In early 2025, Sian traveled deep into the mountains of Shan State, on Myanmar’s eastern border with China, in search of work. He had heard from a friend that Chinese companies were recruiting at new rare-earth mining sites in territory administered by the United Wa State Army, Myanmar’s most powerful ethnic armed group, and that workers could earn upwards of $1,400 a month.

It was an opportunity too good to pass up in a country where the formal economy has collapsed since the 2021 military coup and nearly half of the population lives on less than $2 a day. So Sian set off by car for the town of Mong Pawk, then rode a motorbike for hours through the thick forest.

Hired for daily wages of approximately $21, he now digs boreholes and installs pipes. It is the first step in a process called in situ leaching, which involves injecting acidic solutions into mountainsides, then collecting the drained solution in plastic-lined pools where solids, like dysprosium and terbium, two of the world’s most sought-after heavy rare-earth metals, settle out. The resulting sediment sludge is then transported to furnaces and burned, producing dry rare earth oxides.

China processes most of the world’s rare earths, but a significant portion of the raw material is mined in Myanmar.

As geopolitics scrambles supply chains and global demand for rare earths has mushroomed, mining for these materials is on the rise in Myanmar, where thousands of laborers like Sian are flocking to mine sites on the country’s eastern border with China. But the extraction and processing of rare earths is taking an increasing toll on the mine workers, nearby communities, and the environment. “The toxic effects of rare-earth mining are devastating, with poisoned rivers, contaminated soil, sickness, and displacement,” said Jasnea Sarma, an ethnographer and political geographer at the University of Zurich.

China holds most of the world’s rare earth processing facilities, but since the early 2010s it has tightened restrictions on domestic extraction as its impacts have become apparent. Rare earth mining has since expanded just over China’s southwestern border in Myanmar, where labor is cheap and environmental regulations weak.

The industry is highly secretive. But this September, a journalist from Myanmar, who prefers not to be named for security reasons, visited rare earth mining sites in Wa territory near Mong Pawk for this article. This reporting confirmed that rare earth mining overseen by Chinese companies is rapidly expanding in Wa territory, and it provides firsthand details of the many ways this activity contaminates water sources and contributes to deforestation, damage to human health, and loss of livelihoods.

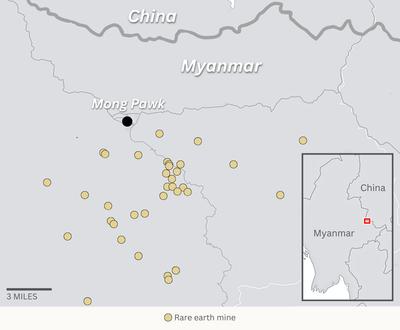

Rare earth mining sites in the Mong Pawk region. Source: Shan Human Rights Foundation, Stimson Center. Ella Beiser and Federico Acosta Rainis / Pulitzer Center • Created with Datawrapper • Copyright OpenStreetMap contributors

The 17 elements known as rare earths are distributed widely across the Earth’s crust, but they are extracted in relatively few places due to ecological, geopolitical, and economic constraints. Used in electric vehicles and wind turbines, rare earths are also needed for the production of military hardware and other advanced technologies.

Rare earths are designated as “critical minerals” by many of the world’s superpowers — vital to economies and national security but vulnerable to supply chain disruption. They are also a key commodity in the trade war between the United States and China, which has tightened rare earth export restrictions over the past year in response to escalating tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump.

China still processes most of the world’s rare earths, but its import data shows that a significant portion of the raw material is mined in Myanmar. This makes Myanmar one of the global rare earth mining boom’s largest sacrifice zones — defined by researchers and environmental justice advocates as places that disproportionately endure the harmful effects of extraction so that others may benefit.

“This borderland has seen one extractive wave after another: teak, opium, jade, and now these so-called green minerals,” says an expert.

No publicly accessible corporate databases show the licensing of active rare-earth mining operations in Myanmar. But Chinese customs data indicates that approximately two-thirds of its rare earth imports came from Myanmar between 2017 and 2024, according to research conducted by the Institute for Strategy and Policy-Myanmar, a think tank based in Thailand.

Satellite image analysis conducted by the nonprofit Myanmar Witness, in partnership with the Myanmar media outlet Mizzima, also reveals hundreds of rare earth mining sites on the country’s eastern border. The area is home to Indigenous communities who have been at odds with central military authorities since the country’s independence from Britain in 1948. For decades, the military has negotiated ceasefires with ethnic armies while allowing them to engage in a range of cross-border enterprises, sometimes while taking a cut of the profits.

“This borderland has seen one extractive wave after another: teak, opium, jade, amber, bananas, and now these so-called green minerals,” said Sarma. “Ethnic armies have to do business with China to survive. China needs the resources, and local communities, after decades of conflict, depend on this to live.”

As the rule of law deteriorated following Myanmar’s 2021 coup, the pillaging of its natural resources accelerated. In October 2024, an ethnic army fighting the military seized the rare-earth mining hub of Pangwa, in Kachin State, from a military-aligned warlord, and China, which arms and supports the Myanmar military, closed its gate into the town. More than a year later, rare earth mining in Kachin has yet to fully resume, while areas of Shan State — controlled by the United Wa State Army and another ethnic army with close ties to China — appear poised to emerge as new rare-earth mining frontiers.

“What began as discovery has moved into full extraction… pulled by proximity to China,” said Xu Peng, a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre for the Study of Illicit Economies, Violence, and Development at SOAS University of London.

Earlier this year, the Shan Human Rights Foundation, a local civil society organization, used satellite images to expose rare earth mining in Shan State for the first time. This research, alongside further satellite analysis conducted by the Stimson Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, revealed 63 rare earth mining sites near the Chinese border and two sites bordering Thailand. Some of these sites were established as early as 2015 and may no longer be operational, but most emerged after the coup.

Armed authorities in Shan State keep a tight lid on information, including the names of Chinese companies operating there.

The news of these Shan State mines sparked public outcry in Thailand, where chemicals associated with rare earth mining have heavily contaminated rivers relied upon for drinking water, agriculture, and fishing. But no such response has emerged in Shan State, where mining companies and armed authorities keep a tight lid on information, including the names of the Chinese companies operating there.

Businesses involved in Myanmar’s rare earth mining industry have reason to be secretive: Their operations put people and the environment at risk. “This year, there was an accident during excavation and a worker was buried,” said Sian. “Only later, after the soil was washed away by heavy rain and landslides, was his body recovered.” In 2023 and 2024, local media outlets documented the death or disappearance of dozens of workers in three landslides in Kachin State.

Research published in March by scholars at the University of Warwick and the Kachinland Research Centre, based in Kachin State, attributed these landslides to “large-scale deforestation,” undertaken to both clear land for mines and supply firewood for the furnaces used to convert sediment sludge to dry rare earth oxides — a process that can take 48 to 72 hours. Another factor contributing to landslides, the researchers found, was the injection of water and leaching agents into the hillsides.

Satellite views of a rare earth mine recently established near Mong Pawk. Copyright 2020-2025 CNES / Airbus DS / Earth Genome

Workers in Shan State described fragile landscapes. “The environment near the site faces constant problems like landslides, mountain collapses, and stream flooding, especially during the rainy season,” said an on-site cook, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Large trucks often fall into sinkholes. The ground is soft, which sometimes leads to fatal accidents.”

Chemical exposure and the inhalation of toxic particles are also major concerns. “Many workers suffer from lung issues,” said Sian. “Because of contact with acid, some workers also develop rashes, redness, itching, or chemical burns on their skin and eyes.”

Nearby communities also feel the impacts. “Many households reported more frequent respiratory illnesses, skin conditions, and headaches, which they believe are linked to pollution from nearby mining activities and dust from deforestation,” said the journalist who visited Wa for this article. “In some villages, families said children and elderly people are especially affected. They worry that contaminated water sources from mining operations are harming both their health and their livelihoods.”

Research conducted by Myanmar Resource Watch, a civil society organization, found that companies mining rare earths in Myanmar rely on a wide range of chemicals classified as hazardous — including sulfuric, nitric, and hydrochloric acids — and that these companies routinely violate regulations on the chemicals’ import, transport, storage, use, and disposal. Not only can hydrochloric acid kill aquatic life, it also dissolves heavy metals, like cadmium, lead, arsenic, and mercury, and radioactive materials, like thorium and uranium, from soil and rocks.

A chemical pool at a rare earth mining site near Mong Pawk, in territory controlled by the United Wa State Army.

While no quantitative studies have been published on the environmental impacts of rare earth mining in Shan State, research from Kachin State offers some indication of the potential risks. In April, Tanapon Phenrat of Thailand’s Naresuan University published a study based on analysis of surface water and topsoil samples taken at or downstream from rare earth mining sites in Kachin. He identified “severe contamination” of the water, “extremely acidic pH levels,” and “alarmingly high concentrations” of ammonia, chloride, radioactive elements, and toxic heavy metals.

He also found that metals and metalloids present in water samples posed “substantial risk” to aquatic ecosystems and that the water at some of the testing sites was “entirely unsuitable for human consumption, irrigation, or fish culture without extensive treatment.”

Rare earth elements themselves can also adversely impact human health, according to secondary research published in 2024 in the journal Toxics. This review found that exposure to rare earth elements through inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact can destroy organ structure and function, affecting the respiratory, nervous, cardiovascular, reproductive, and immune systems.

“Right now, the way these minerals are governed often overlooks a major problem,” said Thaw Htoo, a PhD candidate of geography and sustainability at the University of Lausanne who conducts her research using a pseudonym due to safety concerns. “They are essential for the global green transition, yet their extraction is happening with almost no rules. The case of Myanmar shows why we need to rethink what ‘critical minerals’ means and make sure we consider not only supply security, but also the safety and well-being of communities and the environment.”