Nobody loves electrical power transmission lines. They typically bulldoze across the countryside like a clearcut, 150 feet wide and scores or hundreds of miles long, in a straight line that defies everything we know about nature. They’re commonly criticized for fragmenting forests and other natural habitats and for causing collisions and electrocutions for some birds. Power lines also have raised the specter, in the minds of anxious neighbors, of illnesses induced by electromagnetic fields.

So it’s a little startling to hear wildlife biologists proposing that properly managed transmission lines, and even natural gas and oil pipeline rights-of-way, could be the last best hope for many birds, pollinators, and other species that are otherwise dramatically declining.

The open, scrubby habitat under some transmission lines is already the best place to hunt for wild bees, says Sam Droege of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, and that potential habitat will inevitably become more important as the United States becomes more urbanized. He thinks utility rights-of-way — currently adding up in the U.S. to about nine million acres for power transmission lines, and another 12 million for pipelines — could eventually serve as a network of conservation reserves roughly one third the area of the national park system.

Some utilities are letting things grow to form a scrubby habitat of wildflowers, ferns, and low shrubs.

Remarkably, some power companies agree. Three utilities — New York Power Authority, Arizona Public Service, and Vermont Electric Power Company — have already completed a certification program from the Right of Way Stewardship Council, a new group established to set standards for right-of-way management, with the aim of encouraging low-growth vegetation and thus, incidentally, promoting native wildlife. Three more utilities, all from Western states, are currently seeking certification.

“Whether the other few hundred will be similarly interested, we don’t know. We hope they’ll see the value,” said Jeffrey Howe, the council’s president. The gist of the program is straightforward: Federal regulations currently require power companies to keep their transmission line corridors free of large trees and other tall vegetation. Beyond that, though, there is nothing to require the common practice of routinely mowing everything down to grass, or broadcast-spraying herbicides. So instead, some utilities have shifted to spot-spraying herbicides on unwanted plants, and letting everything else grow in to form a scrubby habitat of wildflowers, sedges, ferns, and low shrubs. It’s called Integrated Vegetation Management, or IVM.

Australian utilities have already expressed interest in the program, as have pipeline companies, said Howe. The Brazilian utility CEMIG is also independently testing a similar management style at a pilot site in the Atlantic coastal forest and another in dry upland forest. Power line corridors in Europe generally run across industrialized farmland meaning utilities there have so far seen little potential to manage them as habitat.

In the United States, said Howe, traditionally risk-averse utility executives “don’t want to spend money on something until they know, first, that it’s going to be valued in the world and, second, that they’re doing the right thing.” One aim of developing the new vegetation-friendly standards now is to reassure them on both points. The standards may also “affect how things are regulated five or ten years down the road,” he said.

Even for companies that have pioneered the IVM idea, wildlife habitat wasn’t the idea. “We kind of backed into this,” said Anthony W. Johnson, III, who manages 2,500 miles of transmission corridors in New England for Northeast Utilities. “We really haven’t managed for wildlife. We manage to prevent certain vegetation from encroaching. We try to keep some things out, and in doing this, we wind up encouraging native low-growth.” Native wildlife was a happy side effect.

Corridors enable individual populations of a species to connect with one another.

“The frosted elfin butterfly is a globally imperiled species, and in southern New England, most of the occurrences are under power lines,” said University of Connecticut entomologist David Wagner. Likewise, “the Karner blue butterfly is drop-dead gorgeous, and a poster child of the conservation movement, and at least in the eastern part of its range, its existence is dependent entirely on power lines.” In one IVM transmission line, Wagner recently re-discovered a wild bee species, Epeoloides pilosula, which had not been seen in the U.S. since 1960.

“The transmission lines are probably critically important for a lot of these early successional species,” said Robert Askins, a Connecticut College ornithologist. That’s partly because the heavy reforestation of New England over the past century has eliminated most other open habitat, and partly because the rights-of-way are permanent. They’re also corridors, and even networks of corridors, which means individual populations of a species can connect with one another instead of becoming genetically isolated. In studies by Askins in Connecticut, power line corridors provide habitat for now scarce birds like the brown thrasher and the yellow-breasted chat (a state endangered species).

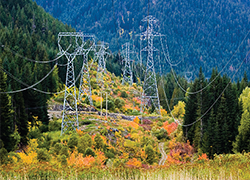

Against all odds, IVM power line corridors are sometimes also beautiful. Kimberly N. Russell, an ecologist at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, describes one site she studied, near Lookout Point Lake in Oregon, as a sort of garden spot. “You’re surrounded by evergreen closed-canopy forest and then there’s this explosion of color, this linear streak of color, and it’s all wildflowers.”

That’s not something anyone would say about utilities’ traditional management methods. In Columbia, Maryland, for instance, Baltimore Gas & Electric (BG&E) went into an area it hadn’t been able to maintain for several wet years and cut down everything, inadvertently enraging local residents. The ensuing conversation resulted in a pilot IVM project there, and it now includes walking trails and informational signs about plants and wildlife. The company is also starting to implement IVM elsewhere in its system, said William Rees, a BG&E vegetation manager. “It’s taking a little bit of a leap of faith, but early indications are that it is cost effective, on an operational basis.” As the scrub vegetation grows in, it excludes many taller trees, he said, and somewhere between three and seven years after abandoning mowing and broadcast spraying, “costs drop dramatically.”

If it saves money (and provides public relations bonus points), why don’t more utilities manage their power lines this way? “One of the stumbling blocks they face is that they have long-term contracts with mowers,” said Russell, “and these are old school relationships. So there’s lots of pushback.” In addition, some communities are uncomfortable with herbicide use, though IVM proponents say it’s far safer and used in much smaller amounts than in the past.

Utilities get resistance from their own foresters because the new approach is more work.

Utilities also get resistance from their own foresters, said Rick Johnstone, a former power company manger who is now an IVM consultant, “because it’s more work to manage.” Conventional methods allow a forester to “sit in the office and say it’s 2014, it’s time to mow that line. But when you get into IVM, you need to look at it, you need to do the assessment, and determine what’s the best practice. What’s the vegetation growing there? What’s the density of vegetation? Are you near water? And that takes more expertise.”

Federal rules are also an impediment. Interference from trees and unpruned foliage did not cause the widespread 2003 power blackout in the U.S. Northeast, but they made it worse. Under rules that were subsequently revamped to ensure reliability of the grid, utilities that fail to control vegetation now face fines by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation of up to $1 million a day.

That’s “had a huge effect on the way some utilities manage their systems,” said John Goodrich-Mahoney of the Electric Power Research Institute. “Some utilities became more aggressive in removing all vegetation from the transmission corridor, and also clearing right to the edge of the right-of-way.” Some even worked with landowners beyond the right of way to remove trees that might potentially cause fall-ins. But “that very aggressive response is now starting to swing back to a middle ground, where companies are more comfortable having some vegetation.”

Northeast Utilities manager Anthony Johnson cautioned that conservationists need to be realistic about what power line corridors can do for wildlife. Seeding a right-of-way with milkweed for monarch butterflies, for instance, may sound like a natural, but it will work only where it already grows naturally. “It’s much easier selectively removing what you don’t want than to try to put in things that you do.”

On the other hand, when biologists came to him a few years ago and pointed out that scrub oak is an essential habitat for at least 15 regionally threatened moth and butterfly species, it wasn’t a close call. “It turns out that it has significant value to the frosted elfin butterfly,” said Johnson, a consideration that other, more traditional utility managers might not be comfortable even saying out loud.

“Now instead of spraying it, we cut it when it gets to be about eight feet in height.” Does that entail an extra cost to the power company? “Not at all,” he said. “Zero.”