At first glance, these nine sites scattered across the globe seem unremarkable. A peat bog in Poland’s Sudeten Mountains. Searsville Lake, in California, and Crawford Lake, in Ontario. A stretch of seafloor in the Baltic Sea, a bay in Japan, a water-filled volcanic crater in China, an ice core drilled from the Antarctic Peninsula, and two coral reefs, in Australia and the Gulf of Mexico.

But these sites share a significant characteristic: they are all finalists in a remarkable scientific competition that’s expected to announce a winner in the next few weeks. The selected location will — if accepted by the International Union of Geological Sciences, the scientific body that names the Earth’s eras and epochs — both define and represent what scientists are calling the Anthropocene, a new geological epoch that reflects how profoundly humans have altered the planet.

While naturalists and scientists have pondered humanity’s impact on the Earth for centuries, it took until 2000 for the term Anthropocene to gain traction, propelled into the public by Paul Crutzen, a Dutch-born atmospheric chemist who, in 1995, shared a Nobel Prize for research on the depletion of the planet’s ozone layer, and the American ecologist Eugene Stoermer. In 2009, the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG) was formed to determine if a new epoch — marked by human-caused changes — was, indeed, warranted.

“We see a clear, abrupt, and global transition from the previous Earth epoch to something new,” says a geologist.

Human-made climate change is one of many reasons given by the working group to support its case for the Anthropocene. Humanity has also flooded the planet with synthetic chemicals and new radioactive isotopes that will be measurable far into the future, the group argues, and has derailed the natural course of evolution by moving species between continents. In this long view, cities, industrial sites, tunnels, and mines are geological formations in their own right, packed with “techno-fossils” that will long outlast current civilizations.

While almost all of science accepts the severity of recent environmental change, some geologists oppose framing it as a new geological epoch. Debate is ongoing, but after painstakingly compiling and publishing evidence, the 40 scientists of the AWG have determined that the Anthropocene is sufficiently distinct from the Holocene, which began 11,700 years ago.

“We see a clear, abrupt, and global transition from the previous Earth epoch to something new,” says Colin Waters, the AWG’s chair and a former member of the British Geological Survey.

While Crutzen and Stoermer originally proposed the onset of the Industrial Revolution as the Anthopocene’s starting point, scholars continue to debate when human impacts became significant enough to change the chemical composition of sediments and rocks, the metrics of epochal change. After much deliberation, the AWG homed in on the 1950s.

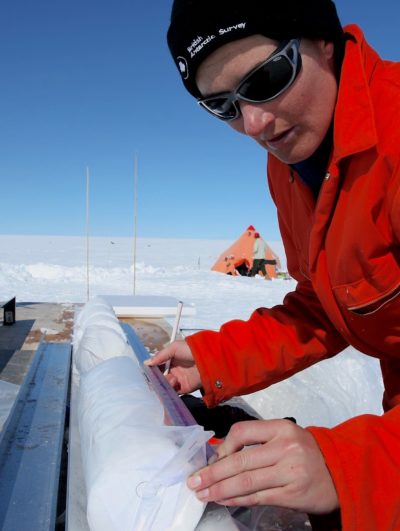

Paleoclimatologist Liz Thomas examines an ice core gathered from Palmer Land on the Antarctic Peninsula. Alistair Simpson / British Antarctic Survey

That’s when a wave of nuclear tests released exotic radioactive elements and isotopes into the atmosphere, and their fallout settled into soils and sediments. The 1950s also marked the beginning of rampant consumption, which injected millions of tons of plastic, processed metals, and synthetic chemicals into the Earth’s systems.

Before the Anthropocene can be officially proclaimed, the AWG must name a single site that permanently captures the epoch’s novelty.The scientific markers include the presence of fly ash and carbon isotopes typical of fossil fuel combustion, increased levels of nitrogen and phosphorus — two elements used in fertilizers — or radioactive elements and isotopes previously absent from the geological record. The site will be declared a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), and it will play a similar role for geology as type specimens, housed in museums, do for describing species of plants and animals.

Other chapters in Earth history have their own GSSPs. The onset of the Jurassic period, for example, is represented by a site in the Austrian Alps where certain species of ammonites and foraminiferes first appear as fossils. Such sites — there are scores of them around the world — are marked with a “Golden Spike” rammed into the rock and an explanatory sign.

According to the rules of geology, a GSSP site needs to meet a long list of criteria. Most importantly, it needs to preserve indefinitely the most typical changes in the chemical composition of sediments and rocks, or in the organisms that have turned into fossils. Sites with a high risk of being washed away or disturbed by either animals or humans are not suitable. Also, a site must be adequately thick and accessible, so it can be examined by scientists.

Of course, there are plenty of places that reflect how humans have altered the biosphere and its geology — including megacities, with their glomerations of minerals, metals, asphalt, glass, and eroded landscapes. A GSSP, however, needs to show characteristics that can be found worldwide, not just in particular spots.

The Ediacaran Period, which ended some 540 million years ago, is marked by a gold spike in the Flinders Ranges of South Australia. James St. John

Once the call for proposals went out in 2019, scientists began sifting through data from past expeditions and measurement campaigns. Some sites were quickly discarded, including Berlin’s Teufelsberg, an 260-foot-high hill made of rubble from World War II and municipal waste. “Such a manmade elevation looked like a good candidate, but then it turned out that this hill was created directly on sand from the Pleistocene,” says Reinhold Leinfelder, a Berlin-based biogeologist and member of the AWG. “The Holocene was totally missing, and that’s not good for a reference point, [which] needs to offer a continuous geological record.”

After much careful vetting, the contest has now been narrowed to nine sites, and the researchers behind each candidate have presented their site’s special features in scientific publications and to the AWG’s twenty-three voting members.

The Śnieżka peatland, situated 4,700 feet above sea level in the Sudeten Mountains in southern Poland, looks like a natural bog. But it tells a history of human interference, says geologist Barbara Fiałkiewicz-Kozieł of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. According to her analysis, from about 1950 on, the bog shows “sharp changes in the deposition of multiple, independent geochemical markers” reflecting fossil fuel combustion, industrialization, and nuclear weapon tests, along with signals of climate change.

Should the Anthropocene be formally recognized, the winning site will act as a stark reminder of human impact.

Francine McCarthy, a micropaleontologist at Brock University, in Ontario, reports that the lakebed under Crawford Lake, in Ontario, “is the only site with undisturbed annual laminations over centuries,” including remains from an Indigenous settlement, European colonization, Canadian logging operations, and modern agriculture. She stresses that beneath the lake, “there are no burrowing organisms to disturb the sediments, allowing the precise calendar age of sediments to be determined by layer counting, just like tree rings.”

The team proposing Searsville Lake, south of San Francisco, emphasizes the site’s human origins. “Searsville is a compelling paradigm for the Anthropocene because the construction of a dam … created this depositional environment,” says Allison Stegner, a palaeobiologist at Stanford University. She describes the lake’s sediments as an “exceptionally detailed Anthropocene archive accumulated via natural geologic processes” with layers of plutonium-239 and plutonium-240 datable to individual seasons of specific years. Many different chemicals typical of human activity have been blown and deposited here by Pacific Ocean winds, she says, which “means they originate from all over the planet and constitute a repository of global dimensions.”

In China, geologist Yongming Han, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, submitted a former volcanic crater called Sihailongwan Maar. While mercury does occur naturally, here its levels increased sharply after 1860, in line with industrialization and the burning of fossil fuels, which contain the heavy metal.

Searsville Lake, near San Francisco, contains layers of plutonium datable to individual seasons of specific years. Sundry Photography / Alamy Stock Photo

In Japan, paleobiologist Michinobu Kuwae, of Ehime University, has submitted Beppu Bay, located on Kyūshū Island. Surrounded by urban sprawl, spas, chemical industries, and fruit orchards, the bay is a microcosm of humanity’s impact. Kuwae has identified a significant increase in nitrogen and phosphorus flowing into the bay from anthropogenic sources. The nutrients have spurred the growth of dinoflagellates, a phytoplankton known to thrive in conditions of marine ecological degradation. Kuwae has suggested that the increase of dinoflagellates could be a significant signifier of the new epoch.

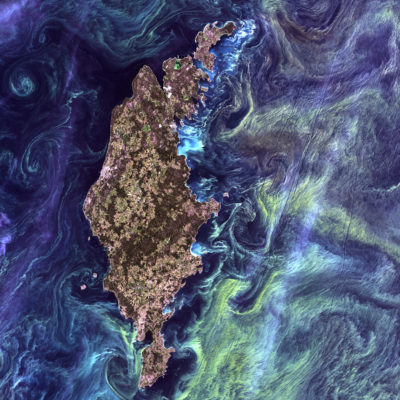

Two scientists from Germany’s Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research have taken a core sample at a depth of 790 feet in the Baltic Sea that shows a pronounced change in color. The oldest layers of sediment “were generally well-oxygenated, mixed by organisms, and of a homogenous, light gray color,” says senior scientist Jérôme Kaiser. After being “significantly impacted by human activity in the mid-1950s,” he adds, the core turned dark “due to a significant increase in the content of organic matter preserved in the sediments.” The sharp color change was caused by a huge influx of nutrients from agriculture and the spread of so-called “dead zones,” where a lack of oxygen prevents the degradation of organic matter.

Clearly, the most beautiful of the sites that might symbolize the Anthropocene are two coral reefs. North Flinders Reef lies 90 miles north of the main band of the Great Barrier Reef, off Australia’s northeastern coast. West Flower Garden Bank in the Gulf of Mexico is considered one of the healthiest coral reefs in U.S. waters, with 50 percent live coral coverage. Both sites look untouched by humans and are far removed from cities and industrial sites. But when geologists took samples from the coral reef structures, they discovered evidence of human impact.

A satellite view of an algae bloom off the Swedish island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. Such blooms are fueled by fertilizer runoff. NASA / USGS

“North Flinders Reef has been impacted by humans since the end of the 19th century through ocean warming, changes in ocean salinity and nutrient cycles, and carbon uptake from [burning] fossil fuels,” says Jens Zinke, a paleobiologist from the University of Leicester, who compiled the proposal. Kristine DeLong, a marine scientist at Louisiana State University, examined a sample drilled at a depth of 70 feet at West Flower Garden Bank, a 10-hour boat ride from the mainland, and found evidence of nuclear explosions, fertilizer, and the burning of fossil fuel.

Even the continent farthest from human population centers now tells the story of the Anthropocene. Liz Thomas, a paleoclimatologist with the British Antarctic Survey, has nominated a site in the Palmer Land region of the Antarctic Peninsula. The closest area of human activity is a scientific research station more than 400 miles away, she says. Yet when she and her colleagues drilled and extracted an ice core there in 2012, they found radioactive and chemical traces similar to those in other candidate sites, though at lower concentrations. Because the oldest layers of her core contain bubbles of air with much lower concentrations of CO2 and methane than the current atmosphere, she says, her site offers a “truly global perspective for the Anthropocene.”

Naming one representative place is the AWG’s last big task before handing matters over to a senior group of scientists in the International Commission on Stratigraphy, the timekeepers of Earth’s history. Should the Anthropocene later be formally recognized by geology’s top scientific body, the International Union of Geological Sciences, the winning site will act as a stark reminder of human impact.

The West Flower Garden Bank in the Gulf of Mexico contains evidence of nuclear explosions, fertilizer, and the burning of fossil fuel. NOAA via Flickr

The scientists who have submitted proposals hope that giving a single site this status might raise awareness of threats to ecosystems and the need to preserve them. Barbara Fiałkiewicz-Kozieł hopes that the GSSP title for the Polish bog she has nominated would be “motivation for better protection of peatlands in general.” Kristine deLong, who submitted West Flower Garden Bank coral reef, says that the still-healthy reef will “hopefully be a survivor in 100 years, such that divers in the year 2100 will see a live coral and not a dead coral as the GSSP.”

As chair of the Anthropocene Working Group, Colin Waters is neutral on which site ought to represent the Anthropocene and is focused on organizing a well-informed vote that leads to a 60 percent majority for the winning site. If the International Union of Geological Sciences formally proclaims the Anthropocene, Waters thinks, the public will take notice.

“It is a big step if the most important geological bodies confirm, after long consideration, how radical the change in the geology of the planet is due to us as a human species, and that the crucial changes have taken place within 70 years,” he says. The recognition would also make it clear “that we cannot simply return to the Holocene world.”