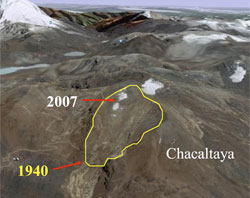

Earlier this year, the World Bank released yet another in a seemingly endless stream of reports by global institutions and universities chronicling the melting of the world’s cryosphere, or ice zone. This latest report concerned the glaciers in the Andes and revealed the following: Bolivia’s famed Chacaltaya glacier has lost 80 percent of its surface area since 1982, and Peruvian glaciers have lost more than one-fifth of their mass in the past 35 years, reducing by 12 percent the water flow to the country’s coastal region, home to 60 percent of Peru’s population.

And if warming trends continue, the study concluded, many of the Andes’ tropical glaciers will disappear within 20 years, not only threatening the water supplies of 77 million people in the region, but also reducing hydropower production, which accounts for roughly half of the electricity generated in Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador.

Chances are that many of Bolivia’s Aymara Indians heard little or nothing about the report. But then the Aymara — who make up at least 25 percent of Bolivia’s population — don’t need the World Bank to tell them what they can see with their own eyes: that the great Andean ice caps are swiftly vanishing. Those who live near Bolivia’s capital city of La Paz need only glance up at Illimani, the 21,135-foot mountain that looms over the city, and watch as its ice fields fade away. Their loss adds to a growing unease among the Aymara — and many Bolivians — who realize that the loss of the country’s glaciers could have profound consequences.

The Aymara worship the ice-draped mountains as Achachilas, or life-giving deities, whose meltwater is vital to a region that suffers a five-month dry season and relies on agriculture to survive. Now, as greenhouse gas emissions heat the earth, the Aymara are bracing for a future in which glaciers no longer can be counted on to supply life-sustaining water.

In recent decades, 20,000-year-old glaciers in Bolivia have been retreating so fast that 80 percent of the ice will be gone before a child born today reaches adulthood. So far this melting has brought temporary increases in stream flow and contributed to massive Amazonian floods that forced several hundred thousand people from their homes last year.

But within the next decade, scientists predict that this torrent of meltwater will turn into a trickle as glaciers shrink, meaning that the age-old source of water during the dry season will steadily dwindle. Some highland farmers near La Paz already report decreased water supplies.

“Here you have precipitation only part of the year,” said French glaciologist Patrick Ginot as he stood at 16,500 feet next to Zongo glacier last year. “But it’s stored on the glacier and then melting throughout the year, and so you have water throughout the year. If you lose the glacier, you have no more storage.”

In effect, underdeveloped countries such as Bolivia are paying dearly for the massive energy consumption of the United States and the industrialized world. The so-called “carbon footprint” of the average Bolivian peasant is negligible, yet Bolivia’s poor are not only among the first to feel the harsh effects of climate change, but also are sorely lacking the resources to adapt to it.

“The grand question here is, who compensates,” says Oscar Paz, director of Bolivia’s National Climate Change Program, “because we are not culpable for climate change. It’s not fair that a country like Bolivia, which emits 0.02 percent of global greenhouse emissions, already has annual economic losses from the impacts of climate change equivalent to four percent of our GDP.” These losses, about $400 million, are largely due to the recent Amazonian floods.

Bolivia is one of many countries, nearly all in the developing world, facing looming water shortages from melting glaciers. Up and down South America’s western coast, Andean glaciers are the natural water towers to tens of millions of people, including those in the capital cities of Quito, Ecuador; Lima, Peru; Santiago, Chile; and La Paz.

Underdeveloped countries are paying dearly for the energy consumption of the industrialized world.

Similarly, on the opposite side of the world, two billion people rely on meltwater from the Himalayas, which have lost 21 percent of their glacial mass since 1962. Himalayan glaciers are the main source of water for five major river systems whose flow irrigates much of China, India, and Pakistan’s rice and wheat and which also supplies much of the region’s drinking water. These river basins are the Ganges, with 407 million people; the Indus, with 178 million people; the Brahmaputra, with 118 million people; the Yangtze, with 368 million people; and the Yellow, with 147 million. Scientists predict that the Himalaya’s smaller glaciers will be gone by 2035 and that many large ones will disappear by century’s end, possibly leading to famine in a region whose population continues to soar.

“The world has never faced such a predictably massive threat to food production as that posed by the melting mountain glaciers of Asia,” Lester Brown, president of the Earth Policy Institute, wrote last year.

Studies show glaciers melting at alarming rates throughout the world, yet unlike mountains in higher latitudes, ice melts year-round off tropical glaciers, which are found on peaks close to the equator and receive the sun’s strongest rays.

“Glaciers, especially tropical glaciers, are the canaries in the coal mine for our global climate system,” Lonnie Thompson, a preeminent glaciologist from Ohio State University, said during a climate change forum in Peru last summer.

Bolivia’s glaciated mountains are almost all in the Cordillera Real, or Royal Range, which soars from the northwest to southeast of La Paz and its adjacent slum city, El Alto, separating the arid, windswept expanse of the altiplano (high plain) from the dripping verdure of the Amazon. Among these remote spires is a glacier that has become the most glaring symbol of Bolivia’s rapidly transforming cryosphere.

Called Chacaltaya, which means “cold road” in Aymara, the glacier was once Bolivia’s only ski resort and the world’s highest. Now it is a barren, russet moraine studded with clues of its past: a lonely chunk of ice sticking out like an elongated diving board and a dirty white signpost with the fading graphic of a cartoonish condor on skis.

Looking down from Chacaltaya, the significance of its disappearance hits home. In the distance, the corrugated tin roofs of El Alto gleam across the endless altiplano, which stretches like a placid brown ocean to the horizon. Water for the city’s nearly one million residents comes mainly from the region’s largest reservoir, situated at the base of a glaciated mountain cluster called Tuni Condoriri. Since 1983, the cluster has lost 35 percent of its ice mass. Glaciers Tuni and Condoriri, the two largest, are projected to disappear by 2025 and 2040, respectively, if not sooner.

Even closer is the glacier Zongo, the source for 10 cascading hydropower plants that provide a quarter of Bolivia’s electricity. These days, Zongo is receding 33 feet a year. To the southwest stands Illimani, and though scientists have not monitored its glacial retreat, residents of nearby Palca say it is extreme.

The Andean Regional Project on Adaptation to Climate Change (PRAA) says that Palca and two other townships are most reliant on meltwater for survival and the most vulnerable rural districts to glacial loss. Pure geography, the areas’ extreme poverty, and the lack of efficient irrigation methods are all factors.

Some residents already report decreases in flow, in part due to a drastic change in rainfall patterns. Worried about imminent water shortages, many Palca residents are migrating to the city or to other countries, such as Argentina. One irony of this migration is that many are moving from Palca to El Alto in hopes of a better life, yet water there also is running dry — the combined result of skyrocketing demand and diminishing natural reserves. A few decades ago, El Alto was just a small barrio next to the airport. In less than 20 years, the population has grown from 200,000 to 900,000, without any urban planning.

There is little time for Bolivia to adapt before major water shortages begin, but the government lacks the money to pay for them.

Edson Ramirez, Bolivia’s leading glaciologist, published a study several years ago warning that water shortages would soon begin in El Alto and the outskirts of La Paz and worsen over the next decade. His team plotted a curve approximating when the water demand will surpass the amount that glaciers on Tuni and Condoriri will provide.

“Right now there is not a major problem in El Alto because the additional glacial melt has compensated for the demand, providing more water flow,” says Germán Aramayo, the vice minister of water resources. “But we’re going to begin to have problems.”

In 1998, Ramirez and a team of French scientists presented Bolivian officials with the first results of their glacier-monitoring work, warning of the rapid retreat that was to come. No one believed them. Now there is little time to adapt before major water shortages begin. Nor does the government have the hundreds of millions of dollars needed to pay for these projects, which include building dams and reservoirs.

Victor Rico, the director of the public water utility, EPSAS, blames this lack of foresight on the political and economic upheaval that has plagued Bolivia, embodied by the bloody “Water War” of 2000, a fight over water privatization. President Evo Morales’s socialist government only created EPSAS in January 2007, after nationalizing its predecessor.

“This situation of who’s going to be in charge of the water companies created major conflict,” says glaciologist Ramirez. “But they were not looking at the core problem — what are we going to do when we no longer have this water resource?”

Many Bolivian officials believe that industrialized nations, the source of most greenhouse gases, have an obligation to help countries such as Bolivia mitigate the impact of climate change. Bolivia is planning to launch pilot projects in La Paz, El Alto, and four nearby communities that would, among other things, build more storage tanks to capture water in the rainy season; the World Bank will provide most of the funding. But far greater investment is needed to build larger reservoirs, help farmers acquire efficient drip-irrigation technology, tap into underground aquifers, and rebuild municipal water systems, some of whose pipes leak half the water they carry.

Meanwhile, concern grows in places such as Palca.

“When I was a boy, the snows covered practically all these hills, but now year after year, they are melting away,” says Roger Seja, leader of the Palca farmers’ union. “It’s very sad. How do we find a solution if nature herself, the universe itself, brings us this?”