The Alberta tar sands industry — and the governments that depend on tar sands tax revenues — are facing an increasingly pressing problem: How to get the growing flow of oil sands bitumen to market. And with proposed pipelines to the south, east, and west facing stiff opposition, tar sands interests are now investigating another controversial option — heading north and shipping their product via the Arctic.

To the south, the proposed $10 billion Keystone XL pipeline, which would transport Alberta tar sands oil through the heartland of the U.S. to refineries on the Gulf of Mexico, faces the possibility of being killed by the Obama administration later this year. Two pipeline proposals that would ship processed bitumen from Alberta’s tar sands to Canada’s Pacific Coast have been stalled by aboriginal, municipal, and environmental interests, who fear spills in environmentally sensitive mountain and coastal environments. A third project — Trans Canada’s Energy East Pipeline proposal, which would send Alberta oil to Atlantic Canada — has encountered such strong resistance that the pipeline company last week announced a two-year delay in its plans.

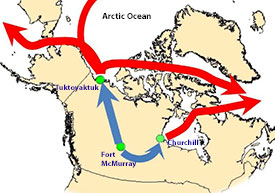

These setbacks have led to the revival of an old idea by oil interests and the governments of Alberta and the Northwest Territories: Sending Canadian oil north through a so-called “Arctic Gateway.” One possible pipeline route would run from Alberta, through Saskatchewan and Manitoba, to the port of Churchill along the west coast of Hudson Bay. From there the oil would travel by tanker through the increasingly ice-free Arctic Ocean to the Atlantic or Pacific oceans. Another possible route would follow the Mackenzie River Valley to the hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk on the Arctic Ocean and on to the Pacific.

“Alberta can play a leading role in the opening of the Northwest Passage,” says a 2013 report by Canatec Associates International that was commissioned by the Alberta provincial government and is now attracting renewed attention. “This will be a revolution in global logistics, equal in impact to the opening of the Suez or Panama canals.”

Far-fetched as these alternatives seem to be during this time of low oil prices, the Arctic Gateway concept has nevertheless been getting a surprising amount of government attention, if only because no one seems to be able to get a tar sands pipeline built elsewhere. A spokesman for Alberta Energy Minister Frank Oberle said the province “is actively pursuing the Arctic Gateway idea.” Northwest Territories Premier Bob McLeod said recently that an Arctic-bound oil pipeline along the Mackenzie Valley would be vital to helping the territories tap into an estimated 10 billion barrels of oil and 92 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

Alberta is counting on the steady growth of tar sands production to boost flagging oil tax revenues.

The search for new routes to send oil sands bitumen to market is critical for the Alberta tar sands oil industry, which is planning to triple production from 1.5 million barrels a day currently to 4.5 million barrels a day by 2030. And the Alberta and Canadian governments also are counting on the steady growth of tar sands production to boost tax revenues.

The recent collapse in oil prices has left the Alberta government, in particular, facing severe budget shortfalls. A leading Canadian bank has estimated that Alberta could lose $7 billion in revenue in 2015 if oil sells at $70 a barrel — significantly higher than current prices. In March, Alberta did the unthinkable by raising income taxes and user and license fees across the board, as well as making spending cuts to almost every government service. Even with that, the province faces a staggering $5 billion budgetary shortfall for the coming year.

Meanwhile, the Canadian government, which could lose $5 billion or more in oil revenue in 2015, has taken the unusual step of delaying its annual budget plan until the fallout from oil’s collapse can be better assessed.

“If the Arctic Gateway proposal succeeds, it would be reasonable to assume that oil sands production would expand significantly from current levels,” said Victoria Herrmann, a Gates Cambridge Scholar who is associated with the Center for Circumpolar Security Studies at the Washington D.C-based Arctic Institute. “Currently, the pipeline capacity to transport the level of crude oil Alberta wants to produce to refineries is non-existent. If Canada wants to fulfill its planned expansion [of the tar sands] it will need the infrastructure to transport the petroleum to the global energy market. Without some means of getting the bitumen out of Alberta, oil sands production stands to face a serious decline.”

Many energy experts are skeptical that any version of an Arctic Gateway route for oil export will see the light of day. They say that the Arctic pipeline proposals reflect rising worries in the tar sands industry about getting its bitumen to market.

“I can’t imagine there’s enough value in a barrel of bitumen to make any of this worth doing,” says Andrew Leach, a University of Alberta energy expert. “If you think about bitumen being worth about $50 per barrel at today’s prices, to dilute it and ship it through that kind of infrastructure to get it to market is unlikely to make producing it worthwhile. I can’t see it as economically feasible.”

Many energy experts are skeptical that an Arctic Gateway route for oil will see the light of day.

Doug Matthews, the former director of oil and gas in the Northwest Territories, agrees. He is especially skeptical of a proposal to initially ship the bitumen down the Mackenzie Valley by rail, then by barge to the Arctic coast before it is loaded offshore onto tankers. (If Arctic shipping proved feasible, the railways cars and barges would eventually be replaced by a pipeline.)

“The bitumen would have to be handled three times, and then a way would have to be found to store it for several months during the winter season,” he said.

Government and industry, however, may see no other alternatives if Keystone XL and the major Canadian pipeline proposals fail to get back on track.

A little less than a year ago, most experts were confident that a way would eventually be found to get Alberta’s bitumen to market, in spite of the fierce opposition to Keystone XL and other pipelines. Far too much was at stake, they reasoned, to allow one or more of the pipelines to fail.

The lack of access to pipeline capacity has already persuaded energy companies such as Statoil to back off on multi-billion dollar investments in the tar sands. “Costs for labor and materials have continued to rise in recent years and are working against the economics of new projects,” said Statoil Canada’s StÃ¥le Tungesvik, explaining why the company in November delayed for three years its Corner project in Alberta, projected to produce 40,000 barrels of oil a day. “Market access issues also play a role — including limited pipeline access, which weighs on prices for Alberta oil.”

Lack of access to pipeline capacity has persuaded energy companies to back off major investments.

Statoil’s announcement came just months after Total and Suncor Energy Inc. indefinitely put on hold their $11 billion Joslyn North oil sands project, which would have produced 160,000 barrels a day by 2020.

Lack of pipeline capacity is one reason why Alberta has invested in two studies that consider the feasibility of an Arctic Gateway route for tar sands oil. According to the 2013 report done by Canatec Associates, climate change is quickly melting the sea ice that had previously made shipping oil through the Arctic impossible. The authors of the report also note that “an aggressive push from the Canadian government to reduce environmental oversight” in the Arctic makes the proposal much more viable.

The report’s authors outline several scenarios in which Alberta’s bitumen might move north along pipelines to the west coast of Hudson Bay, or via the Mackenzie Valley to the coastal town of Tuktoyaktuk by pipeline or train, barge, and tanker. The appeal of the Tuktoyaktuk project is that Canada’s National Energy Board has already approved that route for a different pipeline project, which is in limbo. All but one of the aboriginal groups in the Mackenzie Valley supported the earlier project, which would have given them a one-third stake in the venture.

ALSO FROM YALE e360Shipping Crude Oil by Rail: New Front in Tar Sands Wars

Another report, commissioned by the Alberta government and scheduled for release this spring, will evaluate the feasibility of a plan to build a railroad from northern Alberta through British Columbia and the Yukon to Valdez, Alaska, where bitumen would be shipped to overseas markets.

The proposed 2,400-kilometer railroad was once the dream of former Alaska Senator Frank Murkowski, who was behind the “Rail to Resources” legislation passed by the U.S. Congress in 2000. This latest idea is the brainchild of a Vancouver-based business consortium that calls itself Generating for Seven Generations.

These various proposals represent an important shift in attitude among energy interests and government officials in Canada. Once unthinkable, a

steep decline for the tar sands industry is no longer a totally outlandish idea, even to boosters such as Terence Corcoran, editor of Canada’s Financial Post section of the Toronto-based National Post newspaper. In a recent column he predicted that the failure to get a pipeline built from Alberta’s tar sands might result in “the end to Canada’s oil superpower pipe dreams.”