“We are now in this regime where we are doing something new to the atmosphere that hasn’t been done before,” a scientist says.

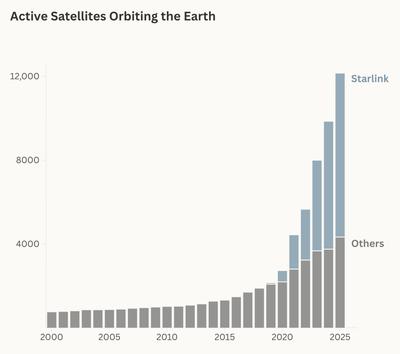

Starlink has sought permission from the Federal Communications Commission to expand its swarm, which at this point comprises the vast majority of Earth’s active satellites, so that it might within a few years have as many as 42,000 units in orbit. Blue Origin, the rocket company led by Jeff Bezos, is in the early stages of helping to deploy a satellite network for Amazon, a constellation of about 3,000 units known as Amazon Leo. European companies, such as France’s Eutelsat, plan to expand space-based networks, too.

“We’re now at 12,000 active satellites, and it was 1,200 a decade ago, so it’s just incredible,” Jonathan MacDowell, a scientist at Harvard and the Smithsonian who has been tracking space launches for several decades, told me recently. MacDowell notes that based on applications to communications agencies, as well as on corporate projections, the satellite business will continue to grow at an extraordinary rate. By 2040, it’s conceivable that more than 100,000 active satellites would be circling Earth.

But counting the number of launches and satellites has so far proven easier than measuring their impacts. For the past decade, astronomers have been calling attention to whether so much activity high above might compromise their opportunities to study distant objects in the night sky. At the same time, other scientists have concentrated on the physical dangers. Several studies project a growing likelihood of collisions and space debris — debris that could rain down on Earth or, in rare cases, on cruising airplanes.

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket at takeoff. SpaceX now has more than 9,000 Starlink satellites orbiting the Earth. SpaceX

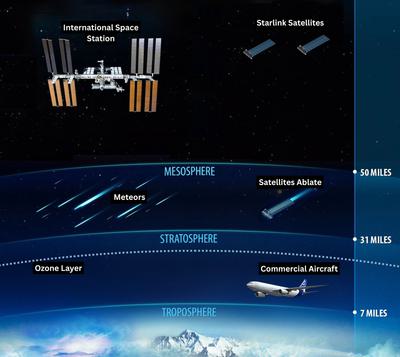

More recently, however, scientists have become alarmed by two other potential problems: the emissions from rocket fuels, and the emissions from satellites and rocket stages that mostly ablate (that is, burn up) on reentry. “Both of these processes are producing pollutants that are being injected into just about every layer of the atmosphere,” explains Eloise Marais, an atmospheric scientist at University College London, who compiles emissions data on launches and reentries.

As Marais told me, it’s crucial to understand that Starlink’s satellites, as well as those of other commercial ventures, don’t stay up indefinitely. With a lifetime usefulness of about five years, they are regularly deorbited and replaced by others. The new satellite business thus has a cyclical quality: launch; deploy; deorbit; destroy. And then repeat.

The cycle suggests we are using Earth’s mesosphere and stratosphere — the layers above the surface-hugging troposphere — as an incinerator dump for space machinery. Or as Jonathan MacDowell puts it: “We are now in this regime where we are doing something new to the atmosphere that hasn’t been done before.” MacDowell and some of his colleagues seem to agree that we don’t yet understand how — or how much — the reentries and launches will alter the air. As a result, we’re unsure what the impacts may be to Earth’s weather, climate, and (ultimately) its inhabitants.

A satellite component burns up in a wind tunnel as part of a test to understand how it would disintegrate upon reentering the atmosphere. European Space Agency

To consider low-Earth orbit within an emerging environmental framework, it helps to see it as an interrelated system of cause and effect. As with any system, trying to address one problematic issue might lead to another. A long-held idea, for instance, has been to “design for demise,” in the argot of aerospace engineers, which means constructing a satellite with the intention it should not survive the heat of reentry. “But there’s an unforeseen consequence of your solution unless you have a grasp of how things are connected,” according to Hugh Lewis, a professor of astronautics at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. In reducing “the population of debris” with incineration, Lewis told me — and thus, with rare exceptions, saving us from encounters with falling chunks of satellites or rocket stages — we seem to have chosen “probably the most harmful solution you could get from a perspective of the atmosphere.”

We don’t understand the material composition of everything that’s burning up. Yet scientists have traced a variety of elements that are vaporizing in the mesosphere during the deorbits of satellites and derelict rocket stages; and they’ve concluded these vaporized materials — as a recent study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) put it — “condense into aerosol particles that descend into the stratosphere.” The PNAS study, done by high altitude air sampling and not by modeling, showed that these tiny particles contained aluminum, silicon, copper, lead, lithium, and more exotic elements like niobium. The large presence of aluminum, signaling the formulation of aluminum oxide nanoparticles, may be especially worrisome, since it can harm Earth’s protective ozone layers and may undo our progress in halting damage done by chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs. A recent academic study in the journal Geophysical Research Letters concluded that the ablation of a single 550-pound satellite (a new Starlink unit is larger, at about 1,800 pounds) can generate around 70 pounds of aluminum oxide nanoparticles. This floating metallic pollution may stay aloft for decades.

The PNAS study and others, moreover, suggest the human footprint on the upper atmosphere will expand, especially as the total mass of machinery being incinerated ratchets up. Several scientists I spoke with noted that they have revised their previous belief that the effects of ablating satellites would not exceed those of meteorites that naturally burn up in the atmosphere and leave metallic traces in the stratosphere. “You might have more mass from the meteoroids,” Aaron Boley, an astronomer at the University of British Columbia, said, but “these satellites can still have a huge effect because they’re so vastly different [in composition].”

Last year, a group of researchers affiliated with NASA formulated a course of research that could be followed to fill large “knowledge gaps” relating to these atmospheric effects. The team proposed a program of modeling that would be complemented by data gleaned from in situ measurements. While some of this information could be gathered through high-altitude airplane flights, sampling the highest-ranging air might require “sounding” rockets doing tests with suborbital flights. Such work is viewed as challenging and not inexpensive — but also necessary. “Unless you have the data from the field, you cannot trust your simulations too much,” Columbia University’s Kostas Tsigaridis, one of the scientists on the NASA team, told me.

It seems increasingly clear that rocket emission plumes, like reentries, will have a significant effect on the ozone layer.

Tsigaridis explains that lingering uncertainty about NASA’s future expenditures on science has slowed U.S. momentum for such research. One bright spot, however, has been overseas, where ESA, the European Space Agency, held an international workshop in September to address some of the knowledge gaps, particularly those relating to satellite ablations. The ESA meeting resulted in a commitment to begin field measurement campaigns over the next 24 months, Adam Mitchell, an engineer with the agency, said. The effort suggests a sense of urgency, in Europe, at least, that the space industry’s growth is outpacing our ability to grasp its implications.

The atmospheric pollution problem is not only about what’s raining down from above, however; it also relates to what happens as rockets go up. According to the calculations of Marais’ UCL team, the quantity of heat-trapping gases like CO2 produced during liftoffs are still tiny in comparison to, say, those of commercial airliners. On the other hand, it seems increasingly clear that rocket emission plumes from the first few minutes of a mission, which disperse into the stratosphere, may, like reentries, have a significant effect on the ozone layer.

A test flight of a SpaceX Starship. SpaceX

The most common rocket fuel right now is a highly refined kerosene known as RP-1, which is used by vehicles such as SpaceX’s Falcon 9. When RP-1 is burned in conjunction with liquid oxygen, the process releases black carbon particulates into the stratosphere. A recent study led by Christopher Maloney of the University of Colorado used computer models to assess how the black carbon absorbs solar radiation and whether it can warm the upper atmosphere significantly. Based on space industry growth projections a few decades into the future, these researchers concluded that the warming effect of black carbon would raise temperatures in the stratosphere by as much as 1.5 degrees C, leading to significant ozone reductions in the Northern Hemisphere.

It may be the case that a different propellant could alleviate potential problems. But a fix isn’t as straightforward as it seems. Solid fuels, for instance, which are often used in rocket boosters to provide additional thrust, emit chlorine — another ozone-destroying element. Meanwhile, the propellant of the future looks to be formulations of liquefied natural gas (LNG), often referred to as liquid methane. Liquid methane will be used to power SpaceX’s massive Starship, a new vehicle that’s intended to be used for satellite deployments, moon missions, and, possibly someday, treks to Mars.

SpaceX executives have said they would like to build a new Starship every day, readying for a near-constant cycle of launches.

The amount of black carbon emissions from burning LNG may be 75 percent less than from RP-1. “But the issue is that the Starship rocket is so much bigger,” UCL’s Marais says. “There’s so much more mass that’s being launched.” Thus, while liquid methane might burn cleaner, using immense quantities of it — and using it for more frequent launches — could undermine its advantages. Recently, executives at SpaceX’s Texas factory have said they would like to build a new Starship every day, readying the company for a near-constant cycle of launches.

One worry amongst scientists is that if new research suggests that space pollution is leading to serious impacts, it may eventually resemble an airborne variation of plastics in the ocean. A more optimistic view is that these are the early days of the space business, and there is still time for solutions. Some of the recent work at ESA, for instance, focuses on changing the “design for demise” paradigm for satellites to what some scientists are calling “design to survive.” Already, several firms are testing satellites that can get through an reentry without burning up; a company called Atmos, for instance, is working on an inflatable “atmospheric decelerator” that serves as a heat shield and parachute to bring cargo to Earth. Satellites might be built from safer materials, such as one tested in 2024 by Japan’s space agency, JAXA, made mostly from wood.

An inflatable heat shield developed by ATMOS Space Cargo to help return payloads safely to Earth. ATMOS Space Cargo

More ambitious plans are being discussed: Former NASA engineer Moriba Jah has outlined a design for an orbital “circular economy” that calls for “the development and operation of reusable and recyclable satellites, spacecraft, and space infrastructure.” In Jah’s vision, machines used in the space economy should be built in a modular way, so that parts can be disassembled, conserved, and reused. Anything of negligible worth would be disposed of responsibly.

Most scientists I spoke with believe that a deeper recognition of environmental responsibilities could rattle the developing structure of the space business. “Regulations often translate into additional costs,” says UCL’s Marais, “and that’s an issue, especially when you’re privatizing space.” A shift to building satellites that can survive reentry, for instance, could change the economics of an industry that, as astronomer Aaron Boley notes, has been created to resemble the disposable nature of the consumer electronics business.

Boley also warns that technical solutions are likely only one aspect of avoiding dangers and will not address all the complexities of overseeing low-Earth orbit as a shared and delicate system. It seems possible to Boley that in addition to new fuels, satellite designs, and reentry schemes, we may need to look toward quotas that require international management agreements. He acknowledges that this may seem “pie in the sky”; while there are treaties for outer space, as well as United Nations guidelines, they don’t address such governance issues. Moreover, the emphasis in most countries is on accelerating the space economy, not limiting it. And yet, Boley argues that without collective-action policy responses we may end up with orbital shells so crowded that they exceed a safe carrying capacity.

That wouldn’t be good for the environment or society — but it wouldn’t be good for the space business, either. Such concerns may be why those in the industry increasingly discuss a set of principles, supported by NASA, that are often grouped around the idea of “space sustainability.” University of Edinburgh astronomer Andrew Lawrence told me that the phrase can be used in a way that makes it unclear what we’re sustaining: “If you look at the mission statements that companies make, what they mean is, we want to sustain this rate of growth.”

But he doesn’t think we can. As one of the more eloquent academics arguing for space environmentalism, Lawrence perceives an element of unreality in the belief that in accelerating space activity we can “magically not screw everything up.” He thinks a goal in space for zero emissions, or zero impact, would be more sensible. And with recent private-sector startups suggesting that we should use space to build big data centers or increase sunlight on surface areas of Earth, he worries we are not entering an era of sustainability but a period of crisis.

Lawrence considers debates around orbital satellites a high-altitude variation on climate change and threats to biodiversity — an instance, again, of trying to seek a balance between capitalism and conservation, between growth and restraint. “Of course, it affects me and other professional astronomers and amateur astronomers particularly badly,” he concedes. “But it’s really that it just wakes you up and you think, ‘Oh, God, it’s another thing. I thought, you know — I thought we were safe.’” After a pause, he adds, “But no, we’re not.”