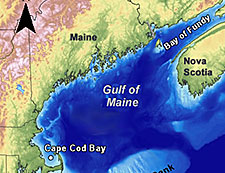

Every summer and fall, endangered North Atlantic right whales congregate in the Bay of Fundy between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to gorge on zooplankton. Researchers have documented the annual feast since 1980, and well over 100 whales typically attend, a significant portion of the entire species. Only this year, they didn’t. Just a dozen right whales trickled in — a record low in the New England Aquarium’s 34-year-old monitoring program. And that comes on the heels of two other low-turnout years, 2010 and 2012.

Numbers of the critically endangered marine mammal have been ticking up in recent years just past 500 individuals, so no one thinks the low turnout in the Bay of Fundy augurs a decline in the species as a whole. The right whales must have gone elsewhere. But where? And more importantly, why?

“Our whales have been missing in their normal habitat areas, where we’ve learned to expect them over three and a half decades,” says Moira Brown, a senior scientist at the aquarium who runs the monitoring program. “It’s quite shocking when you go out there day after day after day and you don’t see any right whales.”

It’s clear to scientists that the whales’ new itinerary must signal a shifting food supply.

This change in North Atlantic right whale behavior is occurring against a backdrop of major climate-related ecosystem shifts taking place throughout the northwest Atlantic Ocean. While Brown and other right whale researchers are not ready to attribute changes in the species’ feeding or migratory patterns to any one factor, including global warming, what is clear to them is that the right whales’ new itinerary must signal a shifting food supply. A zooplankton species called Calanus finmarchicus is the whales’ mainstay. Researchers reported an unusual scarcity of the zooplankton in the Bay of Fundy this summer. By the same token, in Cape Cod Bay, where right whales have been unusually plentiful, other scientists have been documenting increasing concentrations — so much so that the normally invisible creatures noticeably color the water.

Other ecosystem shifts are afoot in the northwest Atlantic off the eastern coasts of the United States and Canada. Sea surface temperatures in waters such as the Gulf of Maine are rising and various marine species, including cod and red hake, are shifting their ranges northward, according to recent studies. Increasing precipitation, the rapid disappearance of Arctic sea ice, and the melting of ice sheets in Greenland and Canada are all expected to pour more freshwater into the northwest Atlantic, causing increased stratification of ocean waters and changes in the abundance and distribution of phytoplankton and zooplankton at the bottom of the food chain, studies show.

The missing right whales are a nagging mystery to marine biologists and were the hot topic at an annual meeting of right-whale cognoscenti this month in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Once numbering in the many thousands, North Atlantic right whales are among the rarest animals on earth, haunted by the specter of extinction after centuries of whaling. Right whales were protected under whaling conventions enacted in 1935 and 1949, but today accidental collisions with ships and entanglement in fishing gear pose grave threats.

As curious as where the right whales aren’t is where they are.

As curious as where the right whales aren’t is where they are. Brown’s team spotted a reasonable number on their other late-summer feeding ground, which lies southeast of Nova Scotia — but not the ones they expected. Instead of what Brown calls “wise old whales” typical of the area, they found juveniles and a mother-calf pair more characteristic of the Bay of Fundy. She also received credible reports of right whales far north of their usual summer feeding grounds, where they’d never been reported: two animals this summer near Cape Breton on Nova Scotia, and two last summer off northern Newfoundland.

But the real trove of right whales has been in Cape Cod Bay in winter. Whales have always stopped there to feed en masse, but the last four winters the numbers have skyrocketed, according to Charles “Stormy” Mayo, director of a program at the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies that has been monitoring right whales in the bay since 1984. “Shockingly, we’ve had on average approximately half of the population of the North Atlantic Ocean in our bay,” and possibly as much as three-quarters, Mayo says. “This is really kind of Right Whale Kingdom.”

Not only are more right whales stopping in than ever, but they are gathering up to three months earlier — late November or early December as opposed to February. They’re also coming for more than just the buffet now, as they’ve been spotted mating between meals. Another first, according to Mayo: Last January a calf was born in Cape Cod Bay. Previously all known births occurred off the coast of Georgia or Florida, 1,200 miles south.

Dramatic though all the changes are among right whales, Brown and Mayo say it’s hard to know what to make of them. Both are quick to point out that even their teams’ painstaking, long-term efforts to document the right whales’ comings and goings only give them a small window on the animals’ lives. Brown says her lost whales could well have been feeding contentedly at some remote zooplankton hotspot they’ve always visited, unbeknownst to people.

The cause of the shift of the right whales’ favorite prey, C. finmarchicus, is uncertain. Topping the list of suspects is climate change-driven warming in the Gulf of Maine. In 2012, the gulf was at the epicenter of an immense oceanic heat wave stretching from Cape Hatteras to Iceland, which resulted from a confluence of climate change and an unusually warm year, according to Andrew Pershing, a biological oceanographer with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute and the University of Maine. Gulf water temperatures reached 5 Fahrenheit degrees warmer than average, approaching conditions not expected until the century’s end.

Right whales and their prey aren’t the only species on the move in the region.

The warm waters could be producing fewer or less-nutritious C. finmarchicus, or shifting the currents that carry them, according to Mark Baumgartner, a marine ecologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. With the heat wave dissipating, Baumgartner says he’s hopeful right whales will soon return to the Bay of Fundy. In the long run, however, he says their disappearance could be a harbinger of things to come. In the Gulf of Maine, C. finmarchicus is at the southern edge of its range, and Baumgartner and Pershing note that global warming may drive the zooplankton northward for good. If so, right whales and numerous other marine animals that depend on C. finmarchicus will likely follow, revolutionizing the gulf’s ecosystem.

Right whales and their prey aren’t the only species on the move in the region. “Really what we’re seeing is a food-chain shift right up from plankton through fish into marine mammals and birds,” Brown says. For the past few years her team has been spotting sperm whales in the Bay of Fundy, where they’d only seen a single one since 1980. In the next water body north, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, researchers rarely spotted more than a handful of endangered fin and humpback whales a day this summer, down from several dozen in years past, according to Richard Sears, founder of the Mingan Island Cetacean Study, which has been surveying whales there since 1979. The few that came arrived a month or so later than usual and gathered in uncustomary areas, while throngs of whales seemed to linger outside the bay. Sears has heard reliable reports of humpbacks visiting Baffin Island recently, far to the north of their usual stomping grounds. He says the reasons behind his team’s unusual observations are unclear, though they undoubtedly relate to the whales’ krill and fish diet.

Other examples include puffins nesting weeks later than usual and having trouble fledging their young, possibly due to changing fish supplies. Leatherback sea turtles are heading south through Cape Cod waters two months later than in autumns past, and in greater numbers. More than 50 have been snarled in fishing gear so far this fall, up from an average of five or six, says Scott Landry, director of the whale rescue program at the Provincetown Center for Coastal Studies. Cod, lobsters, and northern shrimp — current or recent pillars of the Gulf of Maine’s fishing industry — seem to be decamping into cooler northern waters, even as southern species like black sea bass and longfin squid move in.

Scientists note that as warming continues, marine ecosystems may be thrown badly out of whack.

Many of the shifts are consistent with climate change-induced warming, Pershing says. Other scientists note that as warming continues, marine ecosystems such as the Northwest Atlantic may be thrown badly out of whack. With the temperature and salinity of the ocean changing, and with spring arriving earlier and fall later, the timing and location of phytoplankton blooms and zooplankton abundance will also likely shift, throwing off the timing of feeding, migration, and reproduction of many species.

The right whales’ calving season starts soon off the coasts of Florida and Georgia. If the calves are plentiful and the adults look healthy, experts will feel better about their summertime meanderings, Brown says. Meanwhile, she and her team are planning what to do if the right whales are missing again next summer in the Bay of Fundy.

They have already started reaching out to fishermen and other mariners for help spotting whales further afield. A new version of an app put out by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to help mariners steer clear of right whales will let them easily report sightings. And Baumgartner recently led development of autonomous underwater gliders that record, identify, and report back calls of right, fin, humpback, and sei whales, all endangered species. Brown would love to turn these gliders loose in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which she suspects may hold unidentified right whale habitat and could become a refuge if Fundy overheats. Scientists are even bandying about the idea of outfitting C. finmarchicus-eating seabirds with transmitters to see if the birds might lead them to the right whales.

“Something has changed,” Brown says. “The animals are responding to it. We’re trailing along behind trying to find where they went.”