Yale Environment 360: How did you first become interested in microplastics?

Richard Thompson: I was conducting experiments on the shore that were accumulating lots of little pieces of plastic. I mobilized the students, and we organized beach cleans. I started asking the question, “What are the smallest pieces?” My students went out on the beach, and they brought back samples of sand. When we looked at them with a microscope, we saw pieces that didn’t look like sand, that turned out to be plastic. We discovered that microplastics, including many smaller than the diameter of a human hair, contaminated waters around the U.K.

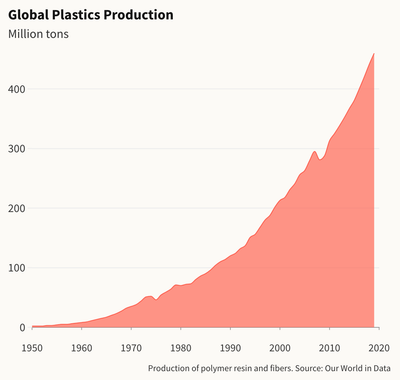

In a 2004 paper published in Science, we showed that they were biologically available to a range of marine organisms. We also showed, using archived samples, that the abundance of these small fragments, which we named microplastics, had increased significantly since the 1960s.

e360: We’ve known about plastic pollution for a long time. Why did it take so long for scientists to look into this question of microplastics?

Thompson: There were some studies of plastic pollution in the 1960s and 70s. But nobody was recording small bits. And it wasn’t until our 2004 paper that this really started to attract attention. I suppose it was kind of out of sight, out of mind, particularly for what I was describing, which was truly microscopic. You wouldn’t have been able to see it without a microscope.

e360: Did you immediately sense how important a discovery was?

Thompson: Probably not. I mean, I thought it was important enough to submit to Science. When I got back from holiday [after the paper was published,] my computer was full of media inquiries. Almost nothing else that morning. The phone was ringing constantly.

“The predictions are that we’ll see wide-scale ecological harm from the microplastics in the next 70 to 100 years.”

Since then, we’ve looked from Mount Everest down to the deep sea, from the poles to the equator. We’ve found this material everywhere. I recently came back from a major scientific conference [MICRO 2024 in Lanzarote, Spain] just about microplastics. I would never have dreamt of that 20 years ago. There were 700 scientists from all around the world registered at the conference just to discuss microplastics. So interest has grown phenomenally.

e360: In your latest paper, you cite polls that show that people rate plastic pollution as a more pressing issue for the oceans than climate change. How do you account for that?

Thompson: The [microplastics] problem is going to be irreversible. And the predictions are that we’ll see wide-scale ecological harm from microplastics in the next 70 to 100 years. We’ve already got clear evidence of ecological harm. They’re not going to degrade, they’re persistent contaminants. And because of their small size, it’s going to be kind of irreversible. So I don’t know, have the public got that level of concern right or wrong?

Climate change is a major issue that we need to grapple with. I’d argue that maybe tackling the problem of plastic pollution, although incredibly complex is, I’m hesitant to say, simpler. I would argue that a lot of the societal benefits that we get from plastics could be realized without the harm by starting to use plastics more sustainably. We’ve failed to design plastics [for recycling and reuse] for example. So that’s part of the problem with producing colossal quantities, well over 400 million tons of plastic every year, 40 percent of it is destined for single use.

e360: There are a lot of different sources of these microplastics. Do we know what the main ones are?

Thompson: The biggest source overall accounting for about two-thirds of all microplastics is the larger items of litter that are accumulating in the environment. The packets, the bottles, all of those things will fragment over time into smaller and smaller pieces. There are also fragments and fibers that wear away from larger items like car tires and clothing. The other third is direct emissions of small pieces to the environment. For example, the small bits of plastic that are intentionally added to products such as cosmetics and paints.

e360: You are a marine biologist. A lot of attention has been paid to the question of microplastics ending up in the ocean. After 7,000-plus studies, what do we now know about the impact on the ocean ecosystem?

Thompson: Well, it’s clear that microplastics are incredibly biologically available to a wide range of creatures. I think well over 1,000 species have been shown to ingest them. And there’s clear evidence of harm to individuals. There are also experiments that demonstrate effects on communities and also on ecosystem services, things like gas exchange between sediment and seawater. So we’re seeing evidence of harm across all levels of biological organization, from cellular to ecosystem.

“We can’t wait for all these studies [on plastics and human health] to be done before we take action.’

e360: I’ve read that microplastics have been found even in plankton and algae. Is there any evidence that, as with heavy metals like mercury, they accumulate as they go higher up in the food chain?

Thompson: Good question. No, there’s not. There’s evidence of transfer along food chain, but there isn’t biomagnifcation as we see with mercury, for example, from the best evidence that we’ve got at the moment. Now, where I think we may see a change to that is as we start to work on smaller and smaller particles.

e360: Are these very tiny particles even more dangerous than the larger ones which, when they are ingested, generally just pass through the digestive system and get excreted out?

Thompson: The scientific consensus is yes, they are, because they’re not only going to go into the gut, they’re going to pass into the circulatory system. The gut handles foreign material from time to time. It’s a barrier in its own right. But once we’re inside the circulatory system in organisms, then I’d say the potential is quite different. So I think small is certainly more biologically available.

Plastic pollution in the Buriganga River in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Munir Uz Zaman / AFP via Getty Images

e360: There have been reports that say that the quantities of plastics entering the environment far exceed the quantities we’re actually finding in the environment. Where are these missing plastics as they call them?

Thompson: Yeah, this question of the missing plastics, it’s interesting. Back in 2004 when I published that first paper, I entitled it “Lost At Sea: Where Is All The Plastic?” Because what I did not see at that time in any of the data that was coming from beach cleans was the increase in abundance that you might expect to see. And neither did I see it from surface trawl data. But the reason I believe is that we weren’t yet recording the small bits, so we were missing a fraction. And also there are sinks, places of accumulation that we’re not yet looking at. The deep sea looks like it’s got a lot in it, but we don’t have all that much data from it.

e360: So potentially, just like we have the Pacific garbage patch, there could also be places where these microplastics are accumulating in the ocean?

Thompson: Yes, that’s right. There are surface gyres, but I think the deep sea is also really quite a big sink. We’ve got some data there to illustrate quite high concentrations, indeed concentrations higher than in sediments close to some cities. The deep sea is downhill from everywhere, if you like.

e360: Microplastics are also found on land and in the air. I understand that their level in indoor air is often extremely high. Is that right?

Thompson: Yes, a key source is fibers from textiles, and that’s our clothing, It’s carpets. It’s curtaining. When three similar items of clothing were tested, we got up to an 80 percent difference in the rate of release. So it’s clear there are interventions that could be made at the design stage to really reduce this microfiber shedding.

“There’s a whole range of plastic items that actually we could live without, and I think we’re going to need to.”

e360: Where do microplastics show up in the human body? Do we find them in the blood, in the organs?

Thompson: In our latest paper, there are 20-odd different references to accumulation in the human body that we point to. Do we have the science budgets to spend billions further drilling down into human health? Have we got two decades to pursue that? I mean, we don’t know when the strongest evidence around human health might emerge. It could be tomorrow. It could be 20 years. It might cost billions. We can’t wait for all these studies to be done before we take action. If we’ve already decided it’s harmful, wouldn’t it be better to invest those limited science budgets in exploring where microplastics are and how to eliminate them?

e360: What do we need to do to begin to solve this problem?

Thompson: I call them the three R’s — reduce, reuse, recycle. So we need to start with primary polymer reduction. There’s a whole range of plastic items that actually we could live without, and I think we’re going to need to. It includes single-use plastic bags given away at checkouts. it includes single-use cups. It includes microbeads in cosmetics, We need to make sure the products we’re making are essential to society.

e360: What about the reuse and recycle?

Thompson: Increasing the use of reusable containers could be a key strategy here. To date, very little has been designed with recycling in mind. Recycling rates globally are less than 10 percent. If product design and waste management had gotten together decades ago, we would be in a stronger place now. We’re also going to need transparency of labeling to ensure that chemicals of concern are listed. And we need to simplify [the composition of] chemicals in plastics to make them safer and to make them of more circular [reusable] materials.

e360: This would require regulations on a global scale. Is the world ready for that?

Thompson: We’re going to need a science body attached to the U.N. treaty to help to guide us through all of that in a way that’s independent of conflicts of interests.

It’s very different to the discussions that we had with industry over tobacco smoking, for example, where it was clear there was no safe way to smoke. Nobody’s saying there’s no safe way to use plastics. It’s just that we need to start making them to be safer and more sustainable than we have done so far. And that’s what the treaty needs to help us do. And it’s a frustration to me. We could be in a much stronger place if industry had maybe embraced that voluntarily a bit earlier.

The global plastics pollution treaty is a vehicle to getting us there. The next step, of course, is the negotiations in Busan in November, and the challenge is going to be getting all of the nations to agree on that treaty.

“I would hope the major [companies] deliver their products in packaging compatible with the local waste management system.”

e360: That’s the plastic treaty negotiation in South Korea in November. So what kind of outcome would you like to see come from that meeting?

Thompson: Well, we need to see an agreement. And at the moment, there’s a lot of disagreement. And that’s understandable because like anything, there’s going to be winners and losers, so people are going to disagree. Since, the primary carbon source for plastics is petroleum, the major fossil oil and gas producers also see a concern for them. And, of course, some countries might want to strike some things out of the treaty that could be in my view be really important. So we’re going to have to hope that this lands in the right place. So far, it’s been frustrating to see the lack of consensus among nations about how to address this global problem.

e360: What can we do as individuals?

Thompson: Of course, you can try to refuse single-use items. You can try to take a reusable bag with you. You can try to take a refillable coffee cup. You can do what you can to make plastic items last and use them as long as possible.

Beyond that, we’re really going to need better design. I mean, if we look to a supermarket of the future, say in 10 years’ time, I would hope that the major brands, producers, and retailers deliver their products in packaging that is compatible with the local waste management system. We need to create clothing that sheds less particles, fishing gear and agricultural plastics that are safer. That’s where the real responsibility lies. It’s not about consumers having to agonize over minute labels on products that have been poorly designed. I’d like that responsibility to be lifted from the consumer.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.