The clang of garbage cans will still probably wake people way too early in the morning. But in Santa Rosa, California, at least, the roaring diesel engine will be quiet, replaced by a silent, electric motor.

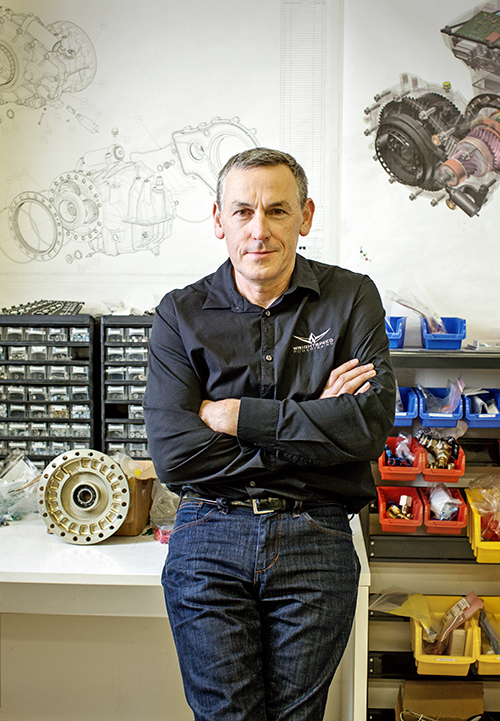

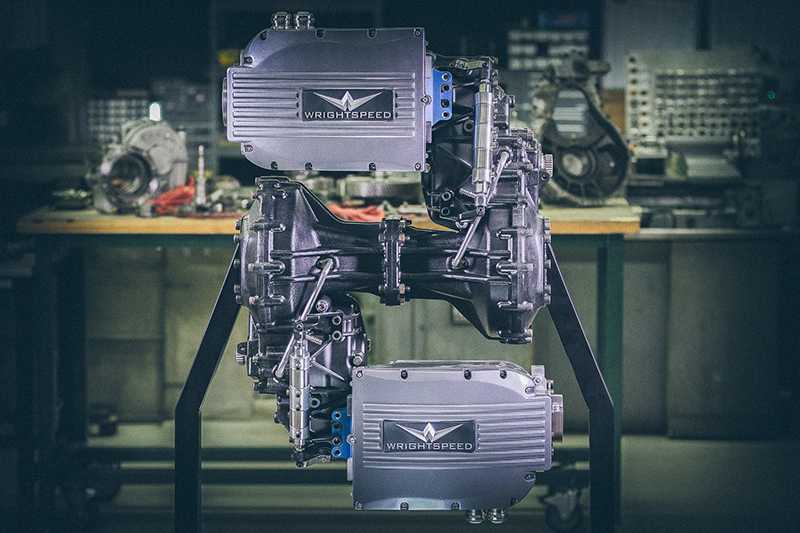

The electric garbage trucks scheduled to begin rolling there this summer may be less alluring than the sporty vehicles that engineer Ian Wright helped design as co-founder of Tesla Motors. But Wright, who left the high-end electric car company to start Wrightspeed, maker of electric powertrains for medium- and heavy-duty commercial vehicles, is on a campaign to force large, carbon-belching engines off the road.

“The dream right now is to completely eliminate the nasty, smelly, noisy diesel engines from garbage trucks in five years,” Wright says.

In today’s hyperkinetic world, moving people and things is the planet’s fastest-growing energy-based source of greenhouse gases, with some projections saying that transport emissions could nearly double by mid-century as developing nations industrialize. Climate scientists and policymakers say replacing petroleum-burning engines with alternatives like electric motors is critical to meeting the greenhouse gas-reduction goals set by the international community in Paris last December.

But while the adoption of electric cars has been hindered by high prices, limited range, a lack of charging stations, and competition from cheap gasoline, heavier-duty models are undergoing rapid innovation for applications like battery-powered city buses, delivery trucks, freight loaders, and ferries. Experts say that these electric workhorses can play an important role in decarbonizing transport, and could spin off technologies that benefit electric cars, a far larger — and, from a carbon perspective, more important — market.

Christopher Knittel, director of the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, says the development of heavier-duty electric motors, batteries, and vehicle technologies could potentially help cut commercial and municipal transport’s carbon emissions by 25 to 50 percent in the coming decades.

These new motors could spin off technologies that benefit electric cars, a far larger market.

The industrial sector may be quicker than personal car buyers to adopt pricey new technologies because costs can be amortized and benefits such as fuel savings will multiply across equipment fleets, says Peter Harrop, chairman of the tech market analysis firm IDTechEx. Commercial and industrial electric vehicle sales will outpace the consumer market at least until the middle of the next decade, according to Harrop.

Moreover, the new technologies being developed for heavier-duty applications could also potentially boost range and performance for electric cars.

“We are driving down the component costs, and driving up the system efficiencies, and we have a very cost-effective architecture,” says Wright. “And that all helps get it into lighter vehicles.”

Electrically propelled commercial conveyances are nothing new. Small, battery-powered trucks like forklifts have toiled inside warehouses for decades. Electric cables or rails have long powered trams and trains.

But the emergence of industrial-strength electric battery and motor technology is freeing public transit from route-restricting wires and enabling trucks to haul weightier loads over longer distances. Analysts say that the greatest emissions impact outside the personal vehicle market will probably come from electrifying public transit. Large, battery-powered city buses can now travel their entire daily route (generally up to around 150 miles) on a single charge. China, the world leader in manufacture and export of electric buses, is also the biggest electric-bus user, with around 80,000 currently on the road and thousands more set to come. Shanghai alone announced plans to add 1,400 electric buses a year beginning in 2015.

Electric buses are also gaining ground in the United States and Europe. Dozens are already rolling in places such as Southern California’s San Gabriel Valley, Nashville, and San Antonio, and several cities are considering adding more than 200 additional electric buses nationwide over the next few years. Even London’s iconic double-deckers are going electric, with the first five being put into service this spring. IDTechEx projects that global electric bus sales will near 60,000 in 2017, and top 250,000 by 2025.

The new electric drives are particularly suited to medium- and heavy-duty vehicles that make frequent stops, and they are gaining use in short-haul cargo trucks, tractor-tractors, and delivery vans, including more than 800 electric trucks now being used by FedEx and UPS. The technology is even making its way to sea, including hybrid electric tugboats escorting freighters in the port of Los Angeles, and all-electric ferries that have just started plying the Norwegian fjords.

As a means of limiting global warming, however, electrifying commercial transport can’t compensate for the lag in the consumer market, analysts say. Light-duty passenger cars and trucks produce the bulk of carbon dioxide output from transportation today — around 60 percent in the U.S. — and ambitious climate goals, such as the Obama administration’s plan to get 1 million electric cars on U.S. roads by the end of last year, have been coming up short.

Electric garbage trucks can more than double mileage and reduce emissions up to 68 percent.

About 1.3 million electric cars are on roads worldwide today, and with the current deluge of cheap gasoline, sales of new electric cars actually fell in 2015.

Still, the medium- and heavy-duty commercial rolling stock responsible for roughly a quarter of transportation emissions presents a significant target for cutting greenhouse gases.

Wright’s California-based company is targeting stop-and-go trucks in classes 4 to 8, weighing from around 7 tons to more than 15 tons. Electric powertrains outperform standard engines in delivering high torque at low speeds, which best suits the work demands on these types of vehicles.

Wrightspeed has developed a range-extended electric powertrain with regenerative braking on all drive wheels so the frequent hard stops made by vehicles like garbage trucks keep the batteries charged. While the system also includes a range-extending generator that still requires fuel, the electric powertrain — installed as a retrofit to a standard diesel garbage truck — more than doubles the mileage and reduces emissions up to 68 percent.

“We do garbage trucks because a single truck burns 14,000 gallons a year,” says Wright. The company is also producing electric delivery trucks for FedEx, and has had inquiries for a variety of other applications, including mining trucks, trains, and coastal patrol boats.

He acknowledges that the overall climate benefits are limited by the fairly small niche markets for vehicles like garbage trucks. “On an individual basis, it makes enormous amounts of sense,” says Wright. “However, there are only 150,000 garbage trucks in the country.” Still, Wright says he expects that 90 percent of those will use electric drives within five years.

New designs for industrial motors are overcoming the lack of horsepower that irks many electric car drivers today. Colorado-based UQM Technologies recently developed an electric motor with lighter materials and a new process for controlling the internal magnets that make it rotate — boosting power enough to haul a loaded bus up a steep hill, according to the company’s vice-president of engineering, Josh Ley. The company makes motors for the U.S. electric bus maker Proterra, as well as “beyond-road” applications such as tugboats, yachts, and even a record-setting electric racing airplane.

Marine transport is one of the areas that’s “electrifying at a startling pace,” says Harrop. Huge container ships, for instance, can use side-pointing electric propellers to dock, and electric motors power a variety of pleasure boats.

Marine transport an area that is “electrifying at a startling pace,” says one executive.

Electric motors currently can’t produce the sustained power needed by the global fleet of nearly 50,000 large shipping vessels while at sea, but they can provide many smaller fuel-saving gains in port.

“Increasingly, what was not electric is starting to become electric,” says Harrop, whose firm estimates the electric marine market, now valued at $500 million to $1 billion, will grow to $34 billion within 10 years.

But despite this fast-paced technical evolution, the near-term outlook for electric transportation is as mixed for commercial vehicles as it is for cars. Range limits, lengthy charging downtime, and hefty batteries make electric drives impractical for long-distance transport like aircraft, big rig tractor-trailers, and cargo ships. Although it’s cheaper to drive on electricity than gasoline mile-per-mile, the high price of batteries continues to make electric vehicles considerably more expensive than conventional vehicles. Increasing production could lower manufacturing costs, but could also drive battery prices up if growing demand creates shortages of essential battery ingredients like lithium salts.

And then there is the crucial issue of whether the electricity is being produced by fossil fuels or renewable energy sources, such as solar and wind power. Overall, the electric grid is growing greener, according to latest International Energy Agency report, which states that around 90 percent of new electricity production in 2015 came from renewable energy sources. Even China has cut its coal use by more than 10 percent since 2011. Still, nearly 70 percent of that country’s electricity is produced from coal. So, while electric vehicles generally have significantly lower emissions than conventional vehicles in places with relatively clean grids, like much of Europe, that is not the case in areas still generating electricity primarily from coal, like China, India, and Australia.

“If we’re going to decarbonize the transit system through electrification,” says James Sallee, a transportation economist at the University of California-Berkeley, “then you’re going to have to figure out how to clean up the electric grid substantially.”

Even with these choke points, analysts say, electric transportation still holds promise for reining in greenhouse emissions, and humble vehicles like garbage trucks could help lead the way.

“The best way to get carbon out of the transportation system as a whole would be to get these sorts of slivers out of light duty, medium duty, heavy duty, rail and so on,” says Knittel. “There’s no silver bullet here, but there’s a bunch of silver pellets.”