A year ago, it appeared that the once-promising and environmentally risky prospects for exploitation of new shipping routes through the Arctic Ocean were waning because of low oil prices, high insurance costs, and dangerous ice conditions that persist even though climate change is rapidly melting away sea ice.

Only 17 vessels sailed through Canada’s Northwest Passage in 2014, due in part to a short and very cold summer. Ships sailing through the Northern Sea Route, or Northeast Passage — across the top of Russia and Siberia — fell from a high of 71 in 2013 to just 18 in 2015. The future fate of Arctic shipping suffered another setback with the closure of Canada’s only Arctic port at Churchill last summer.

“There was a flash of enthusiasm when shipping levels reached a peak in 2013, but they dropped from there because of low oil prices, as well as insurance and safety considerations,” says Hugh Stephens, an executive fellow at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy who published a paper on Arctic shipping earlier this year.

It is now becoming clear that interest in Arctic shipping never really faded, as a host of countries— including Russia, China, Iceland, Canada, and the United States — continue to make preparations to turn the rapidly warming Arctic into a busy global shipping route.

“Having read the research reports and talked to shipping experts from Maersk and other big shipping companies, I was sure that a route through the Arctic was going nowhere,” says Rob Huebert, an associate political science professor at the University of Calgary and a former member of Canada’s Polar Commission. But Huebert said that after listening to the Chinese and other experts talking about the prospects at the fourth annual Arctic Circle Assembly in Iceland last month, “I realized that Arctic shipping is coming, and that it is, in some ways, already here. The Chinese are taking the long view and they’re building ships, icebreakers, and ports to capitalize on the future, which may not be as far off as many think.”

The Chinese government and its state-run shipping company are touting trans-Arctic shipping routes as a pivotal development that will boost the country’s export-driven economy. At the Arctic Circle conference, the Chinese revealed that this summer five of their ships traveled along the Northern Sea Route through Arctic Russia. Ding Nong, executive vice president of the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) — which is state-run and owns 1,110 vessels — expressed confidence that many more transits through the Arctic will follow.

“As the climate becomes warmer and polar ice melts faster, the Northeast Passage has appeared as a new trunk route connecting Asia and Europe,” he said. “COSCO Shipping is optimistic about the future of the Northern Sea Route and Arctic shipping.”

An Arctic shipping boom could lead to a disaster such as the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska, scientists and indigenous communities contend.

Russia has created a single enterprise to oversee the country’s expanding economic activities in the Arctic Ocean. And in addition to longstanding Arctic ports such as Murmansk, Russia is building new Arctic shipping facilities, such as a liquid natural gas port at Sabetta on the Yamal Peninsula. Russia now has 11 Arctic ports of varying sizes.

Iceland, in an attempt to capitalize on the traffic that might come to the polar regions, is completing a two-year feasibility study for a deepwater port at Finnafjörður on the northeastern tip of the country. And in the U.S., the state of Maine is working on plans to transform Portland into an Arctic hub.

“Commercial opportunities potentially abound,” says Sen. Angus King of Maine, who is one of the main drivers behind an Arctic port in Portland, the site of this year’s Arctic Council meeting — the first time it’s been staged outside of an Arctic country or Washington D.C. “It’s 10 days shorter from Asia to Europe through the Arctic than through the Panama Canal. And the first port on the [U.S.] East Coast for ships coming from Asia is Maine.”

Experts say that opening up the Arctic to shipping on a large scale could have profound environmental consequences. Scientists and indigenous communities contend that in the absence of good governance, detailed navigation charts, sufficient ports, effective oil spill cleanup technology, and timely search and rescue responses, an Arctic shipping boom could lead to a catastrophe such as the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska. That disaster continues to have environmental impacts more than a quarter of a century later, and experts note that cleaning up an oil spill in waters partially covered by ice would be more complex than cleaning up the Exxon Valdez. Scientists also worry that noise from Arctic ships could put marine mammals such as narwhal, beluga, bowheads, and polar bears in harm’s way or drive them off traditional hunting grounds.

Despite the environmental and logistical challenges, international cargo companies are watching with interest.

“China and Russia have been working hard to take advantage of Arctic shipping,” says Jared Vineyard of Los Angeles-based Universal Cargo, which specializes in international shipping and logistics. “The aspirations of these countries to control and monetize Arctic routes are clear. Between Russia using their geographical advantage to claim control of the entire Northern Sea Route portion of the Northeast Passage and China already cutting through ice to send commercial ships through the Arctic, the U.S. could quickly be on the outside looking in. We’re keeping an eye on how this is unfolding.”

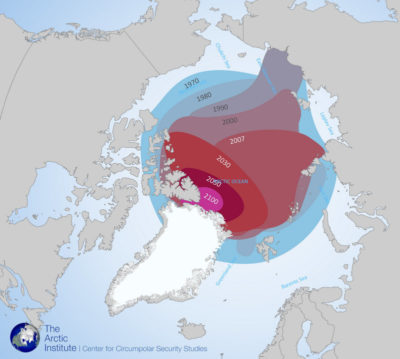

Various shipping routes that are opening up to cargo ships as warming global temperatures reduce Arctic summer sea ice. The Arctic Institute

Russia is farther ahead than any other country in exploiting Arctic shipping opportunities. It has more icebreakers by far than any other nation — 40 — and more Arctic ports. (Canada and the United States have no significant ports on the Arctic Ocean.)

To further boost the development of new shipping routes, Russia’s State Commission on Development of the Arctic Regions convened in Moscow last April to establish a single company that will oversee all logistical operations in the Arctic region and coordinate the activities of various levels of government.

Vladislav Inozemtsev, a Russian economist and director and founder of the Center for Post-Industrial Studies in Moscow, recently described Russian investment in the region as a “money-losing… Soviet-style undertaking” that will cost tens of billions of dollars in local infrastructure upgrades. He thinks it will ultimately fail because the Russians will have to charge exorbitant fees to transiting ships to recover costs of the icebreakers and port facilities, which could drive shipping traffic to routes outside of Russia’s territorial waters. These include the Northwest Passage across Arctic Canada and the Transpolar Route, which would take ships directly across the North Pole.

Says Scott Stephenson, a geographer at the University of Connecticut who has studied Arctic shipping, “I’d be interested to see how the Russians would react if the Transpolar Route became a viable one, as it might. This part of the Arctic belongs to no one. Ships that pass along this route would avoid having to pay those fees or follow the rules. Russia’s big investment in icebreakers, ports, and infrastructure would be threatened.”

In spite of all the speculation about sea ice retreat leading to a shipping boom in the Arctic, few researchers have pulled together the scientific evidence and climate modeling to determine where, and when, shipping companies could exploit the region on a large scale. Last year, Stephenson, in collaboration with geographer Laurence C. Smith of the University of California, Los Angeles, used 10 climate models — known to reasonably predict Arctic sea ice and weather — to assess shipping routes during two time periods: From 2011 to 2035, and 2036 to 2060.

“It was clear to us that the Northern Sea Route along the Russian coast will become accessible much sooner than the Northwest Passage,” says Stephenson. “But we were surprised to find that a couple of the models illustrated very clearly that the Northwest Passage would be accessible.”

Arctic summer sea ice extent, based on historical satellite records and climate modeling through 2100. The Arctic Institute

The Northwest Passage has always been the most challenging route for shipping because the Canadian Arctic Archipelago shields sea ice from the summer breakup and the melting effects of wind and powerful currents. The route through the Northwest Passage is also shallow and poorly charted. Still, the Nordic Orion, a Danish bulk carrier, saved $200,000 and four days’ transit time by shipping 15,000 metric tons of coal from Vancouver to Finland via the Northwest Passage in 2013.

It is those kinds of savings in time and money that make the Northwest Passage so appealing to countries like China, which in April published a lengthy handbook, Guidance on Arctic Navigation on the Northwest Route. The guide was designed to assist Chinese shipping companies that could soon be using this northern route as a shortcut from the Pacific to Europe or the U.S. eastern seaboard.

When asked about the guidebook by the Canadian media, Liu Pengfei, a Chinese government spokesperson, said: “Once this route is commonly used, it will directly change global maritime transport and have a profound influence on international trade, the world economy, capital flow, and resource exploitation.”

From a geopolitical point of view, Stephenson believes the Transpolar Route is the one to watch. In 2012, the Chinese Icebreaker Snow Dragon successfully sailed this route across the central Arctic Ocean.

Both Canada and Russia are expected to charge shipping companies fees for icebreaking services and passage rights when they sail through the Northwest Passage or Northern Sea Route. Shipping companies will also be obliged to abide by the environmental regulations those countries have in place.

Meanwhile, as preparations for commercial shipping intensify, cruise ships — such as the Crystal Serenity, which sailed through the Northwest Passage this summer with 1,700 people aboard — are poised to exploit the world’s unending fascination with polar bears, beluga whales, sea birds, icebergs, and glaciers. The number or passengers sailing on Arctic cruise ships has risen rapidly over the past decade. In 2005, only 11 tourism ships carrying 1,045 passengers traveled in Arctic Canada, according to statistics compiled by the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators. In 2015, 40 ships and more than 3,600 passengers made Canadian Arctic voyages.

Frigg Jørgensen, executive director of the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators, expects cruise traffic will also grow in Iceland, Norway, and Greenland. At the other end of the earth, in Antarctica, more than 36,000 tourists visited the continent in 2014-2015, nearly all on cruise ships. Some vessels have occasionally run aground or sunk in Antarctica, though so far without major oil spills or other environmental damage.

In addition to oil spills and impacts on marine mammals, scientists and environmentalists are concerned that the black carbon emitted by combustion of the heavy oil used by big ships will accelerate sea ice retreat, as the dark soot settles on ice and snow and absorbs heat.

Scott Highleyman, who oversees Arctic marine campaigns for The Pew Charitable Trusts, says that ice data, wildlife migration routes, wildlife habitat, and subsistence indigenous activities have yet to be incorporated into shipping corridor designs. Jackie Dawson, a geographer and environmental scientist at the University of Ottowa, is now working with Canadian Inuit communities to develop a digitized map that will identify marine environments that are both ecologically and culturally important. This could be used to develop “no go” or “slow go” zones for ships at different times of the year.

Vladimir Mednikov, president of the Russian Maritime Law Association, and Henry Huntington, senior officer and science director for Arctic Ocean projects at the Pew Charitable Trusts, said in a recent article that many of the pitfalls can be avoided if there is good governance and a better understanding of the impacts of Arctic shipping. What is needed, Huntington and Mednikov wrote, is sound planning, effective rules, and good communication among all involved parties. They say that the International Maritime Organization’s Polar Code, which goes into effect on January 1, 2017, is a good start. But they argue that the regulations relating to ship structure, stability, communications, and oil spill planning does not go far enough.

“There is the potential, as in any human endeavor, for things to go wrong in Arctic shipping,” Huntington said in an email exchange. “But there also is a great deal of incentive for things to go right. Good governance can reduce risks and create opportunities. If Arctic shipping expands with little oversight or coordination, business, environment, and local communities are all likely to suffer.”