Costa Rica has a green halo. In recent decades, the small Central American nation has transformed itself from a notorious hotspot for deforestation into a beacon of reforestation that is the envy of the world. Many of its more than 12,000 species of plants, 1,200 butterflies, 800 birds, and 650 mammals, reptiles, and amphibians have gone from bust to boom, and eco-tourists are savoring the spectacle.

But some outsider observers are now asking if the success can be sustained without a similar breakthrough in restoring the land rights of its dispossessed Indigenous communities, the ultimate custodians of the forests.

Opinion makers from Jeff Bezos to Leonardo DiCaprio to Britain’s green-minded royal heir Prince William have lined up to praise the country’s environmental credentials. “Costa Rica has been a pioneer in the protection of peace and nature and sets an example for the region and for the world,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, making the country the UN’s Champion of the Earth in 2019.

But the apparent green paradise hides a dark side. Almost invisible to the outside world, a long-running conflict over the land rights of the country’s forest-dwelling Indigenous communities threatens to undermine this re-greening and is turning its pacific forests into battlegrounds.

Land disputes in Costa Rica have escalated, leading to violent clashes and the assassinations of two Indigenous leaders.

For almost half a century, Costa Rica has had laws requiring the state to take back Indigenous territories grabbed by ranchers decades before and return them to their traditional owners. But theory and practice have proved very different. Political and legal stasis have left the Indigenous Law enacted in 1977 largely unimplemented.

In the past decade, Indigenous communities have grown impatient, taking the law into their own hands. The result has been escalating disputes and repeated violent clashes deep in the forests. Since 2019, two Indigenous leaders have been assassinated for attempting to reclaim their traditional lands, and others have barely escaped with their lives.

After visiting Costa Rica in late 2021 to interview all the parties involved, the UN special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples, Guatemalan diplomat José Francisco Cali Tzay, sided with those trying to reclaim their lands. He attacked the “40 years of non-compliance by the State of Costa Rica with the Indigenous Law,” and in a report to the UN’s Human Rights Council last July, criticized the “structural racism that pervades the judiciary, especially at the local level,” in Costa Rica, “and the impunity for crimes committed against land defenders.”

The funeral of Jehry Rivera, a Costa Rican Indigenous leader who was killed in a land dispute in 2020. JUAN CARLOS ULATE / REUTERS

Last month, a Costa Rican court finally convicted one of the assassins, bringing hopes of an end to that impunity. But many fear that the election last April of a new populist president, supported by the farming community, could scuttle efforts to resolve the disputes. That would threaten to set back to the cause of reforestation too, as there is a growing international recognition that the best forest stewards are typically the Indigenous communities that live in them.

Costa Rica’s forests have seen a dramatic turnaround in recent times. Between 1960 and the late 1980s, the country — which is somewhat smaller than West Virginia and has just over 5 million inhabitants — suffered from one of the fastest rates of forest loss in the world, at times approaching 4 percent annually. The rapid deforestation was driven largely by the rising international demand for beef. The U.S. government offered Costa Rican ranchers soft loans to clear forest and keep up with demand. At one point, the country reportedly sold 60 percent of its beef to Burger King.

Historical deforestation data for the country is poor, but under this onslaught it is reckoned that tree cover declined from as much as 75 percent in 1940 to below 40 percent — and by some measures as little as 17 percent — in the 1980s.

But as denuded hillsides led to landslides, droughts, and flooding, Rafael Calderón, the country’s then-president, turned the policy ship around. Inspired by the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, he set up a system of incentives, known as Payment for Environmental Services. The proceeds of a new fuel tax paid landowners and Indigenous communities to protect existing forests and nurture new ones, whether by planting or allowing natural regrowth on abandoned pastures.

Ecotourism has made Costa Rica the most visited country in Central America, with tourism revenues tripling.

The move went down well with ranchers, who were then being hit by falling international beef prices, and the policy and payments persisted through successive governments. To date, says Elena M. Florian-Rivero of the Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center in Turrialba, Costa Rica, around a fifth of the country’s land area has benefitted from the payments, which have totaled some $500 million. They underpin the majority of the reforestation.

And landholders found new ways to make money from this land. Cashing in on a growing international interest in ecotourism, many ranchers replaced cattle with lodges in the greenery of their regrowing forests. With a further quarter of the country, including half its forests, inside a network of 30 national parks and nature reserves, visitors have had plenty of nature to savor.

Ecotourism has made Costa Rica the most visited country in Central America, with tourism revenues tripling to $3.3 billion per year in the two decades prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile international funding for conserving the forests to capture atmospheric carbon dioxide has also increased. Last year, Costa Rica became the first Latin American country to benefit from the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility, receiving $16.4 million in 2018 and 2019.

During the UN climate conference in Glasgow in 2021, then-president Carlos Alvarado, basking in celebrity status unusual for the leader of such a small country, unveiled further funding from LEAF, a coalition of the United States, Britain, Norway, and private corporations aimed at raising money for projects to avoid deforestation. Forests now again cover around 60 percent of the country, stabilizing ecosystems and river flows.

But not all has gone well. By some estimates, around a third of the country remains cattle pasture. Some areas where reforestation received financial support have since suffered a new round of deforestation. J. Leighton Reid, a restoration ecologist now at Virginia Tech, found in 2018 that in Coto Brus county in Puntarenas province, half of regenerated forest patches had been cleared again within 20 years . Elsewhere, pasture and forests alike have been replaced by pineapple plantations, turning Costa Rica into the world’s biggest exporter of the fruit.

And there is growing concern about the rights of Indigenous communities living in the forests. In particular, the government has failed to make good on its promise to allow traditional forest custodians to reclaim their lands.

Many believe that, while financial incentives for conservation by non-Indigenous landowners may come and go, only Costa Rica’s Indigenous communities with their cultural and spiritual links to the forests can guarantee their future. Internationally, a review of 130 local studies in 14 countries, conducted by the World Resources Institute in 2014, found that community-owned forests suffer less deforestation and fewer fires, while storing more carbon than other forests.

Far from aiding recovery of Indigenous lands, the government plan has become “an instrument for postponing restitution.”

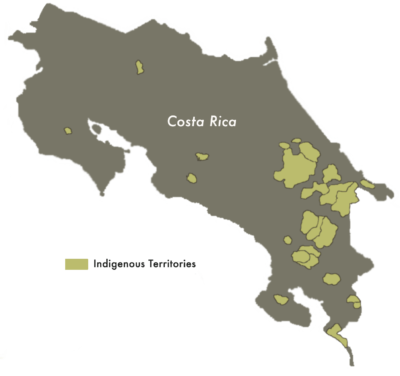

Costa Rica passed its landmark Indigenous Law in 1977, declaring all Indigenous territories to be “inalienable” and “exclusive for the Indigenous communities that inhabit them.” Twenty-four territories, covering some 7 percent of the country, were formally declared as Indigenous land, and theoretically set aside for restoration to their rightful owners.

But practice has proved rather different. Cattle ranching by non-Indigenous people still covers around a half of the formally-titled Indigenous lands, leaving many of the country’s 100,000-plus Indigenous inhabitants landless. To date, says Florian-Rivero, only two of the 24 territories have been fully restored to their rightful owners; and in seven territories less than a quarter of the land has been returned.

Flaws in the original legislation created a yawning gap between policy and reality on the ground. The government made available few funds for the promised compensation to people giving up their land. And the authorities have failed to legally recognize traditional representatives of the Indigenous communities.

Rather, the government imposed a network of development associations to receive the land, creating internal conflicts among Indigenous communities. Local officials say this has exacerbated disputes over who is and who is not genuinely Indigenous, and who has the right to decide. Some groups, being traditionally matrilineal, require proof of an Indigenous mother, for instance, while others accept ancestry from either gender.

In 2010, faced with this impasse, the leaders of two Indigenous communities, the Bribri and the Brörán, began a campaign of unilateral recovery of their titled lands. These campaigns have typically involved giving those they regard as squatters a deadline to quit and remove their livestock, after which Indigenous people arrive en masse to take over.

The Bribri of Salitre claim to have recovered 49 farms covering up to 80 percent of their ancestral territory. Brörán leader Pablo Sibar says that a total of about 30,000 acres have so far been recovered in five territories: Salitre, Cabagra, Térraba, China Kichá, and Guatuso.

But it has been a sometimes bloody process, with both sides accused of violent attacks and two Indigenous leaders shot dead.

Faced with increasing lawlessness in its forests, the government has tried to intervene. In 2016, it launched a National Plan for the Recovery of Indigenous Territories, aimed for completion within six years. But this too has proved ineffective, says Cali Tzay, the UN special rapporteur. Indeed, far from speeding up recovery of Indigenous lands, he concluded last year, the plan’s complex procedures threaten to become “an instrument for postponing restitution.”

Tensions have escalated since the plan’s inception. One evening in March 2019, longtime Bribri leader Sergio Rojas was assassinated in his home in the remote village of Yeri in Puntarenas province on the Pacific coast, hours after lodging a formal complaint about land grabs. Police found him with seven bullet wounds in his back.

The country’s newly elected president has backtracked on his predecessor’s support for open environmental governance.

Eleven months later, Brörán leader Jehry Rivera was also shot dead as an organized mob of more than a hundred local farmers confronted his people who were reoccupying land in the Térraba Indigenous territory.

Last month, the man convicted of shooting Rivera was sentenced to 22 years in prison. “The conviction is a definite positive message against impunity,” says Nathalia Ulloa, a human rights lawyer and national coordinator for the U.K.-based Forest Peoples Programme. “But it has also aroused more hate from those who support the murder.” She says the house of the only direct witness, who lives alone with her baby and is seven months pregnant, has been attacked.

Meanwhile, the slayer of Rojas is still at large.

In 2018, leaders of the Cabécar people followed the Bribri and Brörán and attempted to reoccupy their China Kichá territory. The 18,500 acres, in San José province, has been disputed ever since its titling.

Its Indigenous status was repealed in 1982, then reinstated for part of it in 2001. But by then, most of the forest had been converted to coffee plantations and cattle pastures. Despite the reinstatement, a study by the Forest Peoples Programme in 2014 found that 97 percent remained in the hands of outsiders, leaving the Indigenous China Kichá community as “impoverished day laborers working on their own lands.”

Under a new leader Doris Rios, the Cabécar community subsequently recovered two-thirds of its territory, which it is attempting to reforest. But it has faced a campaign of arson targeting its crops and community buildings. Thirteen members were injured during a confrontation with farmers in February 2022. And two months later, Rios’s teenage son Dario was knifed in the head. “The police say it was a fight, but this was an assassination attempt,” she says.

Rios is proving an icon for supporters of the movement to restore Indigenous lands and protect forests. Last year, she received an award from the National University of Costa Rica. The head of the school of anthropology praised the “earth-colored women who care for the forests … talk to the plants, know their pain and healing mysteries.”

And earlier this month, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken made Rios one of 11 recipients of the 2023 International Women of Courage Award during a ceremony at the White House, citing her work on recovering Indigenous land.

But plaudits don’t deliver land or protect forests, and the political landscape in Costa Rica may be changing, to the detriment of both environmental concerns and land rights. In April last year, the country voted in a new right-wing populist president, Rodrigo Chaves, who counts farmers as part of his political base. He has installed a former farmers’ leader as CEO of the Rural Development Institute, which oversees the National Plan for the Recovery of Indigenous Territories.

Chaves has also backtracked on his predecessor’s support for open environmental governance. He has shelved plans to ratify the 2018 Escazú Agreement, under which Latin American and Caribbean nations promised to enhance public participation in environmental decision-making.

This step compounds existing long-standing policies of preventing Indigenous communities from using their traditional expertise to help manage the country’s protected forests. Cali Tzay, the UN special rapporteur, identified frequent conflicts where state-protected forests and Indigenous territories overlap, with Indigenous people prevented from accessing sacred places or carrying out traditional hunting or fishing activities. “Although the Indigenous peoples have been caring for the forests for centuries,” he says, “they are not taken into account in the management of protected areas.”

Costa Rica is known for its peaceful outlook on the outside world. It has had no armed forces for more than 70 years. Yet it now risks stumbling into a rising tide of conflict that threatens to unravel the country’s impressive green gains of recent years.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.