The war over the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) — one of the most contentious and enduring environmental fights in U.S. history — is once again heating up.

Congress is considering a budget bill that permits oil drilling throughout the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge. With Republicans controlling the executive and legislative branches of government, proponents like Alaska Republican Senator Lisa Murkowski believe now is the best chance in decades to develop the refuge.

The debate over drilling in ANWR — a wilderness area nearly as large as South Carolina — has long pitted protecting this pristine environment against American energy security and creating jobs. But behind these talking points is a material infrastructure, the 800-mile Trans-Alaska Pipeline System, that has been incentivizing Arctic development for decades.

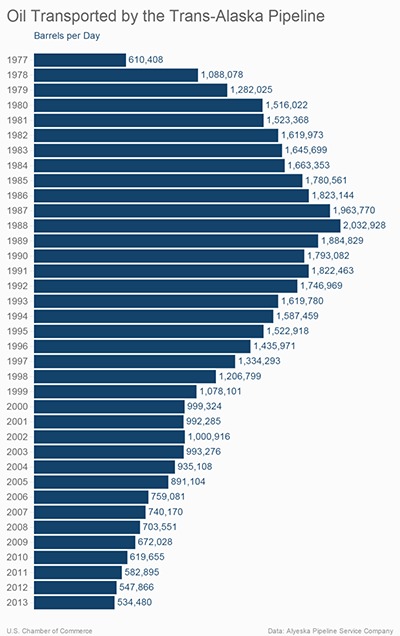

The truth is that the need to keep feeding the 40-year-old pipeline with oil is a key factor behind the current drive to open ANWR to fossil fuel drilling. The volume of oil flowing through the Alaska Pipeline has fallen sharply in recent decades, from a peak of two million barrels of North Slope oil a day in 1988 to 500,000 barrels a day last year. That steep reduction has created numerous technical problems, including a buildup of ice and paraffin wax (naturally found in crude oils) that hinders the easy passage of oil. One solution to the sluggish pipeline flow? Pump more oil into it, hence the drive by Congress and the Trump Administration to drill in ANWR and the nearby National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPRA).

From its earliest stages, government and industry planned to use the pipeline to open new areas of the Arctic to development.

As a result, the nation is now confronted with a great irony: The Alaska Pipeline was approved and built because the nation needed the oil following the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo, but decades later, when the U.S. has abundant supplies of cheap oil and natural gas, it is the pipeline itself that demands ever-more petroleum. That perverse impetus to start drilling oil in these unparalleled Alaskan wilderness areas will — along with projects like the Keystone XL Pipeline — keep the U.S. pumping, transporting, and burning oil for decades to come, even as the world rapidly warms.

Environmentalists and climate scientists contend that now is precisely the moment when the nation should be pivoting away from a major expansion of oil drilling. The rapid growth of wind and solar power, an emerging electric vehicle industry, and increasing alarm over climate change all argue for keeping Arctic oil in the ground.

Alaskans have dreamed of developing Arctic hydrocarbons since the 1940s, when the U.S. Navy discovered several small oil and gas deposits on the North Slope, in what today is the NPRA. Yet these modest discoveries did not justify the high costs of building an oil pipeline across the perilous permafrost.

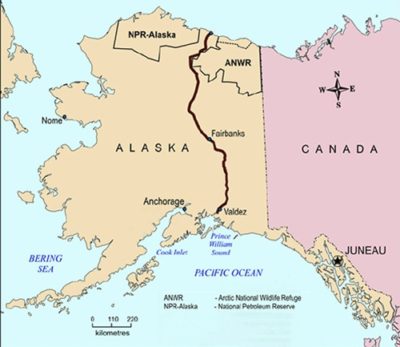

That calculation changed in 1968 when ARCO discovered the massive Prudhoe Bay oil field — the largest in North America — and joined with a consortium of the world’s largest oil companies (soon to be named Alyeska) to construct an 800-mile pipeline from the North Slope to Valdez, Alaska. From the earliest stages of the pipeline’s design and construction, government officials and the oil industry planned to use the new energy infrastructure system to open new areas of the Arctic to development.

In 1970, M.A. “Mike” Wright, the CEO of Humble Oil (soon to be renamed Exxon), delivered extemporaneous remarks to a government task force and offered a rare glimpse of the oil industry’s plans for Arctic development. Wright explained that the industry committed to a 48-inch-diameter pipeline in part because it anticipated drilling offshore in the Arctic Ocean and restricted onshore areas, including the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Production from these areas would be necessary to realize the pipeline’s optimum daily flow. Wright’s statements were not only the first public announcement that the oil industry wanted to drill in ANWR, but a revelation that the pipeline’s design was intimately tied to extracting oil from it.

Alyeska’s planned pipeline collided with an ascendant environmental movement that sought to protect Alaska’s wilderness and stop oil pollution. The contentious four-year legal battle became America’s first environmental fight over pipelines. But the fallout from the Arab Oil Embargo eventually spurred Congress to approve the pipeline, and Alyeska set to work constructing the $8 billion dollar Arctic artery — one of the largest private industrial projects in American history — from 1974 to 1977.

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline runs 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay in the north to the port of Valdez in the south. U.S. EIA

The construction of the pipeline charted a collision course with ANWR, which was established in 1960 and encompasses a breathtaking landscape that descends from the 9,000-foot peaks of the Brooks Range to the Arctic coastal tundra, where tens of thousands of caribou calve their young, polar bears den, and numerous species of waterfowl breed. As the only infrastructure for exporting North Slope crude to market, the Alaska Pipeline transformed the North Slope’s oil reserves into economic resources that could be extracted and brought to market. With the completion of the pipeline, the oil under the Arctic Refuge became tremendously enticing to the oil industry, the federal government, and the state of Alaska.

Throughout the 1980s, Alaskan politicians became increasingly focused on drilling in ANWR and the fortunes that might flow into state coffers. The pipeline transformed the young state’s political economy and brought a windfall of petroleum profits. By the early 1980s, Alaska not only used oil revenues to fund 90 percent of its state government, it also created the innovative Alaska Permanent Fund to save for the future and grant each citizen a yearly dividend. But then oil prices crashed in 1986, sending the state’s economy into a severe depression. The oil industry and the State of Alaska argued that opening the Arctic Refuge would improve the economy, provide thousands of jobs, and bolster American energy security.

The Alaska Pipeline is now pushing far less oil through its pipe than engineers in the 1970s designed the system to handle.

And so, rather than American consumers, the pipeline itself was now the object of demand. Drilling in the Arctic Refuge was now necessary to refuel the pipeline. The oil industry’s ambitious four-foot-wide pipeline design, which assumed future drilling in ANWR, now suffered because its capacious size struggled to cope with modest oil volumes. In short, the pipeline’s flow problems are the product of the industry’s own design and its belief that large segments of the North Slope — including ANWR — would eventually be open for drilling.

As the flow of the pipeline declines, Alyeska is forced to spend more time, money, and energy ensuring the oil remains hot and flows smoothly. The company now heats the oil at several pump stations, runs mechanical cleaning devices more often, and adds methanol to facilitate flow. This makes every barrel shipped through the pipeline more expensive. In addition, the higher operating costs are another reason for Alyeska and its owner companies to seek increased oil production on the North Slope.

The flow of oil through the Alaska Pipeline peaked in 1988 at 2 million barrels per day and has since fallen to roughly 500,000 barrels per day. U.S. Chamber of Commerce

As Tom Barrett, Alyeska’s president, recently explained, “The reserves are there, and just getting the obstacles out of the way to get them in the pipe is the simplest solution to a lot of our challenges.”

Alaska’s elected officials also started to worry about the economic lifespan of the state’s cash cow. As the pipeline reached peak flow in 1988 and began to decline, the oil industry increasingly argued that the Alaska Pipeline was not designed to transport small volumes of Arctic oil.

The problem is that when lower volumes of oil are shipped through the system, the oil moves more slowly. As the oil slows, it produces less friction and cools faster, causing a buildup of oil wax and ice. This combination of wax and ice can coat critical valves, accumulate at the bottom of the pipeline, and plug up pumping stations — all costly to repair.

When the pipeline shipped more than two million barrels per day at its peak, the oil took only four days to make the transit from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez. Today, with flow at roughly 500,000 barrels per day, the transit takes 15 days. The Alaska Pipeline is now pushing far less oil through its pipe than engineers in the early 1970s designed the system to handle.

The oil industry and the state of Alaska foresaw these “low throughput” problems beginning in the late 1980s. In 1987, Exxon argued that drilling in ANWR offered the best chance “to keep the pipeline full and supply America’s energy needs.” A U.S. Department of Energy report added weight to Exxon’s arguments by warning that the Alaska Pipeline could be permanently closed due to low flow by 2010.

This precarious situation is exacerbated by the fact that the 1974 right-of-way agreement requires Alyeska to dismantle the pipeline and restore the land when the pipeline ceases operation. Since the pipeline is the only existing infrastructure to export North Slope crude, its closure could well shutter U.S. Arctic oil extraction.

Environmental organizations dispute Alyeska’s claim that more oil is essential for the safe operation of the pipeline, but there is no doubt that concern over low flow has energized efforts to expand Arctic oil extraction. These dynamics help explain the motivation behind many of the recent Arctic drilling campaigns, from BP’s Liberty project to Shell’s efforts in the Chukchi Sea.

Caribou graze in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Getty Images

In 2015, President Obama’s Interior Department recommended that virtually the entire Arctic National Wildlife Refuge be protected as wilderness. Alaskan politicians were predictably outraged. “It looks like the goal is to shut down the pipeline,” Senator Murkowski said.

On January 5, 2017, just before Donald Trump’s inauguration, Alaska’s senators introduced a bill to open the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge to oil and gas development. Murkowski and Alaska’s other U.S. Senator, Dan Sullivan, released a statement declaring that the Alaska Pipeline “is facing more and more challenges from declining throughput. Closure of the pipeline would shut down all northern Alaska oil production, devastating Alaska’s economy and deepening U.S. dependence on unstable countries throughout the world.”

The senators touted that opening the refuge would provide “billions of dollars in federal and state revenue” and “reduce our deficit.” Indeed, congressional Republicans are counting on nearly $1.1 billion dollars in revenue from ANWR drilling over the next decade to fund proposed corporate tax cuts and broader tax reform.

The Alaska Pipeline offers a timely case study of how pipelines drive continued oil extraction and persist far beyond their intended lifespan.

If developing the ANWR is important for the economics of the Republican tax plan, it’s the Holy Grail for a state struggling with a $3-billion-dollar annual budget deficit. Low oil production and prices have severely undermined the state’s finances, not unlike during the 1980s recession. Tapping the Arctic Refuge has long been touted as the cure-all when low oil prices have thrown the state into financial panic.

But Alaska is not only in the midst of a fiscal crisis, it’s on the front lines of the unfolding climate crisis. Alaska has warmed twice as fast as the rest of the planet, with the average annual temperature increasing by 3 degrees Fahrenheit and winter temperatures rising by a far scarier 6 degrees. Arctic summer sea ice has lost 75 percent of its volume and half its extent since 1980.

In a not-so-subtle irony, the pipeline itself is increasingly affected by climate disruption. The permafrost that underlays much of the pipeline is thawing thanks to soaring temperatures. The success of the pipeline in facilitating the combustion of carbon-dense energy is undermining its very foundations.

As the world strives to decarbonize the global economy, the history of the Alaska Pipeline offers a timely case study of how pipelines drive continued oil extraction and persist far beyond their intended lifespan. The Alaska Pipeline not only encourages production by its very presence, but keeping it open demands expanding Arctic drilling to outpace declines from legacy oil fields. While the fate of the Arctic Refuge remains uncertain, the endurance of the Alaska Pipeline may very well ensure that drilling throughout the U.S. Arctic will continue in earnest.

When Alyeska constructed the Alaska Pipeline in the 1970s, it was expected to last 25 to 30 years. This year it celebrated 40 years of transporting Arctic oil. Reflecting on its birthday, a senior executive at Alyeska recently announced, “We’re very confident we’ll get it to last another 40 years.”