On the afternoon of January 10, at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, whale researchers Robert L. Pitman and John W. Durban stood on the bridge of a cruise ship, peering through binoculars for signs of killer whales. The Weddell Sea, where English explorer Ernest Shackleton and his men were locked in the sea ice nearly a century ago, was calm and studded with icebergs. It was raining, an increasingly common occurrence in summer in this rapidly warming part of Antarctica.

Around 3 p.m., Pitman spotted several of the distinctive triangular dorsal fins of killer whales two miles ahead. Soon, roughly 40 killer whales appeared on all sides of the cruise ship, the National Geographic Explorer, delighting the nearly 150 passengers on board.

Thus began more than a month of killer whale research in the Antarctic, conducted by two of the world’s leading experts on these top predators, whose killing power, Pitman says, “probably hasn’t been rivaled since dinosaurs quit the earth 65 million years ago.” I was a lecturer aboard the Explorer, and was able to watch the pair work for more than a week in the Antarctic.

As many as 50,000 killer whales roam the world’s oceans today, and roughly half of them are believed to live in Antarctic waters. Yet though killer whales may be the most recognizable creatures in the marine world, a

Baseline data is key as climate change and other human impacts rapidly alter the whales’ habitats.great deal about them remains a mystery, especially in the Antarctic, and Pitman and Durban are now gathering basic information about their behavior and feeding habits . This baseline data is particularly important since climate change and other human impacts, such as overfishing and the accumulation of toxic chemicals, are rapidly altering the whales’ habitats and their prey.

Scientists worldwide are still sorting out how many species and sub-species of killer whales — also known as orcas — exist in places like Alaska, the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. and Canada, and the North Atlantic. In Antarctica, Pitman and Durban — who work for the U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service in La Jolla, Calif. — have played a role in identifying three main types of killer whales in Antarctic waters and a fourth in the sub-Antarctic. The populations — likely separate species — differ in their distinctive black, white, and gray patterning; in the shapes of their dorsal fins and heads; in their geographic range; and in their food and foraging habits. Each individual has unique markings on the saddle behind the dorsal fin, and Pitman and Durban — who have amassed a collection of 40,000 photos of killer whales from Antarctic waters — have gotten to the point where they can recognize individuals and extended families.

But what has driven the men to pursue killer whale research is not the minutiae of markings or migration routes, but rather the extraordinary culture and habits of these cetaceans, whose cooperative hunting behavior and intergenerational transmission of knowledge is rivaled only by humans, Durban and Pitman contend.

Click to enlarge

As many as four generations of killer whales will travel together, passing on astonishingly sophisticated group hunting behavior from one generation to the next.

“You’ve got individuals that are spending 50, 60, 80 years together, and you can do a lot of things when you’re spending a lot of time with your family and related individuals,” Pitman told me in an interview. “You can hunt cooperatively. You can make sacrifices that other animals wouldn’t make. If you kill 50,000 seals in your lifetime, you get pretty good at it. And if you learn a few things you pass them on to your offspring. It makes them quite remarkable and very human-like in the things they do.”

“We have grandmothers, great-grandmothers, and great-great-grandmothers traveling in groups together with younger whales, imparting cultural knowledge,” added Durban.

Three years ago, farther south along the western Antarctic Peninsula, Pitman and Durban spent three weeks observing such behavior among a group of pack ice killer whales, also known as large type-B Antarctic killer

As many as four generations of killer whales travel together, passing on cultural information from one generation to the next.whales. The men studied a hunting technique known as “wave-washing,” in which a pod of whales moves through ice floes, its members lifting their heads out of the water — a behavior known as “spy-hopping” — looking for their preferred meal: fat, fish-eating Weddell seals. Once they spotted a seal on an ice floe, the whales called in reinforcements and, two to seven abreast, swam toward the floe and washed the seal off the ice by creating a large wave with powerful strokes of their tails. Pitman and Durban then observed what they call the “butchering” of seals, with the whales first drowning the seals and then meticulously stripping off their skin to get at the choice flesh.

“It was shocking to see,” said Pitman. “You’re not used to animals doing things that are so canny.”

Pitman and Durban are now aboard the 331-foot Explorer, where they will remain until mid-February, as guests of Lindblad Expeditions and National Geographic Expeditions. As visiting scientists, they use the ship as a research platform, and even rely on passengers to help take close-up photos of the killer whales’ distinctive markings, an example of the “citizen science” that has helped identify hundreds of individual killer whales in hot spots such as Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. Pitman, 62, who has a sweeping mustache, has worked in the Antarctic for more than two decades and has studied killer whales for the past 15 years. Durban, 35, a burly Englishman with a black beard, first worked with killer whales as a 16-year-old assistant to a pioneering whale researcher in Washington state.

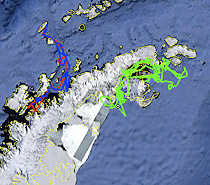

In the three weeks since the female killer whale was tagged, she and her pod have traveled many hundreds of miles in the Weddell Sea, sometimes skirting the pack ice. Durban and Pitman have tagged 15 Antarctic killer whales with the 1.4-ounce satellite transmitters over the last three years, and the results have greatly expanded knowledge of their habits, preferred habitats, and migrations. Six of the tagged type-B killer whales made rapid migrations, following a nearly identical northerly trajectory, past the Falkland Islands and beyond to the Atlantic Ocean off Brazil. One of the whales made a 6,000-mile round-trip journey from the Antarctic Peninsula to Brazilian waters and back again in just 42 days. Durban and Pitman believe the whales make these previously unknown migrations for one main purpose: shedding and renewing their skin, something they would be unable to do in frigid Antarctic waters because they would lose too much heat.

Four days after the scientists tagged the whale in the Weddell Sea, the Explorer was off the western Antarctic Peninsula, in the Gerlache Strait, a breathtaking passage flanked on both sides by glaciated mountains. There, the scientists encountered some old friends — an extended family group of roughly 70 small, type-B killer whales that spend much of their

One whale made a 6,000-mile round-trip journey from Antarctica to Brazil in just 42 days.time in the strait.

Durban and Pitman photographed nearly all of the whales, and Durban — who possesses a photographic memory for killer whale markings — recognized many of the individuals from earlier encounters. Durban was unable to get positioned for a tagging shot with the crossbow, but 10 days later, on the following cruise, he managed to shoot a $2,500 satellite tag, as well as a $4,500 dive-depth tag, onto two killer whales in the Gerlache Strait. The depth tag would reveal some information on feeding habits they had long been looking for.

This is the kind of work that scientists worldwide are doing as they intensify research into a marine mammal long thought of as one species but that likely, in fact, comprises several distinct species. Genetic testing, for example, shows that so-called transient, mammal-eating killer whales in the Pacific Northwest diverged from the resident, fish-eating whales a half-million years ago and should perhaps be recognized as a distinct species, despite being found now in the same waters. This is not a purely academic matter, as distinct species, evolved to live in certain regions and eat certain prey, may be more vulnerable to environmental change.

MORE FROM YALE e360

A Defender of World’s Whales Sees Only a Tenuous Recovery

Meanwhile, in Antarctica, Pitman and Durban continue to unlock mysteries of killer whales. Last week, the depth tag they affixed to a killer whale in the Gerlache Strait showed that the whales were repeatedly making deep, nighttime dives of up to 1,900 feet off the western Antarctic Peninsula, an indication — for the first time — that these whales were most likely eating fish and squid on or near the sea floor.