Size doesn’t matter.

Or at least, size is not the only thing that matters. In 21st century American democracy, massive public support is certainly desirable, especially over the long run. But what really counts with Congress is intensity.

A huge majority of Americans favor gun control, for example. According to the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago, four out of five believe a police permit should be required for the purchase of a firearm.

But a small, intense set of Second Amendment absolutists will vote against any politician who favors such an approach. In most elections, a dedicated group of 10 percent, or even 5 percent, of voters can tilt the outcome. So politicians cater to the position whose supporters are most intense — who make sure a politician aligns with them on a single issue before they even examine the rest of his record.

What does this have to do with Earth Day?

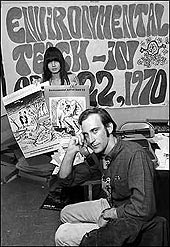

Earth Day 1970, for which I served as national coordinator, was huge. Twenty million Americans took part. Millions of Americans who didn’t know what “the environment” was in 1969 discovered in 1970 that they were environmentalists.

Moreover, Earth Day was bipartisan. Although there was some antagonism toward President Nixon among the organizers, the campaign was co-chaired by Democratic Senator Gaylord Nelson and Republican Congressman Pete McCloskey. The 1 million-person event in New York City was chaired by the progressive Republican mayor, John Lindsay.

Over the next three years, Congress passed the most far-reaching cluster of legislation since the New Deal — the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and myriad other laws that have fundamentally changed the nation. Trillions of dollars have been spent differently than they would have but for this new regulatory framework.

The conclusion the environmental movement drew from this was that it should try to grow as large as possible and to be bipartisan.

In recent decades, this hasn’t been turning out too well.

What everyone has forgotten is what happened after the first Earth Day. Just one week later, President Nixon ordered the invasion of Cambodia. The Kent State shootings followed a few days later. The spotlight shifted abruptly away from the environment.

But the environment returned to national prominence in the fall of 1970. The Earth Day organizers jumped into the Congressional elections, seeking to defeat a “Dirty Dozen” of incumbent Congressmen. The targets were selected because they had abysmal environmental records, but also because they were in tight races and were from districts with a major environmental issue that voters cared about.

The first of the seven Congressmen we took out that fall was George Fallon from Baltimore. Representative Fallon was chairman of the House Public Works Committee, the “pork” committee, and a powerful opponent of mass transit. Politicians of all stripes took notice: If Fallon was vulnerable, everyone in politics was vulnerable.

In that single primary election (won by a young upstart named Paul Sarbanes), Earth Day’s organizers had made “the environment” a voting issue.

“Earth Day is a Mississippi River phenomenon — a mile wide but only a few inches deep.

A few weeks after the election — despite the furious opposition of the coal, oil, electric utility, automobile, and steel industries — the Senate version of the 1970 Clean Air Act, authored by U.S. Sen. Edmund Muskie, passed the Senate unanimously. It was later adopted by the House on a voice vote.

Air pollution control enjoyed widespread support (much of which had been generated on Earth Day by participants in gas masks and college students burying internal combustion engines — leading to press coverage of depressing facts about air pollution on children). But what fundamentally changed the political dynamics was the intense engagement of a much smaller group of voters in the Congressional elections.

The political landscape has changed dramatically over the last 40 years, and today’s focus on bipartisanship is arguably misplaced. Republicans once counted among their leaders such thoughtful, progressive, green politicians as Nelson Rockefeller, Chuck Percy, Elliott Richardson, Ed Brooke, Bill Scranton, Jacob Javitz, John Chafee, and Mark Hatfield. Indeed, it was a Republican — Howard Baker — who drafted the most radical provision in the Clean Air Act, the “technology forcing” section that required all new cars to have catalytic converters, even though no such device was yet commercially available.

But by 1980, when Ronald Reagan carried every southern state except Georgia (Jimmy Carter’s home state), the Republican party had been transformed. President Reagan assembled the most anti-environmental cabinet in history.

Although both parties once included important mixtures of left and right, they have become increasingly polarized. In fact, the Republican leadership is now so robustly anti-environmental that the League of Conservation Voters uses affirmative action in evaluating its scorecards. A Democrat with a 60 percent voting record is seen as awful, while a Republican with 60 percent is seen as exceptional.

In this context, striving for bipartisan support produces legislation that is at best inadequate and at worst designed to fail to achieve its purpose.

The environmental movement sometimes projects a vague image about what it stands for.

I have been closely identified with Earth Day for the last 40 years, and I’m proud of helping not only to keep the event alive but of turning it into the most-widely-observed secular international holiday. Every year, Earth Day is observed in the United States in a couple of thousand cities, at least a thousand colleges, and 60,000 to 80,000 K-12 schools. It has helped to pass on environmental values to future generations, and it has consciously sought to broaden and diversify the environmental movement.

Earth Day is mostly a mainstream phenomenon, and it has played a role in focusing students on careers in environmental law, environmental health, green architecture, conservation biology, and other fields. Millions of people make choices about lifestyles, diet, housing, automobiles, and even the number of children they have because of thinking that began at an Earth Day program.

But Earth Day is, by its very nature, a Mississippi River phenomenon. It generates support that is a mile wide but only a few inches deep. There is room for environmental zealots in Earth Day — heck, most people consider me an environmental zealot. But an event seeking to enlist tens of millions of people must accept a broad common denominator. It must welcome those who are just beginning to recycle as well as those who are devoting their entire lives to the pursuit of ambitious environmental goals.

However, to succeed against the wealthy, powerful forces arrayed against it on issues like climate disruption, ocean acidification, and a global epidemic of extinction, the environmental movement also needs a large block of people who will fight for a sustainable future valiantly and without compromise. Those of us in that block may be soundly defeated — creating a context in which others may be able to negotiate acceptable compromises. But the ultimate resolution will be far better because we made our case with honesty, clarity and strength.

In recent years, the movement has sought to find soft language, novel arguments, and compromised positions that will help it raise support in new communities, including those with little or no interest in environmental values. It is on a constant lookout for spokespeople who are explicitly not environmentalists. In the process, it sometimes projects an incredibly vague image about what it stands for.

The only way Congress will act intelligently and boldly on climate change is if we give it no choice.

Today, the world faces a crisis that only a handful of experts were even vaguely aware of in 1970: climate disruption. Now, after subsequent decades of careful, worldwide, scientific study, the results are clear: We are cooking the planet.

Humanity must swiftly abandon dirty power and switch to safe, clean, decentralized, renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and geothermal. America has been trailing in these fields for the last 30 years. But America, with its superb universities, entrepreneurial culture, and venturesome capital, should lead the way.

Leading the way requires a long-term vision, programs with explicit goals and targets, and consistency of purpose. Making this transition will not be cheap, and it may involve some painful dislocations.

This won’t happen as a result of Congressional brilliance and courage. Although Congress has some brilliant, courageous individual members, as an institution it is dumb and cowardly. The only way that Congress will act intelligently and boldly on this issue is if we give it no choice.

A large block of Americans must make the climate disruption issue an initial voting screen. If a candidate is ok on climate, then we will look at the rest of her record. To move this issue forward, our voices must be as loud as those hollering for the right to carry a Colt into Starbucks or for saving Granny from death panels.

This year, Earth Day organizers are demanding a fair, comprehensive, and effective climate solution. Regional, state, local, and individual policies and actions are already underway. But a sweeping federal law is needed to show the world that America is serious. Such a law is needed to show the coal and oil and electric-utility industries that America is serious.

Politicians who try to ignore climate disruption need to start losing their jobs next November.

Most experts I know agree, in private, that the Cantwell-Collins bill in the Senate is the best climate legislation that has yet been proposed. In fact, it is the only option under consideration that would make a meaningful dent in greenhouse gas emissions in the near term. It places an absolute cap on carbon where it enters the economy; auctions 100 percent of carbon permits; and returns the revenues to the public on a pro rata basis. Moreover, it’s just 40 pages long, while the competing bills contain another thousand pages of loopholes, special interest exceptions, and bad baggage.

But the so-called eco-pragmatists have one powerful argument against it. They say it can’t be passed. A prominent green leader told me, “To pass any climate bill at all, we have to appease coal-state Democrats, shovel as much money as necessary to pro-nuclear Republicans, and buy off the electric utilities.” That is an apt description of the Kerry-Lieberman-Graham bill now making the rounds in the Senate.

This sentiment has been broadly, if reluctantly, embraced by most of the large, mainstream national environmental groups working on climate as well as by the Obama Administration.

But it appalls virtually every environmentalist who lives outside the beltway.

The environmental movement has spent more than a billion dollars trying to pass a cap-and-trade bill, and it is feeling some desperation. The people who contributed all that money expect some results. The pressure to pass something — almost anything — that arguably puts some sort of cap on carbon is intense.

Yet every draft of the climate bill is weaker than its predecessor. Every draft does a poorer job of putting a reasonable price on carbon. Every draft is larded with more taxpayers dollars for socialized, centralized nuclear power and for “clean coal.” Every draft carries more sweeteners for the utility industry, the automobile industry, the coal and oil industries, and the industrial farmers and foresters.

Instead of weakening the bill, we need to change the politics.

Politicians who try to ignore climate disruption — and that’s a whole lot of them — need to start losing their jobs next November.

The junk-science, climate-denying interest groups are rich, powerful, and ruthless. But they are mostly the same bunch that fought tooth-and-nail against the Clean Air Act four decades ago. They will lose now for the same reason they lost back then: They favor 19th century answers to 21st century problems.

Earth Day will continue its “big tent” approach to environmentalism, providing a welcome to everyone who authentically cares about environmental values. But while that is an appropriate outreach strategy for an event designed to broaden and educate the movement, it is not a strategy that will prevail politically over fierce opponents, egged on by bloviating talk radio hosts and fact-free blogs.

We will not win a climate bill that is worthy of the name, a bill that will deal honestly with the full enormity of the threat we are facing, until there exists an intense environmental voting bloc that will subordinate all other issues to climate. That block needs to construct a successful campaign to return some Congressional villains to private life—perhaps even a couple of dozen.

We must make it crystal clear to politicians everywhere that we are serious. This issue to too vital and too urgent to do any less.