The Dinaric Mountains of southeastern Europe are home to three of the continent’s largest carnivores – the Eurasian brown bear, the Eurasian wolf, and the Eurasian lynx. They roam widely through woodlands of ash, oak, beech, and pine that run the length of the range from Greece to the Alps. The jagged cliffs and sheer-sided canyons, cut by some of the last free-flowing rivers on the continent, offer near-ideal habitat for these animals.

This Balkan region, already threatened by the construction of highways and dams, is now being carved into increasingly constricted and less hospitable chunks by a new threat: border fencing. In the summer of 2015, as a flood of refugees from the Middle East and Africa streamed into Europe, Hungary closed its border. That left Slovenia as the main refugee conduit into Western Europe. Alarmed at the massive tide of migrants, Slovenia began building a razor-wire security fence along its 670-kilometer (416-mile) border with Croatia, giving little if any consideration of the environmental impacts on the wildlife.

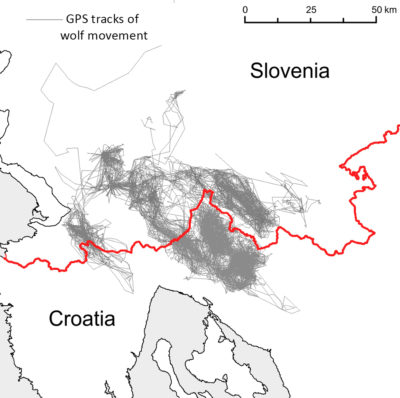

Those effects are now being felt by the region’s migratory wild animals. The Croatian-Slovenian border area is currently home to scores of bears that, according to DNA testing and satellite tracking, have long roamed freely between the two countries and beyond. Of the 10 or 11 wolf packs found in Slovenia, five traditionally have regularly moved across the Slovenian-Croatian boundary where the fence is now being erected. The threatened lynx also counts as homeland this area that was for centuries a borderless frontier of valleys, hills, and farmland.

On his most recent trip into the mountains along the Slovenian-Croatian border, biologist Djuro Huber counted 11 dead roe deer, all caught up in the fencing. The deer stumble into the barriers while foraging. In a desperate bid to escape, they drive themselves further into the razor wire, entangling themselves and eventually dying of blood loss. “Certainly many more died, but the border officials try to remove them before [they are] photographed,” says Huber of the University of Zagreb in Croatia. “But it is what we don’t see that troubles me the most.”

While the deer are the most obvious victims, carnivores tend to simply turn away from the fences. If a young male bear or a wolf can’t cross the border to mate, for example, he will look for a more accessible female. The result is genetic isolation and inbreeding, a problem already threatening the region’s dwindling lynx population. This can lead to an increase in diseases and unwanted genetic mutations that may ultimately lead to localized extinctions, scientists say.

GPS tracking data shows the movement of wolves between Slovenia and Croatia before border fencing was erected in recent years. The red line represents the pathway of new razor wire security fencing built to deter refugees from entering Slovenia. Linnell et al, 2016

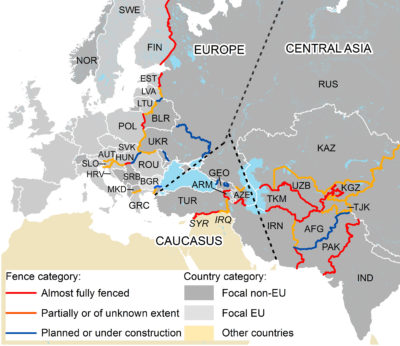

In the past year or so, hundreds of miles of razor wire-topped barriers have been erected across southeastern Europe in an effort to halt the movement of refugees escaping wars and poverty in Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Africa. Even as the migration crisis has eased this year, fences continue to go up. Not only do the fences kill wildlife and lead to genetic isolation, according to a June 2016 study published in the journal PLOS Biology, but these barriers also hamper the efforts of organizations such as the European Wilderness Society (EWS), which is working to protect and expand existing wilderness throughout Europe. According to EWS Chairman Max Rossberg, Eastern Europe holds some of the best-preserved wildlands on the continent and some of its healthiest wildlife populations.

The impact of border fences on wildlife is not limited to Europe. A 2011 study pointed out that the fence along the U.S.-Mexico border blocks 16 key species from about 75 percent of their habitat. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has said that a fence proposed by President-elect Donald Trump would impact 111 endangered species and 108 migratory birds. In Asia, nearly the entire 2,900-mile Chinese-Mongolian border is fenced, impacting species such as the Asiatic wild ass and the Mongolian gazelle. Border fences also have been erected between states of the former Soviet Union.

Given that freedom of movement for people has been a core principle of the European Union, the new Balkan fences are meant to be temporary. However, conservationists fear they may become permanent additions to the landscape. For many European scientists, this marks a major setback; Huber says the fences are the biggest threat to protecting wildlife he’s seen since he started researching Europe’s bears 35 years ago. “I don’t know how we stop this,” he says.

The fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989 and the opening of borders across Europe gave an impetus to the idea of wildlife and ecosystem conservation on a continental scale. Within months of the dissolution of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, scientists and environmentalists began discussing such initiatives, leading in 2003 to the creation of the European Green Belt Initiative. It envisioned an ecological network, spanning 24 nations, that would connect national parks, biosphere reserves, and trans-boundary protected areas across Eurasia. The EU Habitats Directive, adopted in 1992, formalized guidelines for trans-boundary cooperation. These efforts have paid off, as the PLOS Biology study notes: “In part due to the harmonization of legislation across borders and restored connectivity, Europe has witnessed a tremendous recovery of its large carnivore and herbivore populations in recent decades.”

To continue with this success, conservationists have looked east to the former Warsaw Pact nations, seeking to connect them with other conservation efforts already underway. Thanks to historic management practices, as well as generally positive cultural attitudes towards carnivores, the Balkans, as well as Ukraine farther to the east, are reservoirs of relatively healthy wildlife populations. Those populations could benefit conservation and reintroduction efforts in Western Europe. This is particularly true with carnivores such as the wolf and bear. One Eurasian brown bear, dubbed Ivo, was tracked by satellite collar as he roamed for 21 months from Slovakia, to Hungary, to Poland, to Ukraine, crossing international borders 63 times.

“This part of Europe is extremely important due to native populations of carnivores,” says Vlado Vancura of the European Wilderness Society. From the Balkans, he says, these carnivores have a tendency to push north into Italy, Austria, and then on to points west, repopulating previously abandoned areas and injecting valuable genetic diversity into Western European ecosystems.

A map showing fences along national borders in Europe and in Asia as of June 2016. Linnell et al 2016

But such movements are threatened by the growing number of razor-wire fences. “European nations are small,” says Aleksandra Majic, a biologist at the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia. “They are not large enough to host their own healthy populations of large carnivores.”

Although the flow of refugees has slowed, the fences are still being built. Few if any refugees traveled in the Dinaric Mountains, but a fence is nevertheless being erected in this rugged territory. Huber, Majic, and other conservationists say politicians in the Balkans are building the fences to divert attention from other economic and political problems. “They [the fences] only make sense when viewed within the context of populist politicians playing the ‘fear’ card to fuel nationalism and to try and appear to be doing something,” said John Linnell of the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research in Trondheim, Norway and the lead author of the PLOS Biology study.

He and others note that many of the fences may in fact be illegal. While international law does not forbid the construction of border fences, a wide range of other binding international agreements are being violated by the fencing, the PLOS Biology study found. These include European Union laws calling for environmental impact studies before fences are erected. The barriers also appear to violate tenets of the Bern Convention, as well as of the Habitats Directive, which lays out a rigorous process that EU member states must follow before embarking on a project that may impact protected landscapes and species. For so-called “priority species” such as the wolf and bear, nations must obtain the approval of the European Commission before proceeding with projects that will impact those animal populations.

The PLOS Biology paper notes that if the Slovenian government makes good on its vow to build a fence along its entire border with Croatia, wildlife managers in both countries will likely be forced to take measures to protect large carnivores. Bears can be legally hunted in both countries, but the size of the cull may have to be reduced if the fence is not taken down, the paper said. Wolves can be legally culled in Slovenia — “a practice that may have been defendable before construction of the fence, but which will need to be reconsidered in the future,” the paper said. As for dwindling populations of the Dinaric lynx, “the razor-wire fence may just be the last push for the population to spiral down the extinction vortex,” according to the paper.

In Slovenia, the main association representing the hunting community reports finding about 50 red deer killed in the fences. Majic says that sources on the Croatian side report much higher numbers of dead deer. But there were “no recorded mortalities of large carnivores, although bear fur was found in the fence,” she says.

One silver lining to the spate of fence building is that it has spurred greater cooperation among European conservationists and scientists.

In 2017, Majic will participate in an EU-funded project to coordinate bear management across Italy, Austria, Slovenia, and Croatia. Huber and the Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe recently authored a letter to Brussels pushing for removal of the fences. Next year, they plan to push the European Union to protect bears, wolves, and lynx at a continental scale, not on a national level. Meanwhile, the European Wilderness Society is co-sponsoring the creation of a cross-border program for protected areas in Poland, Belarus, and Ukraine. The PLOS Biology study also calls for an assessment of how much fencing now exists and where it is located.

Yet the path forward is unclear. Political volatility in Turkey and a lack of resolution to the conflicts in Iraq and Syria have Europe on edge. A fence is currently being built along the Bulgarian-Turkish border that will cut through a key wildlife corridor. Along the border between Russia and Finland, a barrier is planned that could harm bears, wolves, lynx, wolverines, and forest reindeer.

European conservationists hope to see the fences removed before they cause any permanent harm to Europe’s wildlife. In lieu of that, there is a push to design wildlife-friendly fencing and conduct environmental impact studies before any more barriers are constructed. The PLOS Biology paper noted that sections of a fence between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have been retrofitted to allow saiga antelope to pass. In some rugged Balkan areas that are not used by refugees, fences would not need to be constructed. In other areas, such as along common wildlife migration routes, fences could be replaced with electronic monitoring technology, the PLOS Biology paper said.

“The big problem,” concluded the University of Zagreb’s Huber, “is that from Mongolia to the United States to Europe, building fences and walls — that’s a trend.”