The world is poised to overshoot the goal of limiting average global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, as for the first time, a three-year period, ending in 2025, has breached the threshold. And climate scientists are predicting devastating consequences, just as the world’s governments appear to have lost their appetite for tackling the emissions that are causing the warming.

The 1.5-degree target was set at the Paris climate conference a decade ago, at the insistence of more vulnerable nations, to forestall severe weather impacts and potential runaway warming that could lead to exceeding irreversible planetary tipping points. But climate scientists say that 10 years of weak action since mean that nothing can now stop the target being breached. “Climate policy has failed. The 2015 landmark Paris agreement is dead,” says atmospheric chemist Robert Watson, a former chair of the U.N.’s arbiters of climate science, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Meanwhile, a picture of what lies ahead is becoming clearer. In particular, there is a growing fear that climate change in the future won’t, as it has until now, happen gradually. It will happen suddenly, as formerly stable planetary systems transgress tipping points — thresholds beyond which things cannot be put back together again.

“Nature has so far balanced our abuse,” says Johan Rockström, a leading Earth systems scientist. “This is coming to an end.”

“We are rapidly approaching multiple Earth system tipping points that could transform our world with devastating consequences for people and nature,” says British global-systems researcher Tim Lenton, of the University of Exeter. If he and other scientists are right, then hopes currently being expressed of a temperature reset by reducing emissions after overshoot may be fanciful. Before we know it, there may be no way back.

The effects of imminent 1.5-degree overshoot are already apparent in a rising tide of weather catastrophes: soaring heatstroke deaths in India, Africa, and the Middle East; unprecedented wildfires in the United States; and escalating property damage and floods from tropical storms and extreme precipitation.

Last year, Bailing Li of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center disclosed that her agency held un-peer reviewed data showing a dramatic increase in the intensity of the world’s weather in the past five years. Meanwhile, the International Chamber of Commerce reported that extreme weather linked to the changing climate had cost the global economy more than $2 trillion in the past decade and damaged the lives and livelihoods of a fifth of the world’s population.

But that is just the start. Climate change is gathering pace. The last three years have been the hottest on record, with both 2023 and 2025 nearly reaching 1.5 degrees above preindustrial levels, and 2024 hitting 1.55 degrees.

Average global temperature compared to the preindustrial average. Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service. Yale Environment 360 / Made with Flourish

A three-year breach of 1.5 degrees does not mean we have broken the Paris limit, which is framed as a long-term average. Conventionally, scientists measure this over 20 years, to smooth out year-on-year aberrations caused by natural cycles such as the El Niño oscillation. Using this method, it will be several more years before researchers can say for certain if warming has reached 1.5 degrees. But according to two studies published last year, the world has likely already surpassed this critical threshold.

Without an abrupt change of course, the warming will only accelerate. James Hansen, the Columbia University climatologist who first put climate change on the world’s front pages during testimony to Senate hearings in 1988, believes we could hit 2 degrees C as soon as 2045, a forecast based on several climate models under a high-emissions scenario.

The reason for the escalation is that the climate system is in a pincer grip. First, emissions of planet-warming gases remain stubbornly high, and second, natural carbon sinks are weakening. The result is an accelerating rise in atmospheric concentrations of CO2. 2024 saw the biggest jump ever.

The faltering natural sink is perplexing scientists. For as long as we know, nature has been quietly mitigating our damage to the climate by soaking up around half of all the CO2 we put into the air. Trees have grown faster in a warmer climate, capturing carbon in the process; oceans have been absorbing excess atmospheric CO2, burying it in the depths.

There are also fears of a domino effect, in which crossing one tipping point triggers the exceeding of another.

But now oceans are becoming more stratified, reducing their ability to remove CO2. And trees are succumbing to heat and drought.

A string of recent research papers has reported an “unprecedented” weakening of natural land-based carbon sinks in 2023 and 2024, triggered in part by an epidemic of extreme wildfires, which have doubled globally in the past two decades. African rainforests, previously responsible for around a fifth of the terrestrial take-up of CO2, recently turned from a long-term carbon sink to a source.

Looking forward, the predicted death of the Amazon rainforest would load billions of tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. And the melting of Arctic permafrost, which is already underway, will unlock huge volumes of frozen methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Researchers last year concluded that this methane will have a “critical role… in amplifying climate change under overshoot scenarios,” making a comeback from that overshoot significantly harder.

“We are seeing cracks in the resilience of the Earth’s systems,” concluded Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research. “Nature has so far balanced our abuse. This is coming to an end.”

A woman keeps vigil on a man who suffered heatstroke during a 2024 heat wave in Varanasi, India. Indranil Aditya / NurPhoto via Getty Images

These escalating impacts could soon lead to irreversible damage to the climate and ecosystems, scientists warn. In the past three years, unprecedented warming of the oceans has led to an epidemic of marine heat waves. The waters of northwest Europe last spring were up to 4 degrees C (7 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than normal. In the tropics, ocean heating is triggering a rising rate of cyclones, and ever more loss of coral.

Researchers say tropical coral reefs may have already crossed a tipping point, portending mass dieback. Studies suggest they may all be dead by mid-century, with massive repercussions for wider marine ecosystems and fish stocks, which are heavily dependent on reefs as nurseries and feeding grounds.

Near the poles, some ice sheets may already have been irreversibly destabilized. Greenland is losing 30 million tons of ice every hour. The “current best assessment,” Watson says, is that this melting could become unstoppable at around 1.5 degrees. The giant Arctic island’s estimated 2,800 trillion tons of ice would take centuries to melt into the ocean. But that would eventually raise sea levels globally by around 23 feet. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet faces a similar fate.

Because tipping points are hard to model with any precision, they are often left out of climate projections.

Likewise, ocean circulation systems could be approaching breakdown. These currents move vast amounts of heat around the globe, dictating much of the weather over adjacent land. Most at risk, modelers suggest, is the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), which currently warms Europe and the eastern coast of North America with the Gulf Stream.

Hansen has argued that “shutdown of the AMOC is likely within the next 20-30 years, unless actions are taken to reduce global warming.” Other studies suggest it is unlikely this century, or that we may soon pass a tipping point beyond which it is inevitable. A 2025 Global Tipping Points Report, led by Lenton, said AMOC’s failure would “plunge northwest Europe into prolonged severe winters.”

A modeling study of a range of potential tipping points by researchers at the Potsdam Institute found that if the world did not get back to 1.5 degrees by the end of the century, there was a one in four chance at least one major global threshold — it listed the collapse of AMOC, the Amazon rainforest ecosystem, or the Greenland or West Antarctic ice sheet — would be crossed. “If we were to also surpass 2 degrees C of global warming, tipping risks would escalate even more rapidly,” says coauthor Annika Ernest Högner.

There are also fears of a domino effect, in which crossing one tipping point triggers the exceeding of another. One scenario sees the melting of Greenland ice turning off the AMOC, which in turn is the final straw for the Amazon rainforest. But much remains unclear — including whether the risks of exceeding tipping points are less if the overshoot is short term.

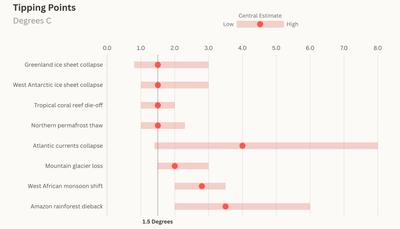

Estimated temperature increases at which the planet crosses key tipping points. Source: Armstrong McKay et al., 2022. Yale Environment 360 / Made with Flourish

Because tipping points are hard to model with any precision, and harder still to predict, they are often left out of climate projections — and hence are still largely ignored by climate negotiators. “Current policy thinking doesn’t usually take tipping points into account,” says Manjana Milkoreit of the University of Oslo, a lead author of the 2025 Global Tipping Points Report.

The science is shaping up to suggest that the damage done by an imminent overshoot of the 1.5-degree threshold may not be easily undone. Still, that looks like the world we are entering. So, how could we draw carbon out of the atmosphere by achieving the “negative emissions” that might bring temperatures back down and, in the best-case scenario, stabilize the climate system?

The most obvious action is to bolster and increase carbon sinks by planting trees or encouraging natural forest regrowth. In the past decade, the world has developed a modest carbon market, using forestry and other projects that soak up CO2 to earn carbon credits that can be sold to offset carbon emissions by industry and nations.

Proposed solutions like solar radiation would be like “turning on the air conditioning in response to a house fire,” a scientist says.

The market has been widely discredited by failed, poorly monitored, and fraudulent forest schemes. But, if better managed and audited, it could be repurposed as part of an effort to generate negative emissions.

One proposal favored by many climate scientists would have the trees harvested and burned in power stations, so new carbon-grabbing trees could be planted on the vacated land. If the power-plant CO2 emissions were then captured and kept out of the atmosphere, the result could be an energy system that drew CO2 out of the air.

But the scientific consensus is that there isn’t room on a crowded planet for enough forests. Currently, work to protect and restore forests is soaking up an estimated 2 billion tons of CO2 annually. But lowering global temperatures by an average of even 0.1 degrees C would require a total of a hundred times more, according to the IPCC. And recent studies suggest 400 billion tons might be required to get back to 1.5 C by 2100.

Another idea is to industrialize carbon capture through the mass deployment of chemical plants that use solvents to extract CO2 from the air and convert it to inert material. This remains, at least for now, prohibitively expensive, costing hundreds of dollars for every ton removed.

Many scientists regard such carbon-capturing solutions as fanciful. And, given that we may need them in a hurry after some major planetary emergency such as warding off a tipping point, they could not be deployed fast enough. If a quick fix were needed — even a temporary one to “peak shave” temperatures while negative emissions were fast-tracked — we would need some form of outright geoengineering.

Most likely, these scientists say, this would involve shading the Earth from solar radiation by injecting into the stratosphere sulphur aerosols similar to those sometimes released in volcanic eruptions. Spraying from fleets of aircraft would have to continue for as long as the cooling was required. But it might work, and it might do so quickly and cheaply enough to be a realistic proposition. Researchers are enthusiastic. The British government last year invested $80 million to explore the potential of solar modification, including small-scale real-world experiments.

But others are horrified. They warn that leaving atmospheric greenhouse-gas levels high will also leave the world’s weather systems fundamentally altered. Even if the shading can get us back to 1.5 C of warming, the weather will not revert.

It took until 2025 for U.N. negotiators to even acknowledge the need to address how to handle an overshoot.

“Having temperature targets makes solar engineering seem like a sensible approach because it may lower temperatures,” says Watson. “But it does this not by reducing but increasing our interference in the climate system.” The world’s weather would still be broken. He likens it to “turning on the air conditioning in response to a house fire.”

IPCC scientists have consistently argued that achieving the Paris target will ultimately require some form of negative emissions. But it took until the 2025 climate conference in Belem, Brazil, for U.N. negotiators to acknowledge the need to address how to handle an overshoot, declaring in its final statement that “both the extent and duration of an overshoot need to be limited,” though without going into further detail. So far, only Denmark has a national negative emissions target — promising reductions of 110 percent from 1990 levels by 2050.

Negative emissions are “not a political project yet,” says Oliver Geden of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. And even the suggestion seems optimistic right now, when even modest international efforts to achieve “net zero” emissions by mid-century are falling far short, and the world’s second largest emitter, the U.S., has exited the entire project.

But the warnings are stark. Without action to draw down atmospheric carbon, the climate system will likely move into an era of accelerated warming that may be impossible to halt. Overshoot will be permanent.