Each spring, hundreds of thousands of migrating waterbirds flock northward from Africa across the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas. In search of food, they alight briefly on Albania’s Buna Delta — one of the largest remaining wetlands in all of the Balkan Peninsula.

The delta is also one of the most notorious killing grounds for migrating birds in all of Europe.

“There is a marsh harrier,” declares Borut Stumberger, a hard-bitten Slovenian researcher and veterinarian, during a recent field census of dwindling bird life in the delta. He points to a lone bird gliding low over the wetlands. “It will not last seven days,” he says.

When Stumberger first started coming here in 2003, these wetlands were teeming with ducks, geese, and other waterfowl. But when I joined him and a team of ornithologists from across Europe in January for an annual winter bird count, a hilltop offering unobstructed views from the Adriatic Sea to the white-capped mountains of the Dinaric Alps revealed skies that were mostly empty.

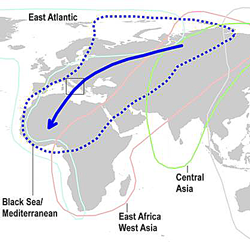

Environmental groups have estimated that more than two million ducks, geese, songbirds, and raptors are shot along the Adriatic’s eastern shores every year — part of what’s known as the Adriatic Flyway, a key migratory route for birds making their seasonal journeys between the European and African continents. A recent analysis by Wetlands International, a conservation group based in the Netherlands, concluded that as many as one-third of all birds using the Black Sea-Mediterranean Flyway — an area that includes the Adriatic Flyway — are now in decline, in large part due to illegal hunting.

Albania’s wetlands are officially protected under national and international agreements, but signs of illegal harvesting are abundant, suggesting a far different reality. Poachers hiding inside crude, limestone bunkers easily blast weary oystercatchers, spoonbills, and gargeney from the sky as they approach from the Adriatic. Other illegal hunters, packed into a crowded network of blinds within the marshes, ensure that fewer and fewer birds touch down here alive.

Reading aloud his most recent bird tallies from the Buna Delta, Stumberger ticks off a few dozen common gulls, one Mediterranean gull, and nine crows. He also counts two illegal hunting hideouts and 11 shotgun shells.

“This is not hunting,” Stumberger says. “This is massacre.”

This hasn’t always been the case, and Albania was once a haven for wildlife. For decades the country’s communist dictator, Enver Hoxha, pursued extreme isolationist policies that stifled development and all but eliminated access to the country’s forested borders and coastal wetlands. When the country opened its doors to the outside world in 1991, rampant development and exploitation of natural resources followed, including unlimited hunting of birds — primarily for sport, but also for market.

“This is not hunting,” says a European researcher. “This is massacre.”

One high-end restaurant I visited in Tirana, the nation’s capital, offered blackbird, mallard, and woodcock — the latter selling for 2000 Albanian Lek or $18 per bird.

“During the communist era, very few people owned guns and hunting was allowed only in a few resorts that were limited to the Politburo,” says Taulant Bino, Albania’s former deputy minister of the environment. “After the 90s, when the system broke down, people thought, ‘We have the right to enjoy the same freedoms that the Politburo did.’”

In recent decades, the country’s weak central government has proven unable or unwilling to enforce even the most basic hunting restrictions. In February, Albania’s newly elected government placed a two-year moratorium on all hunting nationwide. But that has done little to stall illegal poachers, whose ruthless tactics have drawn added criticism from conservationists. Hunters use decoys and play tape-recorded birdcalls to lure their prey, for example. They hunt indiscriminately in protected areas, at night when birds flock together, and during sensitive breeding and migration periods. Some use thin “mist” nets and sticky traps to catch songbirds. Others use speedboats to pursue waterbirds at sea.

“The situation in Albania is more dramatic than any other country in the region,” says Romy Durst, a biologist with EuroNatur who specializes in the Balkan wetlands. “In other countries you have big flocks of resting wildlife. In Albania there literally is no wildlife.”

Earlier this month, EuroNatur hosted a conference in Durrës, Albania, that focused on reducing the most urgent threats for migratory birds along the Adriatic Flyway. The organizers chose Albania in part because of the dire conditions facing wildlife in the country, and attendees from other parts of Europe expressed dismay at the paucity of hunting restrictions in the region.

“We were shocked to hear what sorts of birds can be hunted in certain countries, including some of the globally threatened species like the red breasted goose and ferruginous duck,” says Szabolcs Nagy, a senior advisor with the conservation group Wetlands International. “It seems to be a free playing ground for [illegal] hunters.”

When attendees of the conference took a field trip to nearby Divjakë-Karavasta National Park, hunting was apparent. “We were in the core zone of a national park in a country with a two-year hunting moratorium and you still hear shooting,” Durst says. “Law enforcement is still far from being good enough.”

Djana Bejko, Albania’s current deputy minister of environment, disagrees, insisting that the hunting ban is having an impact. “Everything is in order and the moratorium is working very effectively,” Bejko says. She notes that since the hunting ban was enacted law enforcement officials have confiscated 630 guns from illegal hunters, up from an average of only 20 per year previously.

Much of the illegal hunting in Albania has been by tourists visiting from nearby European Union nations.

When I ask about the shots heard by conference attendees, however, she concedes that some hunting does still occur. She also admits that conservationists’ complaints — that law enforcement officials in Albania are woefully underfunded — is not without merit. “For the time being we still have limited resources in terms of equipment and infrastructure provided for the rangers,” she says.

That might need to change if Albania hopes to realize its ambition to join the European Union. On June 27, the European Commission (EC) granted the country “candidate status,” but its inability to stop illegal bird killing could derail the effort.

“The European Commission is concerned about the illegal killing of wild birds in Albania,” says EC spokesman Joseph Hennon, adding that the commission “expects Albania to quickly establish the necessary legal and administrative framework required” to comply with European Union environmental regulations.

Ironically, much of the illegal hunting in Albania in recent years has been by tourists visiting from nearby European Union nations.

“As the regulations get stricter in EU countries, hunters are going to areas where hunting laws and enforcement are not as strict,” says Tibor Mikuska of the Croatian Society for Bird and Nature Protection. “For example, they go quail hunting in Albania or Romania or Serbia and try to smuggle their catch back to Italy and other Mediterranean countries where songbirds and quail are used in cuisine.”

In 2012, the last year Croatia employed specially trained wildlife inspectors at its borders, customs officials confiscated 1,300 birds from would-be smugglers. “This is not even the tip of the iceberg,” Mikuska says.

Bejko says the recent moratorium has “absolutely” stopped foreign hunters from coming into her country but, like many aspects of illegal hunting in Albania, the truth is hard to discern. At least one Albanian travel agency still offers hunting packages for foreigners on its website. For 850 euros a hunter can spend four days and five nights in Albania with an Italian-speaking guide shooting woodcock, quail, “wild duck,” snipe, and “owl,” presumably without limit.

After spending an afternoon with Stumberger in the Buna Delta of northern Albania, I joined Bino, who formerly served as Alabania’s deputy minister of environment, as he continued the bird census work south along Albania’s coastline.

Bino, 45, is widely regarded as Albania’s leading ornithologist, and he applauds the recent hunting moratorium — though he personally sought a longer, five-year ban during his time in government. He recently returned to academia, teaching environmental policy at Polis University in Tirana, the nation’s capital, and he revels in introducing students to bird watching. “The moment they see the kingfisher, they are with me, not the hunters,” he says of the brightly colored birds.

Our first stop is a brackish lagoon separated from the Adriatic by a narrow sand dune. In a steady downpour Bino quickly counts large flocks of coots, pochard, and teal, birds that bob in tight formation on storm-tossed waters. The number of waterbirds, roughly 1,100 in all, are about half of what he has typically seen in recent years.

Bino says an unusually mild winter is likely the cause for the low numbers. Many of the birds that usually come here likely stayed further north last winter. Still, having even this many birds on a small patch of water in Albania is unusual. A naval base on the far shore keeps much of the lagoon off limits to hunters. Yet where we stand, spent shotgun shells line the dirt road like paving stones.

The following day we spend an afternoon near the Greek border looking for birds amid ancient Greek and Roman ruins at Butrint National Park. Bino drives his Land Rover out on a rain-soaked mud flat until the vehicle will go no further. Parking the SUV, we walk out to a point. Across a narrow channel, the Greek island of Corfu is so close we can see individual houses along its hillsides.

After several days of near-steady rain, the clouds begin to lift. We watch, silently, as cormorants open their wings to take in the sun’s late afternoon rays. Sandwich terns plunge into the water hunting for food. A pair of spoonbills fly low overhead, their namesake bills so close I can almost touch them.

Then, a gunshot rips through the marsh.

Watch a video on illegal hunting in the Adriatic Flyway:

Video credit: EuroNatur/Gregor Aubic, WWW.EKOFILM.ORG