As scientists from around the world tracked the rapid decline of Arctic sea ice in recent years, they couldn’t help but notice that one part of the Arctic basin is a repository for the oldest — and thickest — polar ice. Stetching across northern Greenland and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, this band of reasonably sturdy ice forms as prevailing wind and ocean currents drive sea ice from Siberia, across the Arctic, and up against the opposite shore.

Leading Arctic sea ice specialists believe that this strip of ice could become a crucial ice refuge as summer sea ice all but disappears in most other parts of the Arctic by mid- to late-century. One of those researchers is Stephanie Pfirman, co-chair of the Environmental Science Department at Barnard College in New York City, who, along with several colleagues, presented the concept of the Arctic sea ice refuge at the recent meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

In an interview with Yale Environment 360, Pfirman described how the refuge could become a key habitat for polar bears, ringed seals, and other ice-dependent Arctic creatures. While these species are likely to suffer major population declines in other parts of the Arctic, the ice refuge zone could harbor substantial numbers of these creatures until the end of the 21st century and, possibly, beyond.

The good news, says Pfirman, is that if humanity begins to significantly reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases, the ice refuges could preserve Arctic species and enable them to repopulate the region if ice levels recover in the future.

Yale Environment 360: Can you tell me where the concept of the Arctic sea ice refuge came from?

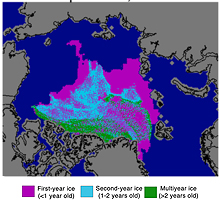

Stephanie Pfirman: With the summer sea ice projected to decline, the more we looked at the models, the more we realized that in the latter half of this century most models project that there will still be some ice. And so that got us thinking. Where will that ice be? And where would it come from? The observations show that right now the oldest ice is right up along the northern flank of Canada and Greenland. The oldest ice has been there for a long time, and we know that from our analysis of the way the ice moves. And it makes sense that it’s there because the winds come from Siberia. They blow across the Arctic, and the Russian currents do, too, and it basically piles up ice in northern Canada and Greenland. So in the future, as you continue to freeze the ocean during the wintertime, the winds will blow that winter ice over toward Canada and Greenland. So it’s likely that you’ll continue to have ice there even when you have less and less ice in the summertime.

Then we looked at the model projections and they were showing the same thing. So there’s a real scientific consensus saying that this is likely to be the place that’s going to have the most persistent ice into the future. So then once you know that, then you say, well, what does that mean?

e360: I want to get into the details of this so-called refuge, but could you first describe the rate of melting, both in terms of extent and thickness, that is driving the necessity to even think about having an ice refuge?

Pfirman: When I first started working on ice up in the Arctic back in 1980 or so, ice tended to be in equilibrium and was around three meters thick. That’s at least twice as thick as it is now.

e360: Throughout the Arctic basin?

Pfirman: Yes, but even more so in this [refuge] area. When you ridge the ice, when you deform it, you pile it up and then you have much, much thicker ice. Ice would form and then it would get transported in this big gyre, the Beaufort Gyre, kind of like a whirlpool, to the one side of the Arctic. And the ice just circulates around and around in that area and can stay there for over a decade.Then on the other side there’s the Transpolar Drift Stream that goes from the middle of Siberia, sweeps all the way across and over the North Pole. So you had these two systems and right in the middle of the two is kind of this dead zone where the ice is very slow and sluggish and it’s up against the Canadian Arctic archipelago and Greenland. And that’s the likely place of the refuge.

e360: And one of your colleagues said that based on the rate of melt and the continued pouring of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, that in the 2030s and 2040s you could see a really precipitous drop of Arctic sea ice?

“A new study says if we do act to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, then it looks like the sea ice can come back.”

Pfirman: Yes. So the [steep] drop that we saw in 2007, something like that had actually been projected by Marika Holland, Cecilia Bitz, and Bruno Tremblay, who had done some work earlier where they had said that there’s no reason why, with the warming that we’re having, the decline of ice has to happen gradually. It could happen precipitously. And those are called rapid ice loss events. They were analyzing a lot of models and they said, you know, there is potential for this to happen and it could result in much diminished ice cover. There’s a really neat new study that just came out [in Nature], which shows that if we do act to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, then it looks like the sea ice can come back. It’s kind of a bookend on our refuge analysis, because what we’re saying is, if we don’t act, what’s the base case? Where is the most persistent ice likely to be? What are the sources of it? But what they did was they said, ‘Well what happens if we do act? What happens if we mitigate?’ And they show that sea ice is likely to return to not-exactly normal levels, but it’s likely to come back.

e360: The two questions that immediately popped into my mind were how big is this so-called refuge and how many sea ice-dependent species throughout the whole Arctic would be able to access it?

Pfirman: It depends on the season, of course. In the wintertime, the ice expands right now to fill the entire Arctic basin. In the spring, it starts melting back and then by September it hits its minimum. And when people talk about an ice-free Arctic, they’re basically saying, when is the ice gone completely in September? And that’s the projection that people are saying — 2050 or so. Because the minimum ice extent is in September. That will happen first. Then it will be [ice-free] in August, September, and October. And then it will progressively spread out from there. In spring, you don’t have the dramatic loss of ice that you have in the summer. It looks like you’ll still have ice in spring for quite a while.

e360: Past mid-century?

Pfirman: Maybe through the end of the century even.

Click to enlarge

e360: Well, let’s project out toward the mid to end of this century if there isn’t mitigation, if temperatures would rise more than two degrees C and if you lose a lot of ice, what size are you projecting that this ice refuge might be year-round?

Pfirman: A lot of people, when they think of what the refuge might be, what comes to mind is this image of a patch of ice with all these animals crowded onto it, kind of like Noah’s Ark. But animals tend to be territorial, and they need some space. So it’s not that you’re going to collect all the polar bears from all over the Arctic and they’re all going to go there and be happy living up close next to each other. What’s more likely is that the bears in this region will do okay and you’ll have loss of habitat for the bears in other places and they will not do okay.

e360: So in a sense you are talking about an ark in that this is almost like triage. If warming continues, you are going to lose a certain percentage of polar bears and ringed seals?

Pfirman: There’s ice-dependent species, which need the ice, and then there’s ice-associated, where they prefer to have the ice. So there’s a whole suite of other species. People have talked about the walrus, for example. The East Greenland walrus likes to feed off of clams on the seabed and those clams are in relatively shallow water depths and there are likely to be a lot of clams in the future. So their main food source is okay. But they like to haul out on the ice and rest and also drift to new feeding grounds. And they eat thousands of clams, so they need to keep moving. When you have a whole bunch of walruses coming to an area, they’re going to deplete the food source and they need to get to a new area, so their preferred mode of transportation is to hitch a ride on some drifting ice and go to another place. And so they’ll also be stressed with loss of ice.

e360: Who first came up with this idea of the Arctic sea ice refuge?

Pfirman: It emerged from several different perspectives. Within the scientific community we’ve known for a while that the oldest and thickest ice is there. And in the modeling community, the projections have been that this is likely to be the place where the ice is going to be located for the longest. But the term “ice refuge” is something that was emerging out of our group as we were talking about this. During past glacial retreats and advances you had refugia where you had populations that were isolated, so that’s a term that people had also used.

e360: And in terms of public policy, as the Arctic opens up in the summer — of course there are large amounts of oil and gas up there. From a public policy point of view, as a scientist, is the goal here to begin making recommendations about resource development staying out of this refuge area?

If you didn’t know this was a special region, you might behave very differently.”

Pfirman: What our goal is in doing this work is to lay the foundation so that people know what the Arctic system has the potential to do.If you didn’t know that this was a special region, you might behave very differently than if you knew it was a special region. Clearly the oldest and thickest ice is likely to be mainly located within Canadian and Greenlandic waters. But the sources of the ice are actually coming from the central Arctic and potentially the [continental] shelf seas. That was the other piece of new work that we have presented, to show how interconnected the refuge is to the rest of the Arctic and saying, okay, if you form ice on the Alaskan and Siberian shelf seas, that ice can get into the refuge area and melt. So it can actually release whatever it’s carrying, be that sediments, pollutants, whatever.

e360: Oil spills?

Pfirman: Oil — that’s right. A lot of the ice is likely to come from the central Arctic, and the central Arctic is a place where people have talked about trans-Arctic shipping. That brings that quite close to what we’re calling the ice refuge.

e360: Speaking of the North Pole, if warming continues that could be ice-free, right? That’s not part of the refuge?

Pfirman: It’s kind of at the outer fringe of it. As the ice is melting back, at some point [the North Pole] is likely to be exposed, as well, if global warming continues.

e360: Did you say that most of the ice now being found in the Arctic is first- or second-year ice?

Pfirman: Yes, and that’s a huge difference. When I first started working, back around 1980, a lot of the Arctic ice was older than five years old. And now there’s hardly any [five-year ice]. It’s diminished incredibly. In 1989, the winds aligned just perfectly and blew the old ice out of the Arctic Ocean through Fram Strait and that left the Arctic ice cover much thinner and more dynamic. Then, of course, if you superimpose a warming trend on that, it basically set the stage for what’s happened since then.

e360: What about [snow]?

Pfirman: Brendan Kelly [of the National Marine Mammal Lab] was talking about snow. What he was concerned about was the snow depth, because the seals need a certain snow depth in order to make their dens. What happens is that you have the snow falling on the ice. And then you need to have some ridging because then when the winds blow you can accumulate enough snow to make a snow cave for the seals.

e360: Where they actually birth their pups?

Pfirman: Right.

e360: And keep their pups warm?

Pfirman: Right.

e360: And without that the pups are too exposed?

Pfirman: That’s right. So you need the special combination of snow with ridged ice. What he’s concerned about is that you have more melting of the ice and you have less ice formation in September, October, November. That’s when a lot of the snow is falling. They did this really interesting analysis where they looked at what the snow is going to be like and even though precipitation is likely to increase, if much of the snow is falling into open water it can’t accumulate on the ice.

e360: From a public messaging point of view, your refuge concept and the recent Nature paper are basically saying that if we can slow the rate of warming, the damage to these ice-dependent species can be somewhat contained?

Pfirman: Right. Both of them are saying that, looking toward the latter half of the century, it makes a lot of sense to act, to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, and also to consider the Arctic as a system, and to really understand how it functions. Because if we make decisions knowing how it works, we’re going to be able to take care of the species that are up there much better than if we don’t know.