The fires that blazed in Indonesia’s rainforests in 1982 and 1983 came as a shock. The logging industry had embarked on a decades-long pillaging of the country’s woodlands, opening up the canopy and drying out the carbon-rich peat soils. Preceded by an unusually long El Niño-related dry season, the forest fires lasted for months, sending vast clouds of smoke across Southeast Asia.

Fifteen years later, in 1997 and 1998, a record El Niño year coincided with continued massive land-use changes in Indonesia, including the wholesale draining of peatlands to plant oil palm and wood pulp plantations. Large areas of Borneo and Sumatra burned, and again Southeast Asians choked on Indonesian smoke.

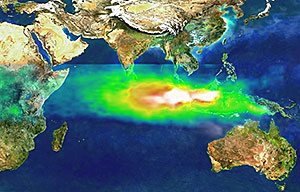

In the ensuing years, Indonesia’s peat and forest fires have become an annual summer occurrence. But this summer and fall, a huge number of conflagrations have broken out as a strong El Niño has led to dry conditions, and deforestation has continued to soar in Indonesia. Over the past several months, roughly 120,000 fires have burned, eliciting sharp protests from Singapore and other nations fed up with breathing the noxious haze from Indonesian blazes.

The pall of smoke still drifting over Southeast Asia is the most visible manifestation of decades of disastrous policies in Indonesia’s corrupt forestry and palm oil sectors. Indonesia’s runaway deforestation and draining of peatlands has become a matter of serious concern not only to its neighbors, but also to the global community. In recent years, the country’s land-use changes have made Indonesia the world’s sixth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, and this year’s fires are likely to propel the country into the top five, behind China, the United States, the European Union, and India. On some days last month, carbon emissions from Indonesia’s peat and forest fires equaled the daily emissions of the entire U.S. economy.

Despite efforts by conservation groups and some international companies to reduce the plundering of forests, Indonesia’s deforestation rate increased by 30 percent from 2013 to 2014. As late as the 1960s, about 80 percent of Indonesia was forested; by 2013, less than half of the country’s original forest cover remained. Indonesia surpassed Brazil as the country with the largest rate of deforestation in 2012, when it lost 2 million acres of primary forest.

The smoke drifting over Southeast Asia is a visible manifestation of decades of disastrous policies in Indonesia.

A key question now for climate campaigners and forestry conservation groups is whether the reaction to Indonesia’s current haze crisis will be harnessed to enact effective reforms, or will simply go to waste. Pressure is mounting on Indonesia to make a long-term dent in this fire cycle, and the issue is likely to be discussed at the upcoming United Nations climate negotiations in Paris in December. Late last month, as he prepared to visit the United States, Indonesian President Joko Widodo reiterated his support for an absolute moratorium on new licenses to develop peatlands. That moratorium has been in place since 2011 and has heightened attention to egregious cases, but has not been comprehensively monitored.

He said that while the government undertakes a review of existing licenses, license holders would be prohibited from opening up any peatlands that have not yet been drained and planted. Palm oil companies with significant land banks of undisturbed peatlands will not be allowed to convert them to agriculture, saving an up to 7 million acres. President Widodo also instructed his minster of the environment and forests to initiate a program to re-wet disturbed peatlands.

“If implemented, these measures will stop the bleeding,” says Frances Seymour, the former director general of the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) in Indonesia and now senior fellow at the Center for Global Development.

Jim Leape of the Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford University says that the catastrophic fires and recent White House meeting between President Widodo and President Obama could prove to be a catalyst for change. Leape says that the palm oil sector can continue to expand — without destroying forests — by intensifying production on already-degraded lands.

“The largest palm oil companies in Indonesia are committed to that task,” says Leape. “You have many leading civil society groups poised to support such a shift. You have international partners poised to support such a shift.”

Widodo’s announcement is a bold step, but it remains to be seen if his decrees will be enacted. The forestry ministry is widely seen as corrupt. Questions remain about whether Widodo has the authority to invalidate licenses that have already been issued. But these legal debates may take a back seat to action because the fires have created an intense health and economic crisis.

Seymour says there is reason for optimism. “Following through on this agenda would be consistent with President Widodo’s professed desires to prevent a recurrence of the public health emergency caused by the fires, to weed out corruption, and to support indigenous rights,” says Seymour. “This time, the stars could be aligned for a land-use paradigm shift.”

Analysts say that this year’s devastating fires could be a turning point for Indonesians fed up with forest degradation.

Seymour says there is also much work to be done on the international level to drive home the global value of protecting Indonesia’s forests and peatlands.

The Paris climate negotiations could help devise solutions to Indonesia’s deforestation crisis, as experts discuss what policies and independent monitoring tools could be employed. One potential model is Brazil, which has dramatically reduced its high deforestation rate through heightened law enforcement and government policies that encourage development of previously degraded lands, says Seymour.

In both Brazil and Indonesia, non-governmental organizations such as Greenpeace have successfully persuaded international corporations such as McDonald’s to stop buying palm oil, soybeans, or other agricultural products grown on deforested land. In Brazil, the environmental community was given a major boost when the country hosted the first Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Seymour says the summit shone a spotlight on forest and environmental issues and helped nurture a community of civil society organizations, economists, and scientists who developed tools, such as satellite monitoring, to slow deforestation.

“Brazilian policy makers have seen that the conservation and restoration of tropical forests is not only good for the environment, but also for quality of life, the economy, and foreign relations,” says Solange Filoso, a research assistant professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. She is working with Brazilian researchers to monitor reforestation to reverse the loss biodiversity and assist in the recovery of ecosystems services — work that could be applied to other developing countries with tropical forests.

Indonesia lags quite a few years behind Brazil in the democratic process. But President Widodo’s recent announcement of an end to further peatland conversion indicates that conservation groups and activists are gaining greater influence. “I think it is fair to say that Indonesia is in certain ways following Brazil’s example, but with Indonesia’s own special features,” says Seymour.

She and other analysts say that this year’s disastrous fires could be a turning point for Indonesians fed up with forest degradation. More than a half-million people have sought medical help for acute respiratory illness. Air quality in cities in Sumatra and Kalimantan has measured around 2000 on the Pollution Standard Index; a reading of 300 is considered hazardous. Six provinces have declared a state of emergency. Some residents have been evacuated onto ships to escape the smoke. At least 19 people have died since July 1, and thousands of premature deaths will likely result from extended exposure to the smoke, public health experts say.

The haze has closed schools, grounded flights, and angered key Indonesian trading partners such as Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. Economic losses from damage to agriculture, forest degradation, health, transportation, and tourism are estimated at $14 billion to $30 billion. The burning typically stops when seasonal rains arrive in October. Rain has fallen in Kalimantan and doused some of the fires, but strong El Niño conditions have delayed the autumn rains, which some experts predict may not arrive until December or early 2016. In addition, the drained peat lands in many areas are 15 meters deep — they smolder unabated when burned, much like underground coal mine fires.