to better understand and predict the future of the Arctic,” lead author Trevor Keenan, a scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Earth & Environmental Sciences Area, said in a statement.

By the year 2100, Keenan and his colleagues estimate that only 20 percent of vegetated land in the northern hemisphere will still be limited by cold conditions. And with earlier springs, plants will grow sooner and in unexpected places.

“Although the greening might sound like good news as it means more carbon uptake and biomass production, it represents a major disruption to the delicate balance in cold ecosystems,” said Keenan. “Temperatures will warm sufficiently so that new species of trees could move in and compete with vegetation that had previously dominated the landscape. This change in vegetation would also affect insects and animals that relied on native vegetation for food.”