Botanist Li-Bing Zhang has spent years collecting ferns in the caves and limestone formations of southwestern China and neighboring Southeast Asia. When I met him recently in a Vietnamese national park, his research vehicle, a silver van, was bursting with fern specimens. Zhang and two colleagues had found them in tropical forests and at the entrances of 10 caves.

About 10 of the specimens, including a cave fern that his team had found in Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park in central Vietnam, were probably unknown to science, Zhang said. He planned to test his hunches when he returned to his laboratory at the Missouri Botanical Garden, where he works as an associate curator. “The problem is that a lot of species go extinct unnoticed,” Zhang told me while trekking through a forest in jeans and rubber boots. “That’s why we do our collecting.”

Limestone formations in Southeast Asia, or karsts, which spread across a belt of non-contiguous land nearly the size of California, contain fragile and biodiverse environments. The caves’ dark, humid passages play host to dozens of species of ferns, bats, insects, spiders, mites, blind fish, and many other plants and invertebrates.

But these limestone karst landscapes, and the caves that dot them, face growing threats. As tourism expands in response to demand from a growing Asian middle class, caves across Southeast Asia and nearby Chinese provinces are being developed as scenic attractions. In October, for example, officials in central Vietnam announced that a local company planned to build a $212 million cable car in Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park, where Zhang recently collected ferns in limestone caves. The cable car would ferry tourists to the world-famous Son Doong cave.

A thriving construction industry in Southeast Asia is driving demand for limestone.

A thriving construction industry in Southeast Asia is also driving demand for limestone, sometimes from quarries in concession areas that contain caves. In a prominent example, a Swiss cement company’s subsidiary is quarrying limestone in Hon Chong, an outcropping of hills and caves in southern Vietnam that is an internationally recognized hotspot of invertebrate biodiversity. In November, in a preliminary summary of a survey of the site, a team of seven scientists reported that years of quarrying had “caused the extinction of a number of species.” The cement company, Holcim Vietnam, has said it is helping to supply badly needed raw materials for Vietnam’s booming construction industry, and is working with scientists to offset its environmental impacts.

“To produce cement, we need to quarry — that’s a fact,” Nguyen Cong Minh Bao, sustainability director for Holcim Vietnam, said in a telephone interview. “But on the other hand, we know our impact, so that’s why we work with all the institutions to see how we can conserve the species.”

Much like a mountaintop or a remote island, a tropical cave offers a unique blend of light, moisture, and soil that only suits certain types of plants or organisms. And because cave-dwelling plants and animals are highly sensitive to even small changes in light or moisture, the practice of clearing nearby land for agriculture or other purposes can have significant impacts on them, even if a cave is not directly targeted.

No scientist has quantified the full threat to Asia’s caves, but a widely cited 2006 study in the journal BioScience estimated that companies in Southeast Asia quarry 178 million metric tons of limestone per year — roughly the amount of construction and demolition waste generated annually in the United States. Limestone quarrying is “the primary threat to the survival of karst-associated species, and it will certainly exacerbate the biodiversity crisis in Southeast Asia,” the study said. It added that the annual increases in the region’s limestone quarrying rate — then about 5.7 percent — exceeded the rate in all other tropical regions, including Africa and Latin America.

‘Are we really only interested in the furry or the feathery, and perhaps a few scaleys?’ asks one scientist.

In interviews, scientists painted a bleak picture of threats to cave biodiversity throughout Southeast Asia and in China’s southwestern provinces. For example, Menno Schilthuizen, a professor of evolution and biodiversity at the Netherlands’ Leiden University who studies cave snails in Malaysia and Borneo, said that there are “very few” caves in all of western Malaysia that haven’t suffered from quarrying and other human activities.

And Alex Monro, a senior botanist at Britain’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, who has conducted research in southwestern China, said many Chinese caves have been disturbed by tourism, medicinal plant collection, burials, and people or cattle seeking shelter. Aside from occasional tourism infrastructure, in the form of trails or gates, he added, “management of caves is not in evidence on the ground.”

Not all of the world’s caves lack management plans. Bermuda, for example, has regulations that were specifically designed to protect caves and their inhabitants. And some caves — in Croatia, Slovenia, and the United States, for example — are partially open to the public but otherwise protected.

But caves in China and Southeast Asia have typically been a low conservation priority. Scientists say one barrier to better protection is that the plight of cave-dwelling organisms — many of which are difficult or impossible for humans to see — rarely attracts the attention of governments or influential conservation groups.

“These things are there, they are threatened, and they are going, and yet there is no one really giving them the time of day,” says Tony Whitten, regional director for Asia-Pacific at the conservation group Fauna & Flora International and co-chairman of the Cave Invertebrate Specialist Group at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). That raises a moral question, Whitten adds: “Are we really only interested in the furry or the feathery, and perhaps a few scaleys? Is there any value to species conservation per se, or is it only certain subsets that we’re concerned about?”

Limestone caves and formations provide a number of ecological and economic benefits. They operate as filters for watersheds and provide groundwater for irrigation and human consumption. Cave-dwelling bats control pests and produce guano, which is used as a fertilizer. They also help to pollinate durian trees, a fruit-bearing cash crop grown in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. At least 40 percent of the region’s bats use caves as roosting sites, primarily because they are large, stable microclimates, reports the Southeast Asian Bat Conservation Research Unit.

Scientists say that Southeast Asia’s tropical limestone environments represent a global hotspot of cave biodiversity.

There are several theories about why some plants and animals live in caves. One is that some surface-dwelling organisms move underground when environmental conditions undergo dramatic change — for example, after glaciers retreat or advance. Other theories propose that the distribution of some species is restricted to caves as a result of deforestation, livestock grazing, the introduction of invasive species, and other human-driven activities.

For example, scientists recently discovered at least eight species of arthropods living in caves on Easter Island in the South Pacific, according to an August study in the journal BioScience led by Jut Wynne of Northern Arizona University. The study suggested that the arthropods—which account for nearly a third of the island’s known endemic species— are no longer able to survive in surface environments after years of overgrazing, the introduction of invasive species, and other land-use changes.

Scientists say that Southeast Asia’s tropical limestone environments represent a global hotspot of cave biodiversity. “In terms of the number of species that are limited to caves in the tropics, certainly Southeast Asia is by far the richest,” says David Culver, a professor of environmental science at American University and co-editor of the Encyclopedia of Caves.

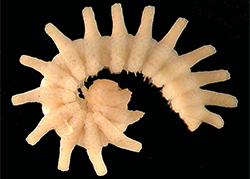

In one example, scientists in Malaysia found that 6 percent of the invertebrates they collected — in just three hours — were probably new to science, according to a 2005 study in Malayan Nature Journal. And in a 2009 study in Botanical Studies, Li-Bing Zhang and a colleague from Chongqing Normal University reported that several species of the fern genus Polystichum were native to just a handful of caves in southwest China.

Because species in Asian limestone are isolated, ‘you get a lot of endemism,’ says an expert.

One reason for this remarkably high biodiversity is that tropical Asian caves tend to be smaller, and farther away from each other, than are caves on other continents. “Flora and fauna in Asian limestone are isolated, and because they’re isolated you get a lot of endemism,” says Schilthuizen of Leiden University. “It drives home the point of how evolution works.”

But for the same reason, human activity can pose especially great risks to the plants and animals that live inside. In southern Vietnam, for example, the small limestone outcropping in Hon Chong is 30 miles from the nearest outcropping. Partly as a result, scientists say, many of the invertebrates living in its caves and hills are endemic to that spot — and vulnerable to even small disturbances.

Holcim Vietnam has funded surveys of invertebrate fauna near its Hon Chong limestone quarries. Most recently, it paid for a group of seven independent geologists and invertebrate specialists to survey the site for two weeks in October. Provincial officials, working with the company and the IUCN, are now weighing a proposal to designate some of the site as a nature reserve. Bao, Holcim Vietnam’s sustainability director, said the reserve could help mitigate the ecological damage caused by the quarries.

But scientists who know the site well question whether the company has done enough to protect invertebrates. “Holcim supports the IUCN action plan for protecting the remaining hills and funded our last trip,” Louis Deharveng, a biologist at the Museum of Natural History in Paris who has been studying Hon Chong for decades, said in an email. But there is no indication, he added, “that they would keep out of quarrying even the smallest piece of karst.”

ALSO FROM YALE e360The Rise of Rubber Takes Toll On Forests of Southwest China

Farther north, in central Vietnam, a plan for a cable car through Phong Nha-Ke Bang National Park appears to be moving ahead. Duong Bich Hanh, an official in UNESCO’S Vietnam office, says the IUCN has asked the country’s UNESCO delegation for further explanation of the plan. Because the park, and the caves within it, are a UNESCO World Heritage Site, any plan would need to comply with UNESCO’S operational guidelines for such sites, Hanh adds.

Around the world, caves stand a good chance of surviving if they are part of a protected landscape, says Culver, of American University. Opening caves to mass tourism inevitably has environmental impacts, he adds, but it is often a good compromise between economic development and conservation.

“You have to look at commercial caves as an educational opportunity,” Culver says. “If people start caring about it, then that’s the best protection of all.”