Not long ago, David Crane and David Steiner were among a handful of Fortune 500 CEOs admired by environmentalists. A climate hawk and the chief executive of NRG Energy, Crane led the company as it invested $1 billion in solar power, wind energy, and electric-car charging. Steiner, chief executive of Waste Management, was an evangelist for recycling. “Picking up and disposing of people’s waste is not going to be the way this company survives long term,” Steiner told me back in 2009. “Our opportunities all arise from the sustainability movement.”

That was then, and this is now: Crane was abruptly fired last fall just before he was planning to leave for the Paris global climate talks. (He went anyway.) “The market was irritated with me over the green strategy,” he says. Steiner has turned bearish on recycling because of low commodity and energy prices, among other issues. “Momentum has been up, up, up for the last 20 years, and now, it’s stalling — it’s down, down, down,” he said recently. Waste Management has abandoned or closed 30 recycling facilities, 21 percent of the company’s total, since 2014.

Crane’s firing, which he has attributed to his green initiatives, and Steiner’s retreat raise important questions about the ability of big companies to manage — let alone lead — the transition to a low-carbon economy that scientists say is required to avert the worst impacts of climate change. “I think the problem was transformation,” Crane has written. “We were attempting to transform NRG from brown to green, and from centralized to distributed. Investors didn’t like it.”

Who, then, will lead the way to a low-carbon future? Startups like Tesla and Solar City may be best positioned to do so, just as Google, Amazon, and Facebook came out of nowhere to become three of the most valuable companies in the world. Peter Boyd — who has worked closely with big corporations as the launch director of the nonprofit Carbon War Room and an adviser to the B Team, a network of high-profile CEOs dedicated to fighting climate change — says the culture of startups gives them an edge.

“Entrepreneurs are going to drive transitions,” Boyd says. “They’ve got nothing to lose. They’ve got the focus. They may get bought up eventually, but the entrepreneurial spirit is going to be key.”

NRG, Waste Management, and other big companies face what’s known as “innovator’s dilemma,” a concept made famous by a book by Clay Christensen of the Harvard Business School, The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Christensen argues that firms with a big stake in the status quo tend to focus on current customer needs, revenues, and business models, and fail to adapt to new technologies or models designed to meet the future needs of customers. It’s why Blockbuster Video failed to become Netflix, why iTunes was built by Apple and not by a big music company, and why neither Marriott nor Hilton thought to start AirBnB.

In the energy and sustainability arenas, big firms have made only halting and uneven progress toward a greener future. Shell and BP made major investments in renewable energy in the 2000s, only to pull back. (Recall BP’s advertising campaign, “Beyond Petroleum”?) Ford promotes the idea of smart mobility, but it makes money from its hulking, gas-guzzling F-Series truck, which has been America’s best-selling vehicle of any type for 28 consecutive years. Walmart’s comprehensive sustainability program doesn’t prevent it from selling billions of dollars of cheap, throwaway goods, while GE, the company of “Ecomagination,” makes power plants that burn coal, natural gas, and oil.

Large companies often fail to adapt to new technologies designed to meet the future needs of customers.

Why, indeed, would any of them abandon profitable businesses that meet today’s needs?

“This is the hardest thing in management — how do you manage the transformation of a large organization?” says Alasdair Trotter, a partner at consulting firm Innosight. “You can’t go too fast. You can’t go too slowly. And there are so many stakeholders to be managed.”

Innosight was co-founded by Clay Christensen to help companies “design and create the future, instead of being disrupted by it.” But Trotter is hard-pressed to name more than a handful of companies that have negotiated major technology transitions successfully. IBM is the most often-cited case. It morphed from a manufacturer of high-priced mainframe computers to a provider of technology solutions and services, a turnaround so unlikely that its CEO, Louis V. Gerstner Jr., wrote a book about it, aptly-named Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance?

At NRG Energy, which he led for 12 years, Crane tried valiantly to get the electric utility sector to act more like startup companies. In a widely circulated shareholder letter in 2014 that reads more like a manifesto, he wrote:

There is no Amazon, Apple, Facebook or Google in the American energy industry today… There is no energy company that connects the consumer with their own energy-generating potential… And there is no energy company that the consumer can partner with to combat global warming without compromising the prosperous “plugged-in” modern lifestyle that we all aspire to… NRG is not that energy company either, but we are doing everything in our power to head in that direction, as fast as we can.

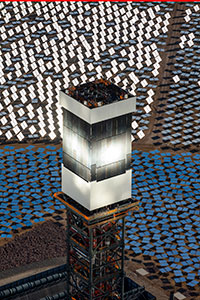

While the vast majority of NRG’s assets are power plants that burn coal or natural gas, Crane bulked up the company’s clean-energy portfolio and invested in a subsidiary, NRG Home Solar, that sells or leases rooftop solar panels to homeowners. Under Crane, NRG also became the biggest investor in the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System in the Mojave Desert, one of the world’s largest solar thermal plants. “We’re fanatically bullish on solar,” he once told me. In addition, NRG started EVgo, the U.S.’s first privately funded infrastructure of home-charging and public-charging stations for electric cars. Crane himself drove a Tesla and a Leaf.

None of this endeared him to Wall Street. Investors like a “story,” and NRG’s was muddled. It wasn’t a regulated utility company that appeals to so-called value investors seeking a steady stream of dividends. Nor was it a growth play. NRG’s share price fell from $27 at the beginning of 2015 to $11 just before Crane was dismissed. So did the stock prices of other independent power producers, as he has noted.

Waste Management, too, faced investor pressures as analysts degraded the stock, and its share price fell during the first half of last year. The economics of recycling are partly to blame. “In some quarters, we lost money in recycling,” says James Fish, Waste Management’s chief financial officer. “In quarters when we made money, it was very little.” The company, which invested more than $1.5 billion in new recycling facilities and technologies over the years, has stopped that spending.

The recycling business faces stiff headwinds. The global economic slowdown, particularly in China, has led to low commodity prices. That means that the value of recycled commodities, such as newsprint, plastics and aluminum, has declined. In addition, the economics of waste-to-energy technologies are challenged by low oil and natural gas prices.

Not only that, the makeup of garbage has changed, and not in a helpful way. Hard-to-recycle pouches made of layers of plastic and aluminum — the ones that hold baby foods and juice — have become ubiquitous. Newsprint volumes plummeted by more than 50 percent along with newspaper circulation. Aluminum cans and plastic bottles have been “lightweighted” for environmental reasons, but the results is that trash haulers have to collect and process more of them to produce the same volume of recycled aluminum or polyethylene terephthalate plastic, known as PET. A Waste Management official says it now takes 97,000 plastic bottles to make a ton of recycled PET. It used to take 60,000 bottles.

Younger firms can be more nimble, but they often don’t have the resources to drive change on their own.

Notwithstanding those challenges, companies that are devoted to recycling say there’s nothing wrong with the business. Lakeshore Recycling Systems of Morton Grove, Illinois, and Balcones Resources of Austin, Texas, are privately held recyclers that don’t own landfills and aim to grow. They are careful to draft contracts with municipalities and commercial customers that share the financial risks and benefits of recycling. Customers are paid more when commodity prices are high, and less when they are low, which helps smooth out the ups and downs of commodity prices.

Balcones has been profitable in 20 of its 22 years, according to Kerry Getter, the founder and CEO, who previously worked as a regional recycling manager for Waste Management. He says of his former employer: “They make money whether they recycle or whether they haul to the landfill. It’s very difficult to serve two masters.”

Mark Milstein, a professor of management at Cornell University who focuses on sustainability, agrees that “younger firms can be more nimble and risk taking,” but he says they don’t have the resources to drive change on their own. He’s been impressed, he says, by the embrace of new, sustainable business models at companies like DuPont and Dow. “Big companies have deep pockets and are able to do incredible things at scale,” he says.

But John Hofmeister, the former president of Shell, says government needs to lead the transition to a low-carbon economy. Shell invested in wind and solar energy in the 2000s because it anticipated that governments would regulate carbon emissions from fossil fuels.

In 2007, Hofmeister joined with David Crane, GE’s Jeff Immelt, CEOs from the auto and energy industries, and big environmental groups to form the United States Climate Action Partnership. It called on the government to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, in a tacit admission that even the biggest companies can’t solve the climate problem on their own. When Congress failed to enact limits on carbon emissions, companies, including Shell, backed away from their low-carbon investments.

“Without government leadership, it is ultimately a futile effort for individual companies to step out and do it by themselves,” Hofmeister says. “If we don’t have a legislative framework, there’s only so much we can do.”

His takeaway? “Never, ever, ever underestimate the power of the status quo. It is huge.”