In 2013, Song Shen Zhen, a 75-year-old resident of Calexico, California, was attempting to re-enter the United States from Mexico when border patrol noticed a strange lump beneath the floor mats of his Dodge Attitude. The plastic bags beneath the mats contained not cocaine, but another valuable product: 27 swim bladders from the totoaba, a critically endangered fish whose air bladders, a Chinese delicacy with alleged medicinal value, fetch up to $20,000 apiece. Agents tracked Zhen to his house, where they discovered a makeshift factory containing another 214 bladders. Altogether, Zhen’s contraband was worth an estimated $3.6 million.

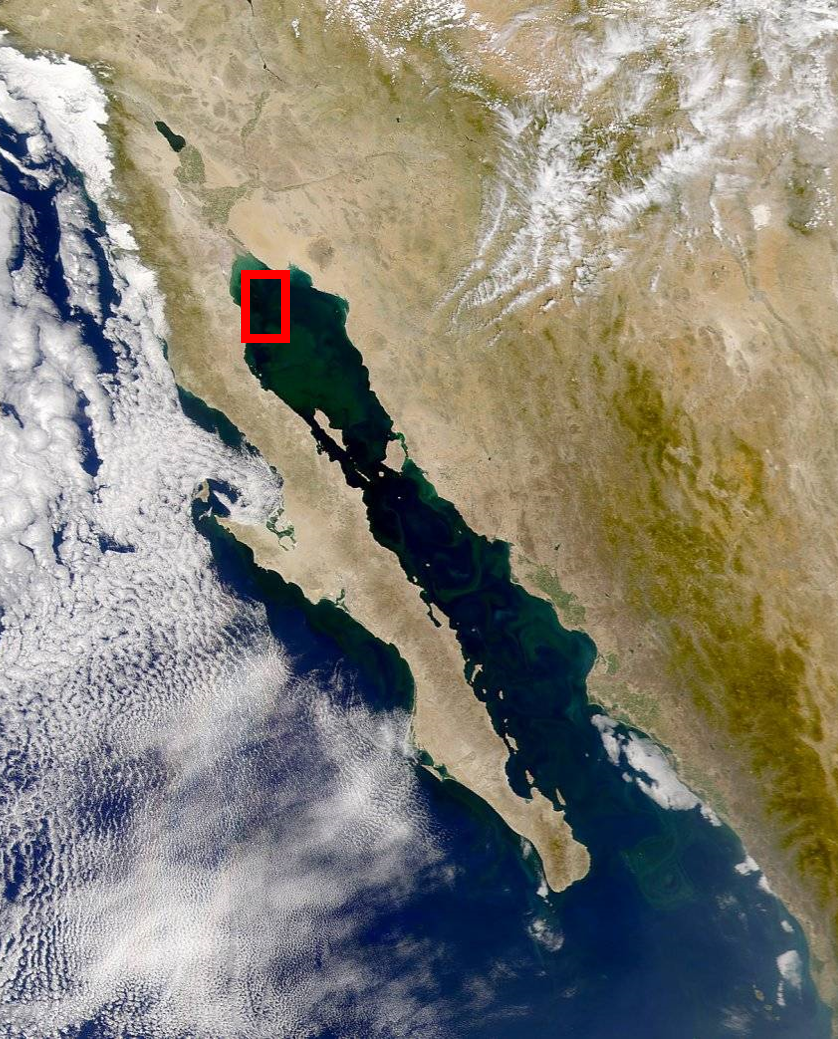

The robust black market is grim news for totoaba — but it’s an even greater catastrophe for vaquita, a diminutive porpoise that dwells solely in the northernmost reaches of the Gulf of California, the narrow body of water that extends between the Baja Peninsula and mainland Mexico. Since 1997, around 80 percent of the world’s vaquitas have perished as bycatch, many in gill nets operated by illegal totoaba fishermen.

Today, fewer than 100 vaquitas remain, earning it the dubious title of world’s most endangered marine mammal. Scientists fear the porpoise could vanish by 2018. “The possible extinction of the vaquita is the most important issue facing the marine mammal community right now,” says Barbara Taylor, a conservation biologist with the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center.

The vaquita — “little cow” in Spanish — is a creature of superlatives. Not only is it the most imperiled cetacean, it is also the smallest, at less than five feet long from snout to tail, and the most geographically restricted: Its entire range could fit four times within Los Angeles’ city limits. Prominent black patches ring its eyes and trace its lips, giving Phocoena sinus a charming, panda-like appearance. The porpoise, which typically travels in pairs or small groups and communicates using rapid clicks, is famously cryptic; conservationists recently went two years without documenting a single sighting. Some Mexican fishermen insist the vaquita is already extinct, photographic evidence notwithstanding.

The vaquitas’ blunt heads squeeze perfectly into the mesh of gill nets, entrapping and drowning them.

The secretive porpoise shares the upper Gulf with the totoaba, a slow-reproducing fish as large as a football linebacker, that returns to the region’s warm waters every year to spawn. In the 1920s, villages sprang up in the northern Gulf to harvest the fish, exporting its bladders to China and fillets to the U.S. But decades of overfishing decimated totoaba stocks, and in 1975 Mexico banned the fishery.

The prohibition helped reduce bycatch of vaquitas, whose blunt heads squeeze all too perfectly into the mesh of totoaba gill nets, entrapping and drowning the porpoises. But other gill net fisheries, particularly for shrimp, continued to kill vaquitas, and their population ticked downward for decades. In 1993, the Mexican government finally took action, designating a gill-net-free “biosphere reserve” in the area where the Colorado River once flowed into the Gulf. The reserve was far from perfect — the biosphere was rife with illegal fishing and enforcement was lax — but other regulations, including an expanded protected area, followed in 2005. The Mexican government also spent millions of dollars compensating fishermen to switch to vaquita-safe gear or quit fishing altogether.

By 2011, hope was running higher within the vaquita conservation community than it had in years. The porpoise’s numbers were still dropping, but they were no longer in free fall. Soon, scientists believed, its population would begin to climb.

That brief optimism, however, was quickly crushed by global market forces. During the Great Recession, a Chinese financial stimulus package flooded the nation with cash, fueling all sorts of speculative investments, including for dried fish bladders, or “maw,” a popular ingredient in soup, which increased in price exponentially. Though China had traditionally obtained its bladders from a native giant croaker, called the bahaba, overfishing had nearly wiped out the species. Chinese investors looked back to Mexico.

“There has always been a little illegal totoaba fishing,” says Lorenzo Rojas-Bracho, head of marine mammal conservation and research for the National Institute of Ecology and Climate Change (INECC) in Mexico. The 2011 price spike, however, “changed the game,” he says. Scientists began finding totoaba carcasses on the beaches, their bladders cut out and meat left to rot; fishermen bought new houses and registered multiple boats under the same license. “There was so much money flying around,” Rojas-Bracho recalls. “You could make as much money as drugs, without going to jail for years if you got caught.”

The surge spelled disaster for vaquitas. The porpoise’s population, which had been dropping by about 4.5 percent per year, began to plummet by a whopping 18.5 percent annually. In 2012, Rojas-Bracho’s team estimated that around 200 vaquitas remained. By the time the scientists reconvened in 2014, the animal’s numbers had dwindled to around 97, just a quarter of which were adult females. The world had lost half its vaquitas in three years.

Conservationists flew into crisis mode, urging the Mexican government to further intervene. In April 2015, President Enrique Peña Nieto traveled to the coastal village of San Felipe to announce a dramatic recovery plan. The plan’s highlights included an expanded vaquita refuge; improved enforcement by the Mexican navy; and a two-year ban on all gillnetting across a 5,000-square-mile swath of the Gulf. (Scientists want the ban to be made permanent.) In place of gill nets, legal fishermen would be trained to use vaquita-friendly nets and gear — traps for finfish like grouper, light trawls for shrimp — an important concession in a poor region where fishing provides one of the few sources of livelihood. “You can’t save the vaquita but have fishermen go extinct,” says Rojas-Bracho.

According to Omar Vidal, director of the World Wildlife Fund in Mexico, 30 of the upper Gulf’s 625 fishermen conducted tests this season using the alternative nets, which are designed to prevent vaquitas and sea turtles from getting ensnared. “Gill nets are still probably more efficient,” he acknowledges. “But fishermen are very resourceful people, and with time and experience they will improve their capabilities.”

U.S. consumers may also have a role to play. The upper Gulf’s most valuable legal fishery is blue shrimp, succulent crustaceans served in upscale restaurants throughout the U.S. According to Sarah Mesnick, a NOAA ecologist, around 80 percent of the blue shrimp captured in the Gulf of California end up across the border. If wholesale buyers were willing to pay a premium for blue shrimp netted with vaquita-friendly gear, Mesnick says, fishermen would have more incentive to adopt light trawls.

Still, if totoaba poachers continue to overrun the region, all the shrimp trawls in Mexico may not save the vaquita. The good news is that the Mexican navy’s patrols — conducted by powerful new vessels, light aircraft and drones — have slashed the number of illegal boats plying the gulf. The navy’s efforts have been aided by the marine conservation group Sea Shepherd, which pulls up illicit nets when it finds them. In their race against law enforcement, however, poachers have grown ever more cunning. To avoid detection, for instance, illegal fishermen have begun replacing their big, brightly colored marker buoys with inconspicuous Styrofoam cups.

Poaching persists, says Rojas-Bracho, because the rewards far outweigh the risks. Smugglers apprehended in the U.S. face stiff penalties: Song Shen Zhen, the smuggler from Calexico, was hit with a $120,500 fine and sentenced to a year in prison. But Mexican fishermen can get away with fines as low as $500, a fraction the value of a single bladder. That may soon change: A proposal recently put forth by a group of Mexican fishermen would make fish poaching and smuggling a major felony, on par with drug trafficking. Rojas-Bracho says the legislation is almost certain to pass eventually, though it’s not a top priority for the government.

“At the end of the day, you won’t be able to save the vaquita unless you stop the market in China.”

On the other side of the world, conservationists contend, Hong Kong and China aren’t pulling their weight in the fight against smuggling. A 2015 Greenpeace investigation identified 13 Hong Kong seafood shops that sell totoaba bladder, also known as Jin Qian Min, or “money maw.” Greenpeace found that Chinese businessmen typically did the buying — not for consumption, but for collection, as though stockpiling gold. “Almost all traders agreed that Hong Kong customs were very loose and had very little knowledge about the bladders,” the group reported.

“At the end of the day, you won’t be able to save the vaquita unless you can stop the market in China,” WWF’s Vidal says.

Time is not the porpoise’s ally. The vaquita takes up to six years to reach sexual maturity and only gives birth every other year, unlike most porpoises, which calve annually. According to NOAA’s Taylor, it could take 40 years to recover the vaquitas that have died in the last half-decade alone. Captive breeding is considered too risky, given the possibility of harming the few remaining vaquitas during capture or transport.

“We’re on this roller coaster that’s typical for endangered species,” Taylor says. “We take several progressive steps, and then we crash again.”

In 2006, Taylor witnessed the ultimate crash: the disappearance of the Yangtze River’s baiji dolphin, the planet’s previous most endangered marine mammal. For a month, Taylor and an international research team cruised up and down the Yangtze with acoustic detectors, listening for the baiji’s whistles. They heard nothing but boat engines, saw nothing but factories spewing green sludge into the river. By the cruise’s end, researchers believed the baiji to be extinct — history’s first human-caused cetacean extinction.

Though the vaquita’s future looks bleak, Taylor points out that the porpoise has one crucial advantage over the baiji. Compared to the Yangtze River, the Gulf of California offers pristine habitat, mostly devoid of boat traffic and free of pollution. That makes vaquita recovery more manageable — and the campaign against bycatch more urgent. Says Taylor: “If we can’t save vaquitas here, where there’s only one threat, what can we save?”