Between 2010 and 2014, there were 15 polar bear attacks on humans, the greatest number ever recorded in a four-year period.

It might seem excessive to use military technology to detect bears, but the habits of polar bears in northern Canada are changing. As Arctic sea ice declines due to rising global temperatures, polar bears are spending more time on land and moving increasingly through populated areas, resulting in a rise in the number of bear attacks on humans in recent years.

Inside Tundra Buggy One, several colored squares inch along the map, representing the six or so tourist buggies nearby. “As soon as something comes on here, the camera swings,” York explains. Once the radar identifies a bear, it begins tracking it, sending out GPS locations to scientists and local authorities. Earlier this summer, the radar was set up in the nearby town of Churchill, Manitoba where it learned to identify people, quad bikes, and dogs. With enough data, the so-called BEARDAR system will be able to issue alerts to the local polar bear patrol team when a bear is in town, or remotely trigger deterrents, like flashing lights or loud noises, and a warning system that notifies passing pedestrians when they’re in close proximity to a wayward bear.

In a wide-ranging study published in 2017, scientists, including York, catalogued 144 years’ worth of recorded polar bear attacks on humans around the circumpolar Arctic. Between 1960 and 2009, there were a reported 47 attacks by polar bears on people, ranging between 7 and 12 per decade. Between 2010 and 2014, when sea ice extent reached record lows, there were 15 attacks, the greatest number ever recorded in a four-year period. Moreover, since 2000, 88 percent of attacks have occurred between July and December, when sea ice is at its lowest for the year.

Biologist Geoff York is developing a new radar system that will alert communities of approaching polar bears. Kt Miller / Polar Bears International

The study foreshadowed the events of the summer of 2018. In July, a subadult male polar bear attacked and killed a man who was berry picking with his children on Sentry Island, six miles outside the Inuit community of Arviat, Nunavut. Arviat, 150 miles north of Churchill on the edge of Hudson Bay, sits along the same polar bear migration route as Churchill. Then, at the end of August, a mother polar bear in Nunavut’s Foxe Basin attacked and killed an Inuit hunter, and injured two others, after they got between her and her cubs — the first known fatal attack by a mother polar bear.

In response, Inuit communities in Nunavut have called on the government to allow a higher legal polar bear harvest quota, arguing bear populations have increased to dangerous levels and should be reduced through hunting. Scientists counter that polar bear populations are declining, not increasing. The bears are simply spending more time on land in the absence of sea ice. Any increase in hunting, they say, could speed along the bear’s climate-caused demise.

The recent human fatalities have provided an impetus for developing new non-lethal conflict-reduction tools that can be exported to remote northern communities before more people, and bears, are killed.

Of the 19 global polar bear subpopulations, the majority are located in Canada, with 12 in the territory of Nunavut alone. Canadian wildlife officials say the two populations around Hudson Bay are declining. Since 1987, polar bears in Western Hudson Bay, where the Arviat attack occurred, have declined by approximately 30 percent, from 1,185 down to 806 in 2011. Between 2011 and 2016, polar bear numbers in Southern Hudson Bay dropped 17 percent, from 943 to 780, with a large reduction in yearling survival. The Foxe Basin bear population has remained stable.

Polar bear hunting is a critical source of revenue to northern communities, with pelts selling for around $5,000.

“What we’re seeing across the Arctic as sea ice recedes is that more polar bears are spending time on shore,” says York. “That’s true in all of the range states. We’re just getting more reports of bears, and bears occurring, too, in places they historically haven’t been seen before. At the same time, because of that same sea ice loss, we’re seeing more shipping, more tourism, more research, and more industrial activities in the Arctic. It really is creating that perfect storm of potential for human-bear conflict.”

Following the August attack, the Inuit hunters killed the mother bear and her two cubs. They then killed three more bears that were drawn in by the carcasses as a precaution in case they attacked. In the weeks that followed, there were more “revenge killings” of bears by the nearby community, with the animals left unharvested and unreported, says Andrew Derocher, head of the Polar Bear Lab at the University of Alberta. “It’s triggered a lot of resentment over harvest management in Nunavut, broadly, and specifically in Hudson Bay,” confirms York.

In November, the Nunavut government released a controversial draft polar bear management plan that stated there were too many polar bears roaming parts of the Canadian Arctic, and that they had not yet been affected by diminishing sea ice and climate change. Nunavut currently allows an annual allowable take of between 400 and 500 polar bears, but defense kills are included in this hunting quota. The hunt is a critical source of revenue to northern communities, with polar bear pelts selling for around $5,000. Killing a problem bear that may be in poor, sickly condition, then, means lost profits.

Inuit communities want such emergency kills to be removed from their quotas. When completed, the new Nunavut polar bear plan will guide bear management in the territory until 2026, updating the current management model that doesn’t incorporate traditional Inuit knowledge. “We know what we are doing, and Western science and modeling has become too dominant,” the Kitikmeot Regional Wildlife Board wrote as part of its submission for the draft plan.

The research vehicle Tundra Buggy One (in background) is used to track polar bears in Canada's Hudson Bay area. Simon Gee / Polar Bears International

“Pressure to conserve and protect polar bears from national and international environmental and non-governmental organizations, climate change advocates, and the general public at large has created contention about the status of polar bear populations,” the draft plan reads. A document submitted by Nunavut Tunngavik Inc, the Inuit land-claim organization, noted that, “The disconnect between the sentiment in certain scientific communities and [Inuit knowledge] has been pronounced.”

(Efforts to contact local government officials and indigenous leaders in Nunavut for comment were unsuccessful.)

Currently, the size of the polar bear population is estimated via aerial surveys conducted each spring, often by Derocher and his lab. He says not only are some polar bear populations declining, but they’re declining in part because of the legal harvest — which he says the Canadian government won’t touch. Canada is the only country in the world that allows for the commercial trade of polar bear parts. “The harvest is not sustainable here [in Western Hudson Bay],” he says. “I think there’s a reasonable chance that the last polar bear in Canada will be shot by an Inuk hunter.”

In December, an independent advisory panel to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada issued a statement noting that the polar bear was at risk of disappearing. “It is clear we will need to keep a close eye on this species,” Graham Forbes, a biologist at the University of New Brunswick and co-chair of the committee, said. “Significant change is coming to its entire range.”

As officials search for management solutions, Churchill could serve as ground-zero for successful human-polar bear coexistence.

Churchill may now be considered the first “polar bear safe community” in the world, says one wildlife biologist.

In the 1980s, the Polar Bear Holding Facility was established at an old military storage facility on the outskirts of town. Repeat offenders are trapped and transported to the facility every fall where they’re held for up to a month before being released on the sea ice, far from town. Churchill’s Polar Bear Control Program of the 1960s and ‘70s, which was responsible for euthanizing an average of 15 bears annually, has since evolved to become the Polar Bear Alert Program, with a dedicated hotline to report bears (it receives an average of 300 calls annually), and patrol teams roving the town to chase bears away with noisy scare cartridges and snowmobiles. In October and November, when bears are passing through the area to reach the sea ice of Hudson Bay, a team patrols daily at 7:00 a.m. to clear the town of any bears before pedestrians head out. There has not been a single human fatality since 1983.

Churchill may now be considered the first “polar bear safe community” in the world. “It’s a great natural setup for research, testing deterrents and systems like the radar system, and doing training for people in other communities,” says York.

Arviat also has a polar bear patrol team, funded through the World Wildlife Fund and the territorial government, with four bear guards tasked with driving bears away from the settlement, as well as a bear hotline and electric fencing around sled dog compounds. Even so, the patrol team is feeling stressed and says there’s little it can do to protect hunters when they are out in true Arctic wilderness.

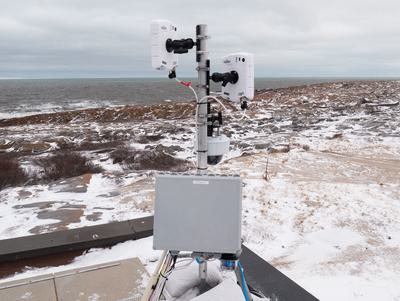

The BEARDAR radar system being tested near the shores of Hudson Bay. BJ Kirschhoffer / Polar Bears International

Increasing the hunting quotas could be one way to manage bears. But scientists are hopeful advances in technology, such as the so-called BEARDAR radar system, will be a better solution for coexistence in a changing Arctic. “When you can only see 30 feet, you’re going to miss bears,” says York from inside Tundra Buggy One. Once they finish teaching the system how to recognize bears, the researchers hope northern communities will be able to make use of the technology for their own defense needs.

In the early afternoon, we spot a female bear traversing the tundra. York and Derocher deem the bear to be in good condition as she pads along the tundra. But that’s not necessarily indicative of how things are going across the Arctic. The buildup of sea ice every year remains variable, with some good years and some bad years, and this largely determines the health of the bears.

“We’re watching this slow-motion train wreck,” says York. “We know if we continue on the path we’re on, there will be fewer and fewer bears. Some places like Hudson Bay, in my lifetime, might not have polar bears.”