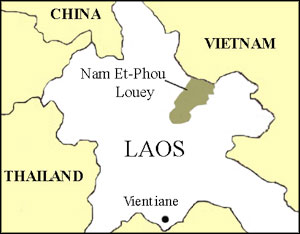

Deep in the rugged mountains of Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area on the Laos—Vietnam border, Laotian game wardens came upon the following scene: pieces of the pelt of a recently killed tiger, its bones removed, with rifle shells scattered in the trampled vegetation.

The wardens knew precisely what had happened. Poachers had trapped a tiger in a baited snare that had encircled one of its front feet with a cable and lifted the animal into the air. Coming upon the snarling tiger, the poachers had shot it, then proceeded to carve out its 22 to 26 pounds of bones, which — when ground up — would be sold to middlemen for the Chinese medicinal market. The poachers then cut off the tiger’s penis, which would eventually be soaked in wine and the wine drunk as an aphrodisiac.

Middlemen paid the poachers up to $15,000 for the bones and other parts of the tiger, an astronomical sum in a country where per capita income is around $400 a year. In China today, the remains of a tiger may fetch $70,000, with the ground bones highly valued as a cure for rheumatism, according to Arlyne Johnson, co-director of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Laos Program, which is trying to stem the flow of the illegal wildlife trade.

Twenty-five years ago, hundreds of tigers roamed large swaths of relatively untouched jungle in Laos. But in recent years — particularly in the last decade — development, deforestation, and a booming traffic in wildlife have reduced Laos’s tiger population to 50 or fewer individuals, according to Johnson and other scientists. The main driver of the rapid depletion of tigers and scores of other species of birds, animals, and reptiles is the growing affluence of neighboring Thailand, Vietnam, and especially China, where a vast new market for wildlife products has arisen.

Nothing symbolizes this market more vividly than the so-called “north-south economic corridor,” a recently completed road that now connects once-sleepy Laos — and its timber and other raw materials — to China. With its booming economy, China is also the world’s largest — and fastest-growing — market for wildlife.

Laos is the latest front in the struggle to rein in an underground global trade that every year kills tens of millions of wild birds, mammals, and reptiles to supply multi-billion dollar markets around the world. The U.S. and Europe rank among the largest buyers of elephant ivory and tiger parts and also feed this illicit business with their demand for exotic pets.

But as I learned on a trip to Laos earlier this year, it is the Asian market — particularly in China — that powers this trade. A major source of demand is traditional Chinese medicine, which is based on the belief that the parts of certain animals have curative properties — river otter tails for labor pains, bear bile for fever, shark fins for cancer. This trade is taking a heavy toll on wildlife not just in Laos, but around the world — in Southeast Asia, the Russian Far East, Africa, and even North America.

The reasons for the rise of commercial hunting and trapping are not complex — rapid development and growing affluence that create demand; an increase in international trade; the emergence of increasingly sophisticated smuggling networks; an influx of weapons and technology; and easier access to wilderness areas because of road building by extractive industries. All drive overexploitation of wildlife, but addressing the trade in a manner that is effective but also fair to local people is a huge challenge.

Once ruled by the Pathet Lao communist government, Laos remained largely isolated from the outside world. But socialism was gradually replaced with a more market-oriented economy and in 1986 the government launched an economic liberalization program that opened the way for a trickle of investment that has recently become a flood. Like other forest-dependent people, rural Lao long relied on hunting to supplement their rice-dominated diet with protein. But the opening of the economy put a price on the heads of virtually all animals, ranging from river insects to tigers. This, combined with an abundance of weapons from years of war and insurgency, gave hunters the incentive and the tools to convert Laos’ rich biodiversity into cash. Now the very resources upon which rural people have long depended are at risk.

The opening of the Laotian economy put a price on the heads of virtually all animals, ranging from river insects to tigers.

The situation is particularly grim along the recently completed north-south economic corridor — an 1,150-mile road that runs from Bangkok, Thailand to Kunming, China, passing through the heart of Laos. The corridor has spurred widespread deforestation and wildlife poaching. Vast tracts of forest along the corridor have been logged for timber and converted for teak or rubber plantations, while hillsides have been burned for sticky rice cultivation. The money comes from Chinese business owners who not only provide finance, but sell snares and traps and place orders for fresh wildlife, guaranteeing a market for hunters and smugglers.

The situation deteriorated to such an extent that in 2005 the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) scaled back its project in Nam Ha National Protected Area, the second-largest nature reserve in the country at the time. Wildlife is commonly sold along the corridor, especially near the Chinese border. But other than dead animals in markets, I saw little evidence of animals and birds along the corridor — or, for that matter, in most of Laos.

In eastern Laos, the Vietnamese are the main financiers of new roads intended to facilitate access to Laos’ resources; wildlife comes as a bonus. In Laos, like other countries, there is a strong synergism between road building and the wildlife trade. Loggers supplement their income with hunting and use logging trucks to transport bushmeat to traders and urban markets.

Extractive industries like logging and mining also actively encourage human settlement, boosting demand for game as a source of protein. Cash-rich workers can afford to buy weapons, snares, headlamps, and outboard motors to speed wildlife depletion, especially in regions where arms are widely available. A study, soon to be published in the journal Conservation Letters, found pervasiveness of firearms to be a key contributing factor to Laos’ precipitous drop in wildlife.

For poachers, the tiger is the crown jewel. But tigers in Laos and other countries also face a secondary threat — depletion of prey populations from unsustainable hunting, making it difficult for tigers to survive in what would otherwise be suitable habitat and pushing them into conflict with humans. Hunters are using livestock to bait tigers; the loss of a cow is a small price to pay for catching a big cat. Sometimes a cow or a pig is slaughtered, dragged into the forest, and wired with snares or explosives so that a tiger lured by an easy meal is quickly converted into a pharmacological product.

Pangolins — scaly anteaters believed to cure blood circulation problems and skin conditions — are also highly prized. While commercial international trade in pangolins is banned under CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), pangolins have been extinguished from much of Laos by poachers. The extent of the pangolin trade in Southeast Asia remains enormous. TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade-monitoring network, recently estimated that at least 100,000 pangolins — mostly from Malaysia and Indonesia — are killed each year to meet Chinese demand.

More than 25 tons of pangolin parts have been seized in Vietnam in the last year alone, but the enforcement action demonstrated one of the major challenges facing those working to control the trade. Instead of destroying the pangolins, the Vietnamese government auctioned off the contraband, thus allowing the wildlife products to ultimately reach their intended destination. “Selling off the seized pangolins sent out entirely the wrong message,” said Sulma Warne, TRAFFIC’s Greater Mekong program coordinator.

In many parts of Southeast Asia, depletion of rare species has only increased their value, encouraging hunting down to every last individual in some cases.

Mixed signals from the government are not unusual. Reports from the Environmental Investigation Agency, TRAFFIC, and the Wildlife Alliance have cited complicity of authorities across Southeast Asia in the wildlife trade. Cross-border trade of large volumes of wildlife necessitates collaboration between traffickers and officials. Border agents in Laos and Thailand are known to impose a “tax” on wildlife products, regardless of their origin or legality. Those who run the trade tend to be influential, often with ties to corrupt government officials or the military, and don’t limit themselves to wildlife; investigations have turned up links to other illicit trade, including weapons, drugs, and people.

Some charged with carrying out the law act with impunity; forest rangers sometimes cite access to fresh meat as a chief benefit of a field assignment, according to Sarinda Singh, a University of Queensland researcher who conducted an assessment of wildlife trade in Laos.

In many parts of Southeast Asia, depletion of rare species has only increased their value, encouraging hunting down to every last individual in some cases. The result: Many areas now suffer from “empty forest syndrome,” where wildlife densities are too low to support people or predators like tigers.

Addressing the wildlife trade means attacking on two fronts: supply and demand. Reducing demand for wildlife products in consuming countries is a critical component to this effort. “Wildlife trade won’t end until people stop buying,” said Troy Hansel, who works in wildlife trade monitoring for the WCS in Laos.

The supply side is more complex. Trade restrictions eliminate a source of income for the rural poor. So in Laos WCS is taking a multi-pronged approach to dealing with the wildlife trade. In addition to working with the government to clarify laws and strengthen enforcement through training of wildlife authorities and customs agents, WCS has established a comprehensive program in local communities to explain which animals can be legally hunted and emphasize the consequences of wildlife depletion. The program includes registration of firearms, an informant network funded through collection of fines, and a system of forest stations from which rangers launch patrols into protected areas.

Still, beyond enforcement and education, WCS’s Johnson and Hansel believe it is critical to prove to the Lao people that wildlife is valuable as a living entity. The conservationists are planning to launch a small ecotourism project to help create a strong link between wildlife protection and well being of locals around Nam Et-Phou Louey. To date, WCS’s efforts seem to be paying off. In parts of Nam Et-Phou Louey where it has conducted its outreach project and has a strong presence, WCS sees changes in wildlife behavior that indicate less hunting pressure, including more birds in villages and wildlife along rivers.

A short foray into the park showed hopeful signs. During a single evening boat trip in Nam Et-Phou Louey, I spotted owls, civets, a pair of otters, and an East Asian porcupine. The day before, rangers even came across tiger tracks.

“Lots of good habitat remains,” said Johnson. “The recovery of wildlife populations is possible with proper management.”