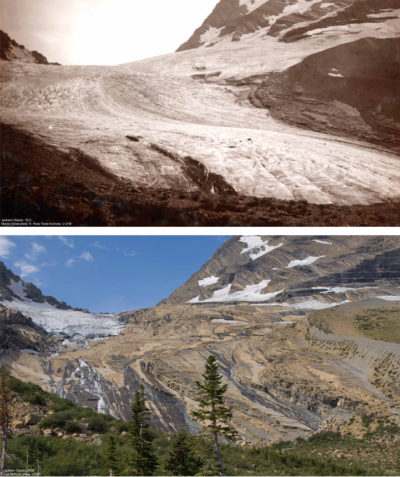

Of the 150 glaciers that existed in Glacier National Park in the late 19th century, just 25 remain, including the Jackson Glacier, seen here in 1911 (top) and 2009 (bottom). M. Elrod, University of Montana. USGS/Lisa McKeon

America’s national parks are warming up and drying out much faster than the rest of the United States, according to a new study on the impacts of climate change on U.S. parks published in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The changing conditions are threatening protected ecosystems from the Everglades in Florida to Denali National Park in Alaska.

The study found that the 417 protected areas in the U.S. national parks system warmed an average 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) between 1885 and 2010 — twice the average U.S. rate — with the most significant temperature increases happening in Alaska. Annual precipitation in parks, which cover a combined 85 million acres, declined 12 percent over the same period, compared to a 3 percent average drop across the U.S.

If nations fail to curb greenhouse gas emissions, known as the “business as usual” scenario, temperatures in U.S. national parks would increase 3 to 9 degrees Celsius by 2100, the study concluded. But the study’s authors stress that drastic reductions in emissions could reduce warming in national parks by as much as two-thirds.

“That’s the hopeful message here,” Patrick Gonzalez, a forest ecologist at University of California, Berkeley and lead author of the new study, told the Miami Herald. “Reducing greenhouse gas emissions can save our parks from the most extreme heat.”