On New Year’s Day, 1909, a grocer named Julius Fried and his novice drilling crew, the Lakeview Oil Company, spudded a well in the desert valley scrub in the Midway-Sunset oil field, 110 miles north of Los Angeles. For the first 1,655 feet, the well yielded only dust, and then Lakeview ran out of money.

Fried must have gone to his grave wishing his crew had held on just a little longer. On March 14, 1910, the Union Oil Company’s Charlie Woods — nicknamed “Dry Hole Charlie” for his long streak of dusters — struck what he would later describe as an “artery in the earth’s great storehouse of oil.” When his drill bit reached 2,225 feet beneath the surface, Lakeview No. 1 sent up a sudden column of pressurized oil 200 feet into the air. For 544 days, the Lakeview Gusher would defy every effort to contain it, eventually spreading 9.4 million barrels of oil across the valley floor. Less than half of it was recovered. It remains, to this day, the largest oil spill in the history of the world.

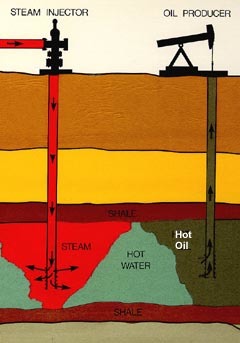

No more gushers spring forth from Midway-Sunset, in California’s parched and scoured San Joaquin Valley. Most of the reserves that rose to the surface like a milkshake through a straw have long since been tapped. What remains are thick hydrocarbons heavy with carbon and depleted of hydrogen, stuck in tectonic rifts that conventional rigs can’t penetrate. Some of it can be coaxed out by first cracking the rock open with an injection of chemical-laced water and sand, the controversial process commonly known as hydraulic fracturing. Much more common in California, however — and in Midway-Sunset especially — is the simpler procedure of liquefying viscous hydrocarbons with an underground shot of steam. As much as 40 percent of California’s roughly 200 million barrels of crude each year begins in the ground as a substance with the consistency of peanut butter. The only way to lift it is to heat it until it flows like honey.

Steam is pumped underground to warm and loosen thick crude oil so it can flow to the surface. U.S. Department of Energy

“California has a lot of low-quality oil resources,” says Adam Brandt, a Stanford University engineering professor who was co-author of a recent article in the journal Nature Climate Change that focused on the intense climate impact of depleted oil fields. “We produce a lot of oil via steam generation, which consumes a lot of energy.” Drillers commonly boil two to four barrels of water, he says, for every barrel of oil.

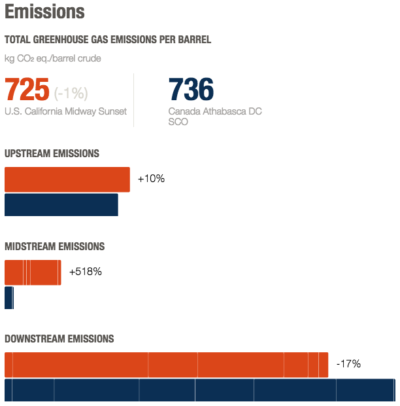

Steam has allowed the Midway-Sunset field to produce long beyond its predicted life and has helped make California the third largest producer of oil in the United States, behind Texas and North Dakota. But it also means that California — the state that stands at the forefront of climate leadership in the United States and that has pioneered renewable energy standards for utilities and a carbon-market for other polluters — also extracts, refines, and burns some of the dirtiest oil on the planet. Each steam-injected well in Midway-Sunset requires the burning of natural gas to produce the necessary steam and lift the oil, which in some cases comes up freighted with as much as 95 times as much water as crude. Then, at the refining stage, producers use more natural gas to transform heavy crude into gasoline. All of those factors combined make the oil from Midway-Sunset only one-and-a-half percent less carbon-intensive than tar sands oil from the Athabascan forests of Alberta.

So far, California’s oil producers have done little to change the way they operate. That’s partly because of scant pressure from state regulators, but also because California’s steam-injected oil has not drawn the kind of attention, from either environmentalists or legislators, that hydraulic fracturing has, even though fracking is used in fewer than one-fifth of the state’s wells. But many climate and energy experts say reforming California’s dirty system of oil extraction is long overdue.

“It’s crazy for an environmentally conscious state to keep putting dirty fossil fuels into producing even dirtier fossil fuels.”

“It’s crazy for an environmentally conscious state to keep putting dirty fossil fuels into producing even dirtier fossil fuels,” says Deborah Gordon, director of the energy and climate program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The state has got to start to break the chain somewhere.”

One way to do that would be to start producing steam using the San Joaquin Valley’s plentiful and consistent supply of solar radiation. Concentrating solar thermal technology uses the sun’s energy to flash water to steam. In an electricity plant, that steam spins a turbine. At a steam-injected oil well, that steam could go straight into the ground. “If just 20 percent of the steam used in California fields was produced with solar,” says David Clegern, spokesman for the California Air Resources Board, “greenhouse gas emissions would be reduced by more than 3 million metric tons annually.” That’s equivalent to taking 643,000 cars off the road for a year.

Another option for greening up oil operations would be to find alternative ways to create the hydrogen that necessarily gets added to heavy oil to make gasoline. “Hydrogen is a really big part of this,” Gordon says. Right now, refineries produce the hydrogen they need by “steam reforming” — pumping steam into methane, the primary component of natural gas. Refineries could instead produce hydrogen with electrolysis, Gordon says, separating hydrogen from oxygen in their own wastewater by subjecting it to an electrical current.

“Will it be cheap?” says Gordon. “No. Are electric vehicles cheap? We’re not talking cheap. We’re talking better and safer for a population that cares.”

Two years ago, Gordon and Jon Koomey, an energy researcher at Stanford University, partnered with Stanford’s Brandt and Joule Bergerson of the University of Calgary to create the Carnegie Endowment’s Oil-Climate Index. Using Brandt’s software tool, the Oil Production Greenhouse Gas Emissions Estimator, they ranked 30 oils worldwide based on the lifecycle emissions of greenhouse gases and other metrics.

A comparison of greenhouse gas emissions produced per barrel of oil from California's Midway-Sunset field and the most carbon-intense type of oil from the Alberta tar sands. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace / Oil-Climate Index

Oil is described as heavy or light depending in part on its hydrogen-to-carbon ratio. It’s also ranked according to an American Petroleum Institute metric known as API gravity. Any oil with an API gravity of 22.3 degrees or less is considered heavy oil, richer in carbon than lighter oils. Volatile light crude from North Dakota’s Bakken Formation has an API gravity of 40 to 50 degrees; it contains so much hydrogen that you can pour it straight into a gas tank. Crude from California’s South Belridge field, north of Midway-Sunset, has an average API gravity of 15 degrees.

Heavier oils not only contain more carbon to begin with, they need more energy to be extracted and refined. A barrel of light crude from the Eagle Ford formation in Texas (API gravity 50 degrees), for instance, emits 38 percent less carbon dioxide from well-to-gas tank than a barrel of bitumen from Alberta, and 37 percent less than heavy crude from Midway-Sunset.

California’s dirty oil hasn’t motivated the same resistance from environmental groups as has oil from Alberta’s tar sands.

California’s dirty oil hasn’t motivated the same resistance from environmental groups as has oil from Alberta’s tar sands. California refineries, with their decades of experience processing heavy crude, are uniquely suited to handle tar sands oil, and activists spent years blocking the import of Canada’s oil to California’s refineries. But environmentalists have not focused as much on California’s own oil, says Anthony Swift, director of the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Canada Project, because fields like Midway-Sunset are on the decline, while Canada’s operations continue to expand. “Canadian companies are still greenlighting new fields,” says Swift. “They expect those fields to continue into production until 2070 or 2080. That’s completely inconsistent with any credible safe-climate scenario.”

Other green groups say they are less interested in improving energy efficiency in oil-field operations than they are in shutting them down. “We don’t support the use of concentrating solar power for oil production, because that production has to be phased out,” says Shaye Wolf, the climate science director at the Center for Biological Diversity in Oakland, California. “We can better spend our resources on clean energy technologies that truly protect our climate and communities.”

Gordon, who in her long career as a chemical engineer has worked for both Chevron and the Union of Concerned Scientists, warns that such a petroleum-free future is a long way off. California likely has decades left of petroleum in the ground, and even if the world switched to solar-powered electric cars tomorrow, petroleum would still be used in plastics, drugs, and jet fuel. “We could be at this another 100 years,” she says, “and oil resources will only get harder to extract.”

The California Air Resources Board does include emissions from steam generation in evaluating oils for its low-carbon fuel standard, and regulators hold oil-field steam generators to stringent standards for traditional pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides and sulfur. But language governing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation fuels, which might have sparked innovation in the oil industry, was written out of a 2015 bill that set higher renewable energy standards for the state’s electric utilities. Carbon-credit prices remain too low for the state’s cap-and-trade program, which was recently extended through 2030, to motivate oil drillers to reduce climate-damaging emissions or limit their use of steam. In fact, the method has only gained popularity during the years of the carbon market’s existence.

Oil pumps in California’s Midway-Sunset oil field. Verifex/Flickr

“Between 2012 and 2015, the amount of steam injected in California oil fields increased by approximately 30 percent,” Clegern says. As long as natural gas prices stay low, “the production of heavy oil will continue in California with or without implementation of solar steam.”

Oil industry spokespeople would not comment about any plans to address the carbon footprint of the crude they draw up from their increasingly depleted wells, referring questions to the industry’s trade group, the Western States Petroleum Association. “The oil and gas industry is constantly testing new technologies to more effectively deliver affordable and reliable energy in the safest possible way,” the organization’s president, Catherine Reheis-Boyd, said in an emailed statement.

Chevron did, however, launch a solar-to-steam demonstration project at one of its San Joaquin Valley oil fields in 2011. The concentrating solar collector aimed 7,600 mirrors at a tower, where a boiler turned water to steam. Built by BrightSource Energy, Inc., of Oakland, it was dismantled in 2014. “The economics were not attractive compared to the current [gas-fired] process,” a Chevron spokesperson told Natural Gas Intelligence, an industry publication.

Another company, Texas-based Cenergy, uses standard, run-of-the-mill solar panels to produce electricity at a Midway-Sunset site operated by Seneca Resources Corporation. The 3.1 megawatt-capacity plant doesn’t directly produce steam, but it is expected to offset 20 percent of the electricity the company uses during its entire extraction process, contributing to the state’s low-carbon fuel goals.

A California company says its solar generator could reduce emissions associated with oil production by 80 percent.

But there may be new hope for solar-to-steam plants. GlassPoint, of Fremont, California, has successfully deployed another kind of concentrating solar thermal technology in the oil fields of Oman, in which troughs of mirrors are used to flash water to steam. According to the company, the solar generator has the potential to reduce emissions associated with oil production by 80 percent. A GlassPoint spokeswoman said the company is weeks away from announcing plans for a California installation.

Change comes slowly in the calcified and competitive petroleum industry, where shareholders’ focus on profits outweigh climate concerns in the long term. Racheting up climate policies, says the NRDC’s Swift, could exert more pressure on oil companies to refom their carbon-intensive practices while California transitions to a clean-energy future.

“There’s not going to be a moment where fossil fuel production stops, and renewable energy begins,” he says. “It’s going to be a transition. An essential part of it is investing in electrical cars. But another part of it is cleaning up existing sources.”