15 Jul 2010

Tracking the Himalaya’s Melting Glaciers

by david breashears

For those who know the Himalaya well — I have climbed to the summit of Mount Everest five times in the past three decades — the warming of this great mountain chain is something that we have come to experience personally. The Sherpas who live atop “the roof of the world” and the climbers who often return are acutely aware of how much temperatures have risen at high altitudes in recent years, and how extensively the snow and ice on the massive Himalayan glaciers has thinned and retreated.

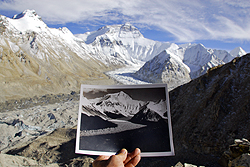

But it wasn’t until 2007, when I went back to Everest as part of a documentary for the Public Broadcasting Service series, Frontline, that I fully grasped the magnitude of the melting in this region, often called “The Third Pole” because of the massive volumes of ice in the Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau. Trekking in Tibet, not far from the northern slope of Mount Everest, I carried with me a black-and-white photograph taken by the great English mountaineer, George L. Mallory, in 1921. It showed the ice-encrusted north face of Everest and, below it, the great river of ice known as the Main Rongbuk Glacier, flowing in a sweeping, S-shaped curve down a broad, stony valley.

Eighty-six years after Mallory took that photograph, I sat in the exact spot where he had snapped his iconic picture. Pulling out his photo, I was stunned by the changes that had swept over this region. The wide river of ice had retreated more than half a mile, leaving a field of separated ice pinnacles melting into the rocky ground. In the distance, the ice streams on Everest’s flank also had shrunk, exposing more of the mountain’s dark face.

It was at that moment I decided to proceed with the project whose results are visible in the accompanying photographs. The Glacier Research Imaging Project, which I helped found, has retraced the steps of some of the world’s greatest mountain photographers as they took pictures — many of them not previously published or displayed — over the past 110 years across the Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau. I then returned to those same vantage points and took photographs that bear witness to the rapid warming of the Himalaya and the swift retreat of its glaciers. The result is an exhibition — “Rivers of Ice: Vanishing Glaciers of the Greater Himalaya” — a collaboration with the Asia Society Center on U.S.-China Relations and now on display at the Asia Society Museum in New York through Aug. 15.

These then-and-now pictures have a powerful effect on the viewer, one that I hope will bring home the reality — and serious consequences — of global warming. Gazing at Italian photographer Vittorio Sella’s 1899 picture of the Jannu Glacier in Nepal — a huge ice tongue filling a valley — and then comparing it to my 2009 photo, in which the glacier has disappeared, creates a profound sense of unease.

And we should be uneasy. The loss of these frozen reservoirs of water will have a huge impact, as the glaciers provide seasonal flows to nearly every major river system in Asia. From the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra in South Asia, to the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in China, hundreds of millions of people are partially dependent on this vast arc of high-altitude glaciers for water. As the glaciers recede and release stored water, flows will temporarily increase. But once these ice reservoirs are spent, the water supply for a sprawling, overpopulated continent will be threatened, and the impacts on water resources and food security could be dire.

But it wasn’t until 2007, when I went back to Everest as part of a documentary for the Public Broadcasting Service series, Frontline, that I fully grasped the magnitude of the melting in this region, often called “The Third Pole” because of the massive volumes of ice in the Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau. Trekking in Tibet, not far from the northern slope of Mount Everest, I carried with me a black-and-white photograph taken by the great English mountaineer, George L. Mallory, in 1921. It showed the ice-encrusted north face of Everest and, below it, the great river of ice known as the Main Rongbuk Glacier, flowing in a sweeping, S-shaped curve down a broad, stony valley.

View photo gallery

David Breashears

Near Everest in 2007, the photographer holds Mallory’s historic shot from 1921.

It was at that moment I decided to proceed with the project whose results are visible in the accompanying photographs. The Glacier Research Imaging Project, which I helped found, has retraced the steps of some of the world’s greatest mountain photographers as they took pictures — many of them not previously published or displayed — over the past 110 years across the Himalaya and the Tibetan Plateau. I then returned to those same vantage points and took photographs that bear witness to the rapid warming of the Himalaya and the swift retreat of its glaciers. The result is an exhibition — “Rivers of Ice: Vanishing Glaciers of the Greater Himalaya” — a collaboration with the Asia Society Center on U.S.-China Relations and now on display at the Asia Society Museum in New York through Aug. 15.

These then-and-now pictures have a powerful effect on the viewer, one that I hope will bring home the reality — and serious consequences — of global warming. Gazing at Italian photographer Vittorio Sella’s 1899 picture of the Jannu Glacier in Nepal — a huge ice tongue filling a valley — and then comparing it to my 2009 photo, in which the glacier has disappeared, creates a profound sense of unease.

And we should be uneasy. The loss of these frozen reservoirs of water will have a huge impact, as the glaciers provide seasonal flows to nearly every major river system in Asia. From the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra in South Asia, to the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers in China, hundreds of millions of people are partially dependent on this vast arc of high-altitude glaciers for water. As the glaciers recede and release stored water, flows will temporarily increase. But once these ice reservoirs are spent, the water supply for a sprawling, overpopulated continent will be threatened, and the impacts on water resources and food security could be dire.

View an interactive panorama of the West Rongbuk glacier

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHORDavid Breashears is a mountaineer, photographer, and filmmaker who has reached the summit of Mount Everest five times and has produced more than 40 film projects, including “Storm Over Everest.” The winner of four Emmy Awards, he co-directed and co-produced the first IMAX film shot on Everest in 1996. A year later, he performed the first live audio webcast from Everest’s summit for the PBS series NOVA. He is a Senior Fellow at the Asia Society Center on U.S.-China Relations.