Summers in the city can be extremely hot — several degrees hotter than in the surrounding countryside. But recent research indicates that it may not have to be that way. The systematic replacement of dark surfaces with white could lower heat wave maximum temperatures by 2 degrees Celsius or more. And with climate change and continued urbanization set to intensify “urban heat islands,” the case for such aggressive local geoengineering to maintain our cool grows.

The meteorological phenomenon of the urban heat island has been well known since giant cities began to emerge in the 19th century. The materials that comprise most city buildings and roads reflect much less solar radiation – and absorb more – than the vegetation they have replaced. They radiate some of that energy in the form of heat into the surrounding air.

The darker the surface, the more the heating. Fresh asphalt reflects only 4 percent of sunlight compared to as much as 25 percent for natural grassland and up to 90 percent for a white surface such as fresh snow.

Most of the roughly 2 percent of the earth’s land surface covered in urban development suffers from some level of urban heating. New York City averages 1-3 degrees C warmer than the surrounding countryside, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – and as much as 12 degrees warmer during some evenings. The effect is so pervasive that some climate skeptics have seriously claimed that global warming is merely an illusion created by thousands of once-rural meteorological stations becoming surrounded by urban development.

Climate change researchers adjust for such measurement bias, so that claim does not stand up. Nonetheless, the effect is real and pervasive. So, argues a recent study published in the journal Nature Geoscience, if dark heat-absorbing surfaces are warming our cities, why not negate the effect by installing white roofs and other light-colored surfaces to reflect back the sun’s rays?

Lighter land surfaces “could help to lower extreme temperatures by up to 2 or 3 degrees Celsius,” says one researcher.

During summer heat waves, when the sun beats down from unclouded skies, the creation of lighter land surfaces “could help to lower extreme temperatures… by up to 2 or 3 degrees Celsius” in much of Europe, North America, and Asia, says Sonia Seneviratne, who studies land-climate dynamics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, and is co-author of the new study. It could save lives, she argues, and the hotter it becomes, the stronger the effect.

Seneviratne is not alone in making the case for boosting reflectivity. There are many small-scale initiatives in cities to make roof surfaces more reflective. New York, for instance, introduced rules on white roofs into its building codes as long ago as 2012. Volunteers have taken white paint to nearly 7 million square feet of tar roofs in the city, though that is still only about 1 percent of the potential roof area.

Chicago is trying something similar, and last year Los Angeles began a program to paint asphalt road surfaces with light gray paint. Outside the United States, cool-roof initiatives in cities such as Melbourne, Australia are largely limited to encouraging owners to cool individual buildings for the benefit of their occupants, rather than trying to cool cities or neighborhoods.

The evidence of such small-scale programs remains anecdotal. But now studies around the world are accumulating evidence that the benefits of turning those 1 percents into 100 percents could be transformative and could save many lives every year.

Keith Oleson of the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado looked at what might happen if every roof in large cities around the world were painted white, raising their reflectivity — known to climate scientists as albedo — from a typical 32 percent today to 90 percent. He found that it would decrease the urban heat island effect by a third — enough to reduce the maximum daytime temperatures by an average of 0.6 degrees C, and more in hot sunny regions such as the Arabian Peninsula and Brazil.

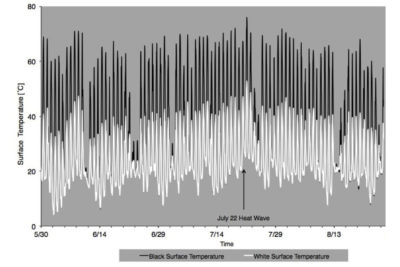

White test plots on the roof of the Museum of Modern Art in Queens, New York, measured 40 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than those painted black throughout the summer of 2011. Gaffin et al.

Other studies suggest even greater benefits in the U.S. In a 2014 paper, Matei Georgescu of Arizona State University found that “cool roofs” could cut temperatures by up to 1.5 degrees C in California and 1.8 degrees in cities such as Washington, D.C.

But it may not just be urban areas that could benefit from a whitewashing. Seneviratne and her team proposed that farmers could cool rural areas, too, by altering farming methods. Different methods might work in different regions with different farming systems. And while the percentage changes in reflectivity that are possible might be less than in urban settings, if applied over large areas, she argues that they could have significant effects.

In Europe, grain fields are almost always plowed soon after harvesting, leaving a dark surface of soil to absorb the sun’s rays throughout the winter. But if the land remained unplowed, the lightly colored stubble left on the fields after harvesting would reflect about 30 percent of sunlight, compared to only 20 percent from a cleared field. It sounds like a relatively trivial difference, but over large areas of cropland could reduce temperatures in some rural areas on sunny days by as much as 2 degrees C, Seneviratne’s colleague Edouard Davin has calculated.

In North America, early plowing is much less common. But Peter Irvine, a climate and geoengineering researcher at Harvard University, has suggested that crops themselves could be chosen for their ability to reflect sunlight. For instance, in Europe, a grain like barley, which reflects 23 percent of sunlight, could be replaced by sugar beet, an economically comparable crop, which reflects 26 percent. Sometimes, farmers could simply choose more reflective varieties of their preferred crops.

Again, the difference sounds marginal. But since croplands cover more than 10 percent of the earth’s land surface, roughly five times more than urban areas, the potential may be considerable.

Reducing local temperatures would limit evaporation, and so potentially could reduce rainfall downwind.

On the face of it, such initiatives make good sense as countries struggle to cope with the impacts of climate change. But there are concerns that if large parts of the world adopted such policies to relieve local heat waves, there could be noticeable and perhaps disagreeable impacts on temperature and rainfall in adjacent regions. Sometimes the engineers would only be returning reflectivity to the conditions before urbanization, but even so, it could end up looking like back-door geoengineering.

Proponents of local projects such as suppressing urban heat islands say they are only trying to reverse past impacts of inadvertent geoengineering through urbanization and the spread of croplands. Moreover, they argue that local engineering will have only local effects. “If all French farmers were to stop plowing up their fields in summer, the impact on temperatures in Germany would be negligible,” Seneviratne says.

“Local radiative management differs from global geoengineering in that it does not aim at effecting global temperatures [and] global effects would be negligible,” she says. It is “a measure of adaptation.”

But things might not always be quite so simple. Reducing local temperatures would, for instance, limit evaporation, and so potentially could reduce rainfall downwind. A modeling study by Irvine found that messing with the reflectivity of larger areas such as deserts could cause a “large reduction in the intensity of the Indian and African monsoons in particular.” But the same study concluded that changing albedo in cities or on farmland would be unlikely to have significant wider effects.

Los Angeles has coated several streets in a light gray paint to reduce road-top temperatures by as much as 10 degrees Fahrenheit. City of Los Angeles Bureau of Street Services

What is clear is that tackling urban heat islands by increasing reflectivity would not be enough to ward off climate change. Oleson found that even if every city building roof and stretch of urban pavement in the world were painted white, it would only delay global warming by 11 years. But its potential value in ameliorating the most severe consequences of excess heat in cities could be life-saving.

The urban heat island can be a killer. Counter-intuitively, the biggest effects are often at night. Vulnerable people such as the old who are stressed by heat during the day badly need the chance to cool down at night. Without that chance, they can succumb to heat stroke and dehydration. New research published this week underlines that temperature peaks can cause a spike in heart attacks. This appears to be what happened during the great European heat wave of 2003, during which some 70,000 people died, mostly in homes without air conditioning. Doctors said the killer was not so much the 40-degree C daytime temperatures (104 degrees F), but the fact that nights stayed at or above 30 degrees (86 degrees F).

Such urban nightmares are likely to happen ever more frequently in the future, both because of the expansion of urban areas and because of climate change.

Predicted urban expansion in the U.S. this century “can be expected to raise near-surface temperatures 1-2 degrees C… over large regional swathes of the country,” according to Georgescu’s 2014 paper. Similar threats face other fast-urbanizing parts of the world, including China, India, and Africa, which is expected to increase its urban land area six-fold from 1970 to 2030, “potentially exposing highly vulnerable populations to land use-driven climate change.”

Several studies suggest that climate change could itself crank up the urban heat island effect. Richard Betts at Britain’s Met Office Hadley Centre forecasts that it will increase the difference between urban and rural temperatures by up to 30 percent in some places, notable in the Middle East and South Asia, where deaths during heat waves are already widespread.

A combination of rising temperatures and high humidity is already predicted to make parts of the Persian Gulf region the first in the world to become uninhabitable due to climate change. And a study published in February predicted temperatures as much as 10 degrees C hotter in most European cities by century’s end.

No wonder the calls to cool cities are growing.

A city-wide array of solar panels could reduce summer maximum temperatures in some cities by up to 1 degree C.

Another option is not to whitewash roofs, but to green them with foliage. This is already being adopted in many cities. In 2016, San Francisco became the first American city to make green roofs compulsory on some new buildings. New York last year announced a $100-million program for cooling neighborhoods with trees. So which is better, a white roof or a “green” roof?

Evidence here is fragmentary. But Georgescu found a bigger direct cooling effect from white roofs. Vincenzo Costanzo, now of the University of Reading in England, has reached a similar conclusion for Italian cities. But green roofs may have other benefits. A study in Adelaide, Australia, found that besides delivering cooling in summer, they also act as an insulating layer to keep buildings warmer in winter.

There is a third option competing for roof space to take the heat out of cities — covering them in photovoltaic cells. PV cells are dark, and so do not reflect much solar radiation into space. But that is because their business is to capture that energy and convert it into low-carbon electricity.

Solar panels “cool daytime temperatures in a way similar to increasing albedo via white roofs,” according to a study by scientists at the University of New South Wales. The research, published in the journal Scientific Reports last year, found that in a city like Sydney, Australia, a city-wide array of solar panels could reduce summer maximum temperatures by up to 1 degree C.

That is the theory, but there are concerns about whether it will always work in practice. Studies into the impact on local temperatures of large solar farms in deserts have produced some contradictory findings. For while they prevent solar rays from reaching the desert surface, they also act as an insulating blanket at night, preventing the desert sands from losing heat. The net warming effect has been dubbed a “solar heat island.”

The lesson then is that light, reflective surfaces can have a dramatic impact in cooling the surrounding air – in cities, but in the countryside too. Whitewashed walls, arrays of photovoltaic cells, and stubble-filled fields can all provide local relief during the sweltering decades ahead. But policymakers beware. It doesn’t always work like that. There can be unintended consequences, both on temperature and other aspects of climate, like rainfall. Even local geoengineering needs to be handled with care.