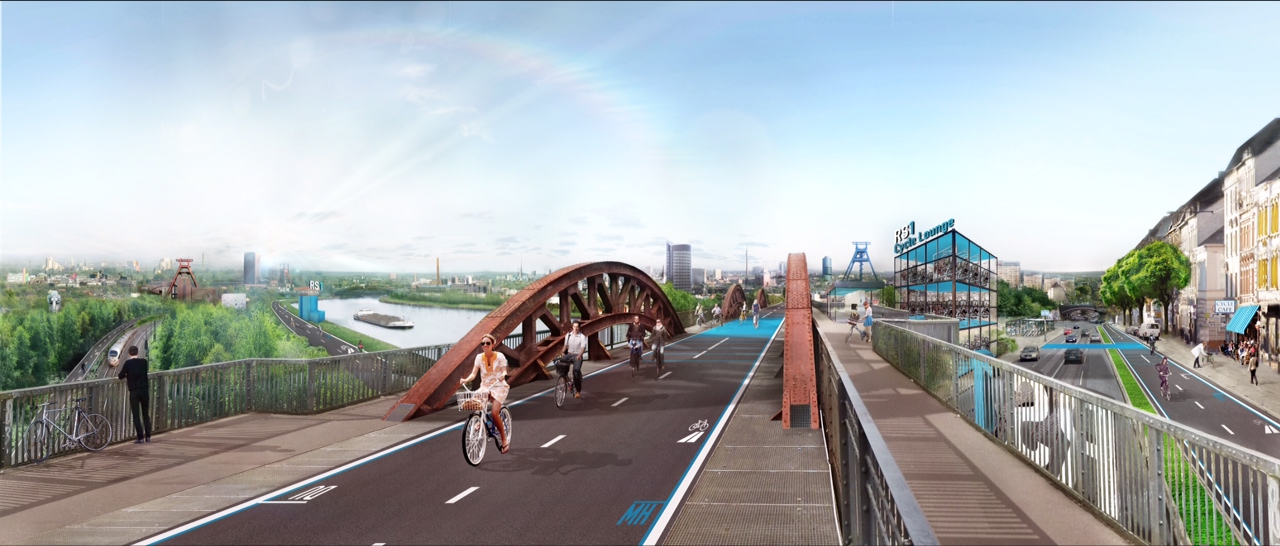

Last November, politicians, environmentalists, and bicycling enthusiasts gathered in Mülheim in Germany’s Ruhr Valley — one of Europe’s major industrial centers — to open the first 11 kilometers (7 miles) of a planned 100-kilometer biking highway that will run from Hamm to Duisburg. Thirteen feet wide and reserved exclusively for cyclists, the bike highway, dubbed RS1, will pass through cities, suburbs, farmland, and industrial areas, and connect four major universities, with part of its path following an abandoned railway line. The bike thoroughfare will also parallel a major highway, the A40, which project organizers hope will entice increasing numbers of the region’s residents to forsake their cars and ride bikes to offices, shops, and schools.

“We will introduce cycling highways as an official new type of infrastructure in our state’s laws,” said the transport minister of North Rhine-Westphalia, Michael Groschek, who called the construction of the bike freeways an “historic moment for transportation policy.”

The Ruhr area, with more than 5 million inhabitants, is spearheading a growing movement across Germany to construct wide, protected, cycling highways designed to encourage ever-greater numbers of people to begin using bicycles as an important mode of transportation. In Berlin, bicycling enthusiasts are building public support for a plan to create a network of at least 100 kilometers of cycling highways connecting the periphery of Berlin with the city center by 2025. If completed, these highways would mark a new era of cycling for the 3.5 million inhabitants of Germany’s capital and beyond.

In Munich, planners are considering a network of 14 proposed bicycle highways and are now moving on developing the first one, which would run between the city boundary and adjacent municipalities to the north. Other cities including Hamburg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg are also in the process of creating this new infrastructure for cycling, known as dedicated highways. A key goal is to get commuters out of their cars.

The push for cycling highways represents a fundamental change in how cities treat bicyclists throughout Germany and in other European countries. For a long time, the Danish capital, Copenhagen, and the Dutch metropolis, Amsterdam, were lone champions of pro-cycling strategies in Europe. But that spirit is now spreading across the continent, and Germany — a leader in renewable energy generation and home to a population with a deeply ingrained conservation ethos — is beginning to play an important role in the cycling revolution.

Until a few years ago, bicycling in Germany was considered a minority pastime and a decidedly hippie-like way of commuting to work.

The push for cycling highways represents a fundamental change in how cities treat bicyclists in Europe.

Today, it has become a mainstream activity considered not only cool, but also something like a duty for anybody who says he or she cares about the environment.

Cycling highways are fundamentally different from usual cycling lanes. Highways are around 4 to 5 meters wide — twice the width of many bike paths — so faster cyclists can overtake slower ones in both directions. High-quality asphalt is often used to enable bicyclists to travel faster. These highways are designed with few or no intersections with major roads, and as few traffic lights as possible — all intended to enable cyclists to travel effortlessly within or among cities and suburbs. Like autobahns, the biking highways are designed to allow travelers to cover large distances without leaving the network.

Attracting commuters is a key goal of Germany’s cycling highways. Traffic experts have found that, on average, most people will use their bicycles for distances below 5 kilometers. “So far, people who use cycling infrastructure for distances of 10 or 15 kilometers are a minority,” says Birgit Kastrup, an urban planner at “PV,” the planning commission for the greater Munich area. “We want to change that.”

Martin Tönnes, chief planner of the Ruhr Cycling Highway, has a clear goal in mind: To attract tens of thousands of commuters to the new infrastructure. Some 1.8 million people live within a two-kilometer range of the Ruhr cycling route — a “huge potential for heavy use,” says Tönnes.

“Since November you can cycle the 11 kilometers between the cities of Mülheim and Essen in 31 minutes at standard speed, while you need 23 minutes by car in normal traffic, plus the time to find a parking space,” says Tönnes. He is particularly enthusiastic about the growing popularity of electric bikes, also called “pedelecs.” In Germany, more than 2 million people own pedelecs, which have the added advantage of enabling older people to move quickly on two wheels.

The Ruhr project is scheduled to be completed by 2022 and will cost 184 million Euros, about $207 million. “That may sound like a lot, but it’s nothing if you compare the cost of car infrastructure,” says Tönnes.

Not long ago in Berlin, about 70 people gathered in the hall of a local church in the city’s Neukölln quarter to talk about the need for a referendum to upgrade the city’s biking infrastructure. “I’m Anja, I’m an all-year cyclist and have been hit by a car recently,” said one woman. A man added, “I’m Kai and I want to cycle to work without fearing for my life.”

Ten Berlin cyclists died in accidents last year, and on average the city’s police register about 20 accidents involving cyclists every day. In the summer, the city’s network of narrow cycle paths, much of it built in the 1980s and 1990s, is overcrowded, with frequent conflicts between faster and slower cyclists. While car drivers cruise on wide multi-lane streets, cyclists get crammed into narrow lanes, which often aren’t well maintained and are damaged by tree roots and frost.

But that neglect may be coming to an end. In Berlin alone, cycling activity has increased by at least 40 percent over the past 10 years, to about 17 percent of all traffic, according to data collected by the city government. More and more companies have created dedicated parking spaces for cyclists and installed in-office showers so that employees can easily change from cycling gear to work attire.

Heinrich Strössenreuther, a transport expert who convened the group in the church hall, summed up the evening’s theme in one sentence: “We’re here to change this city for the better with our pro-bicycle referendum.” Since late 2015, the newly formed initiative has pursued a key goal: By June it wants to collect 20,000 signatures on a petition calling for a biking referendum. That would kick-start the legal process toward a formal vote by Berlin’s citizens in the fall of 2017 on a detailed plan to fundamentally change Berlin’s infrastructure and public space in favor of cyclists. “What we want is not radical utopia, but something that makes a big difference,” says Strössenreuther.

The ten-point manifesto developed by the initiative would, among other measures, legally oblige the city government to give priority to cyclists over cars on at least 200 kilometers of Berlin’s residential streets, to create cycling lanes along all major avenues, to reserve preferential spaces for cyclists at traffic lights and crossings, and to construct 100 kilometers of cycling highways.

Germany’s cycling revolution has only just begun — and it is not without controversy. Unswerving car drivers and some local politicians resent investments in bicycle infrastructure out of principle, as they view cyclists as a nuisance.

In Berlin, however, the new push for better cycling infrastructure has found an unlikely ally — the conservative Christian Democratic Union, or CDU, the party of Chancellor Angela Merkel. It wasn’t left-leaning or green groups that developed the first concrete plan for a major cycling highway connecting the affluent southwest of Berlin along an abandoned railway with the political center around Brandenburg Gate. It was Thomas Heilmann, Berlin’s justice minister and deputy regional leader of the CDU.

“The number of people using bicycles is steadily on the rise, and I see it as our responsibility to create a suitable infrastructure,” says Heilmann. Under his plan, charging stations for electric bicycles will be built along the highway, as will kiosks offering everything from free air pumps to spare parts, refreshments, or even showers.

If the bicycling referendum is given the green light by the city government later this year, 170,000 further signatures will be needed by March 2017 for a formal ballot to take place later that year. In order to convince a majority of Berliners to support the pro-cycling legislation, Strössenreuther said, the initiative “doesn’t want to free Berlin from cars altogether, but aim for a city that is safer and more lively for everybody.”