Loose pipe flanges. Leaky storage tanks. Condenser valves stuck open. Outdated compressors. Inefficient pneumatic systems. Corroded pipes.

Forty separate types of equipment are known to be potential sources of methane emissions during the production and processing of natural gas and oil by hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, of underground shale formations. As the fracking boom continues unabated across the U.S., scientists, engineers, and government experts are increasingly focusing on the complex task of identifying the sources of these methane leaks and devising methods to stop them.

“There are many, many, many possible leaking sources,” said Adam Brandt, a Stanford University professor of energy resources engineering who compiled recent estimates of the oil and gas industry’s methane emissions. “Just like a car, there are a variety of ways it can break down.”

Even among industry officials, there is agreement that getting control of methane emissions is an important issue. At heart it is an engineering problem, and solutions from government, industry, and academia are beginning to take shape. Analysts say that battling the problem must occur on two closely related fronts: tighter regulations at the state and federal level, and a commitment from industry to make the large investment necessary to stanch the leaks.

Last month, the Obama administration announced a plan to reduce methane emissions from a host of sources, including landfills, cattle, and the oil and gas industry. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has pledged to identify approaches to cut so-called “fugitive” methane emissions from oil and gas drilling by this fall and to issue new rules by 2016 as President Obama’s term in office comes to an end. Roughly nine percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions come from methane.

“The strategy is a good plan of action,” said Vignesh Gowrishankar, a staff scientist at Natural Resources Defense Council. “But more needs to be done. The most important thing is to ensure that EPA implements stronger standards that go after methane directly and include existing equipment in the field because that is what is leaking.”

Colorado, a major oil and gas producer, in February became the first state to impose regulations requiring producers to find and fix methane leaks. And as public concerns mount over the environmental fallout from the fracking boom, even states such as Texas are examining whether to adopt tighter methane regulations.

Industry has lived with methane leaks, despite the value of capturing and eventually selling the methane, because of the expense involved in stopping fugitive emissions. Fixing the problem would require a comprehensive approach that would involve not only detecting methane leaks, but also instituting a host of engineering and mechanical fixes along the entire chain of production and processing, from the wellhead to pipes.

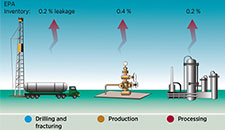

Solving the problem would require a host of fixes along the entire production chain.

Reducing fugitive methane emissions can be classified into easy fixes, such as tightening pipe flanges, to harder ones such as replacing valves in compressor stations that constantly pump gas under intense pressure, said Bryan Willson, program director at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E).

There is less incentive for the industry — particularly smaller, cash-constrained companies — to make fixes that require more personnel, time, and money, yielding a lower return-on-investment. Some of the fixes, such as “vapor recovery units” that prevent gas from volatilizing from storage tanks, come with a price tag of $100,000 each, said Gowrishankar. One study found storage tanks to be a significant source of volatile organic compounds and methane emissions in Texas’ Barnett Shale region.

A key question is whether the U.S. can achieve a significant reduction in methane emissions as the fracking boom continues to expand and older equipment becomes more prone to problems. With close to 500,000 hydraulically fractured gas wells alone and hundreds of thousands of miles of pipelines, just figuring out the scope of the problem, let alone fixing all the leaks, is a daunting challenge, experts say.

Calculating exactly how much methane is escaping during the fracking and processing of oil and gas is exceedingly difficult. Estimates of methane emissions range from 1.5 percent to 9 percent. Getting a clearer sense of the scope of the problem is vital; although methane only lingers in the atmosphere for 10 to 20 years — as opposed to hundreds of years for carbon dioxide — recent studies show that methane is 34 times as potent a greenhouse gas as CO2. Failing to stop widespread methane leaks from the global oil and gas industry in the coming decades could significantly exacerbate global warming, many experts say.

A study found leaks of methane from drilling sites were 50 percent higher than previously estimated.

With an expected 56-percent increase over the next 25 years in U.S. natural gas production alone — most of which is expected to come from fracking — the problem of methane leaks is going to get worse “unless we make the investment” in lower-emissions technology, said Michael Obeiter, a senior associate in the climate and energy program at the World Resources Institute.

In February, Brandt and 15 co-authors published a paper in Science, based on a review of more than 200 previous studies, concluding that leaks of methane from drilling sites were 50 percent higher than previously estimated by the EPA. “A variety of evidence” points to emissions higher than 1.5 percent, Brandt said.

Environmental groups such as the World Resources Institute, Environmental Defense Fund, and the Natural Resources Defense Council say a mix of regulation and new technology in detection and emission-control engineering could push the industry to address the problem of leaks.

Methane emissions from oil and gas drilling are broken down into two different problem areas. The first is outdated equipment that emits much more methane than newer, low-emissions technology. The second is a string of leaks in the system, many which can be difficult to detect. “If we can develop a way to find these leaks cheaply, frequently, and in an automated fashion,” most of the leaks can be detected and fixed, said Brandt.

Obeiter lists two major equipment upgrades that have already shown promise in the field, but have not been widely adopted by industry.

The first is the use of plunger lift systems at new and existing wells during “liquids unloading,” which are operations that clear water and other liquids from the system. The second is replacing existing high-bleed pneumatic devices with low-bleed equivalents throughout natural gas systems.

Some companies such as Encana — a natural gas producer that has 4,000 gas wells in Colorado — are retrofitting outdated equipment prone to leaking, and installing technology to capture leaks at the wellhead. The company began replacing existing high-bleed pneumatic devices before the conversion was mandated in Colorado’s new regulations, said Doug Hock, a spokesman for the company. Hock calls the new rules in Colorado “tough but reasonable” and says they provide the industry in the state with regulatory certainty going forward.

But even if every state mirrored Colorado and every oil and gas company took steps such as Encana is taking, a significant amount of methane would still be leaking — and much of it undetected, says Mark Zondlo, a professor of engineering at Princeton University. That’s because many methane leaks are caused by more erratic and episodic factors, such as a valve or storage-tank hatch suddenly stuck open. Hence the need for “continuous measurements” for methane leaks across large areas, Zondlo said.

There is a lot of guessing by industry about where and how often leaks occur, an expert says.

Currently, there is a lot of “guessing” on the part of the industry and researchers as to where and how frequently the majority of leaks are happening, says Zondlo.

Industry representatives say the methane leakage rate is at the low end of estimates, about 1.5 percent, placing industry second behind emissions attributed to livestock, said Katie Brown, spokesperson for Energy in Depth, a program of the Independent Petroleum Association of America.

To achieve climate benefits from natural gas, environmental groups estimate the leakage rate during gas drilling must remain below 1 percent. “Cutting methane leakage rates from natural gas systems to less than 1 percent of total production would ensure that the climate impacts of natural gas are lower than coal or diesel fuel over any time horizon,” Obeiter said.

But Sandra Steingraber, an environmentalist and scholar in residence at Ithaca College, compares chasing methane leaks and retrofitting old equipment to “putting filters on cigarettes.” She said that even reducing methane leaks by 30 to 40 percent will be too little too late to help slow climate change, especially as the industry expands.

Currently, many companies are using methane-leak detection tools, such as infrared cameras, that are too labor-intensive and fail to find many leaks. What’s needed, say Obeiter and other experts, is an industry-wide method for monitoring and repairing methane leaks across the production and processing system.

Zondlo recently developed a methane sensor mounted on a remote—controlled aircraft built at the University of Texas at Dallas. In October, the aircraft was used to quantify emission rates from well pads and a compressor station in the Barnett Shale region. Zondlo has been partnering with other groups that fly drones over fracking areas to detect leaks.

Robert B. Jackson, an ecologist and energy expert at Duke University, also has been testing drones to detect fugitive methane emissions. The main drawback, he says, is the payload. “Carrying a big camera or methane sensor, a drone might be able to stay in the air for 30 minutes,” says Jackson. “It’s difficult to screen a shale play with that kind of time.”

Engineers are trying to develop lighter sensors that will allow drones to stay in the air longer. “I’m very bullish long-term on using drones to measure leaks,” Jackson said. “Are we there yet right now? No.”

In the Pinedale Anticline natural gas field in Wyoming, Shane Murphy and Robert Field of the University of Wyoming recently outfitted a Mercedes Sprinter van with a mass spectrometer and other high-powered scientific instruments to measure volatile organic compounds and methane. When combined with meteorological instrumentation and sophisticated software, these technologies can detect methane plumes and quantify emission rates from specific sources — all from inside the van. The equipment records readings every half-second, which allows it to be used on the move. “This approach can cover a lot of ground,” Field said.