Yale Environment 360: How do you study ancient fires in British Columbia?

Lori Daniels: The work that we do is largely in the drier forest types, where Douglas firs, Ponderosa pines, and Western larches and lodgepole pines are all excellent recorders of fire.

When there’s a surface fire that burns past the base of the tree, it heats up and kills part of the growing tissue just under the bark of the tree on one side. What you end up with is literally a section of the tree rings that stop growing, and then the rest of the tree rings form kind of a scab over top. Under a microscope, we can work out the exact year of the fire and sometimes the season.

Our most exciting discovery was the Ponderosa pine with the most fire scars recorded in a single tree across all of North America. It came from Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi’it, which is the Tobacco Plains on the Ktunaxa Nation traditional territory in southeast British Columbia. It bears 52 fire scars in a single tree that lived from the early 1400s to the late 1880s.

e360: What do these records show?

Daniels: Surface fires were a critical part of how ecosystems functioned throughout our mountain systems going back at least 850 years, which is as far as our tree ring records go. Before that, paleo records of pollen and char in lake sediments support histories of frequent fires since time immemorial.

In British Columbia, low-intensity surface fires burned in grasslands and open, dry forests once every five to 10 years, on average. As you move higher in elevation, those fires became a little bit less frequent, but they were still every 25 to 40 years. We know a lot of this was cultural use of fire, because we see repeat fire scars in the trees adjacent to culturally important sites.

“Some Indigenous collaborators have told us that their ancestors were hanged for lighting cultural fires on their territory.”

We also see evidence in the seasonality. The wildfire season is primarily in July and August. If we have a lot of fire scars in early spring, that hints of human ignitions from intentional cultural fire.

Those fire scars stopped — and this is a common pattern throughout North America — in the late 1800s to early 1900s exactly when European settlers arrived: Indigenous people were terribly impacted by smallpox and forcibly moved from their traditional territories to reservations. In British Columbia, the 1874 Bush Fire Act made it illegal to intentionally start a fire in the forests, and that was punishable by jail time or death. Some Indigenous collaborators have shared with us that their ancestors were hanged for lighting cultural fires on their territory.

e360: Are these results surprising?

Daniels: Many people — including some fire and forest managers — are surprised to learn that fires were so frequent in the past.

Really, all our tree rings have done is provided some Western science that is consistent with the oral histories shared by the Indigenous knowledge holders who we have the pleasure of working with and learning from. It’s a little bit sad, and a little bit of an indictment of our society, that until the tree rings verified those oral histories, there was resistance from our dominant colonial culture to believe that Indigenous people used fire to steward the land.

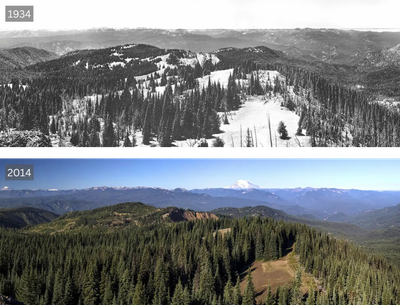

Forest in Kittitas County, Washington, in 1934 and 2014, after decades of fire suppression. George B. Clisby via National Archives; John F. Marshall / U.S. Forest Service

e360: How did the ending of cultural fire in the late 1800s change these forests?

Daniels: Surface fires used to control how many trees there were growing on the site: All the seedlings and saplings were removed. The forest was maintained as an open forest with a grassy understory and diverse plants. The Indigenous peoples were cultivating those plants as foods, as medicines, for ceremony, maintaining open forests where the fire severity was lower in and around their communities and cultural heritage sites.

What we see today is an absence of those surface fires. Seedlings have grown into the sites. We have found that two-thirds to three-quarters of the trees in these forests today started to grow after the surface fires stopped. The density of the forests is very high in some cases, not just hundreds of trees, but thousands of trees per hectare. That’s flammable fuel.

Now we have these forests that have far more trees, and it’s been decades since the last fire. We have dead biomass on the ground. This creates the ladder fuels that allow fire to become intense on the surface and then spread vertically up into the canopy of the trees. And then there’s no patchiness on the landscape. We’ve just got these massive areas that all have the same high abundance of fuels with no fuel breaks. So, it’s really the perfect storm.

The other thing we’ve learned, which is a little bit shocking, is in the dry forest types, when it rains, the small trees’ root systems are up near the surface of the soil, and they’re taking all the moisture out of the soil, rather than it seeping down deep into the soil. And so, the large trees that are hundreds of years old [with very deep roots] — and are really valuable for creating old-growth structures and wildlife habitat — are suffering the most during droughts.

“Today, we have basically eliminated surface fires, and we really only see the intense fires that escape suppression.”

e360: Is the idea of managing forests with prescribed burns controversial? I have seen some arguments that treatments such as selective logging and prescribed fire can dry the forest and make it more prone to burning.

Daniels: That’s true in some forest ecosystems. The only study I know in British Columbia that documented this did measurements the year after the treatments — in 2021, during the heat dome. It concluded that the treatments had no effect in August in terms of making it hotter or drier, because by then it was hot and dry anyway and everything could burn.

I would also say, in my experience, the people who are opposed to these kinds of treatments are often opposed to any trees being cut. They are also ill-informed or surprised to learn that Indigenous people used to manage the lands that they are trying to protect.

There’s a school of thought that you can just put a fence around a forest and keep people out, and it will be protected, which is a very old-school view, a very colonial view. It comes from this idea that we came to a land that was “empty” and there for the taking. They were not empty lands that happened to look like that. They were being actively managed.

Today, we have basically eliminated surface fires, and we really only see the subset of intense fires that escape suppression and burn during extreme fire weather to cause tremendous damage. This reinforces societal perceptions that fire is “only bad” and fuels skepticism that historical fires were diverse and often beneficial.

Members the Yunesit’in cultural fire crew set controlled burns on their ancestral territory in the Tsilhqot’in Nation. Josh Neufeld / Gathering Voices Society

e360: If we simply let natural wildfires burn instead of putting them out, would this do the job of fixing forests for us?

Daniels: Not fully, because the fires that we’re seeing today are burning at very high severity, and they’re very large. So we’re changing the structure of the forest, and it tends to be self-perpetuating. Once you’ve had a high-severity fire, you’re more likely to grow back a [dense, uniform] forest structure that’s susceptible to high-severity fire. So just passively trying to let Mother Nature fix herself is not going to work.

e360: North America is vast. Is it really possible to scale up prescribed burning to the appropriate amount?

Daniels: We can’t do it everywhere all at once, but we can triage, and we can be really strategic. We probably need to change about a third of the landscape in western North America to create the resilience we need. In British Columbia we manage about 22 to 24 million hectares for timber, which is more than a third of the 60 million hectares of forest across the province. If we had changed our forest management in British Columbia after the 2003 fires to manage for resilience [creating patchworks of different ages and lower densities of trees] instead of managing for timber production, we would have already made [the needed] changes to 3.5 million hectares of forest.

e360: Even if we do successfully manage the landscape in North America this way, will the increase in “fire weather” from climate change outweigh any positive changes we can make? Will wildfires still burn hot and large and out of control, regardless?

Daniels: Certainly, in some parts of British Columbia and some parts of Canada, particularly in the north, that’s going to be very true. We can just give up, or we can know that we can make the changes, and we can have positive effects. It won’t be next year or even in the next 10 years. It’s going to take cumulative change over time. This might not benefit us, but it will be the difference between having functional ecosystems to manage for timber and that people can live in and in which we can sustain biodiversity, 20, 50, 100 years from now.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.