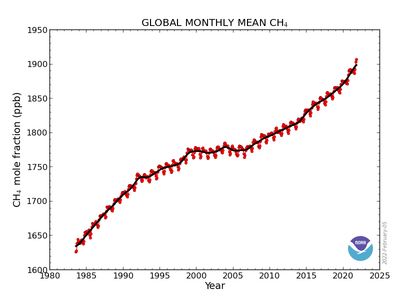

Global methane concentrations. NOAA

Last year, atmospheric methane levels reached a grim new milestone, surpassing 1,900 parts per billion, the highest level in almost 40 years of record-keeping, according to new data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Concentrations of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, have been trending upward for more than a decade, with 2020 seeing the biggest one-year jump on record. Humans are producing the bulk of methane pollution by raising livestock, filling landfills, and drilling for oil and gas, research shows, but it’s not clear what is causing the spike in emissions.

“The causes of the methane trends have indeed proved rather enigmatic,” Alex Turner, an atmospheric chemist at the University of Washington, told Nature. Recent research has yet to provide a clear answer, Turner said.

Some scientists have speculated that the growth has been caused by the expansion of the oil and gas drilling, as methane is prone to leak from wells and pipelines, while others have suggested that methane-producing microbes in wetlands, landfills, and newly thawing permafrost are driving the emissions rise.

More than 100 countries have pledged to cut methane emissions by 30 percent by 2030, a goal that scientists say is crucial for limiting warming in the short-term, giving humanity more time to adapt to rising temperatures. But the way that countries gauge the impact of methane may be undermining efforts to curb emissions, according to a new study.

Methane stays in atmosphere for only about a decade, as opposed to centuries as carbon dioxide does, but in that span it traps about 80 times as much heat. But rather than evaluate the impact of methane in the short term, international negotiators tend to measure its impact over a century. On that scale, methane is only 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide. This method of accounting is distorting climate policy, leading countries to de-prioritize methane cuts, the study suggests.

“Perhaps countries with huge dairy and agricultural industries would prefer to downplay methane and use a 100-year timeframe,” said Sam Abernathy, a PhD candidate at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences and lead author of the study. “Using a shorter time horizon, such as 24 years, would alter the magnitudes of commitments already made by valuing methane reductions significantly more.”

ALSO ON YALE E360

In Push to Find Methane Leaks, Satellites Gear Up for the Hunt