When the wildfire reached Jon Cummings’ backyard last summer, it had already traversed 50 miles of rugged terrain in Idaho’s Salmon-Challis National Forest. Thick smoke dimmed daylight and embers sailed on hot currents. While firefighters were able to preserve Cummings’ house and property, his neighbors up the river were less fortunate. “No houses burned, but when those folks came home it was a total moonscape,” he said.

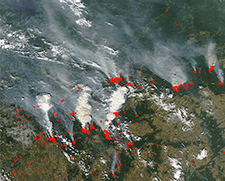

Wildfires last summer burned more than 9 million acres across the U.S., predominantly in the West and Southwest. Only two other times in the past 50 years have fires burned so extensively: first in 2006, then again in 2007. Twice more in the last decade fires fell just short of claiming this much acreage.

Increasingly, forestry experts say this ominous trend bears the fingerprints of climate change: As average air temperatures rise and water evaporates more rapidly from vegetation and soil, the parallel rise in precipitation needed to offset these changes has not kept pace. Most models predict the deficit will only worsen in years to come.

“The initial signs of climate change — they’re here,” says Amber Soja, a senior research scientist at NASA who studies the interaction of fire and climate. “We have evidence in our wildfires.”

In the Rocky Mountains, reduced snowpack in winter, earlier melting in spring, fewer inches of rainfall, and warmer autumns are all contributing to a fire season that has lengthened by nearly 80 days in the last three decades, researchers say. The duration of individual fires has also jumped, from an average of one week to five weeks.

Anthony Westerling, a fire specialist at the University of California, Merced, and an expert on fires in the U.S. West, notes that intensifying aridity in the Rocky Mountains as the region warms will exacerbate the problem. “There is going to be a huge percentage increase in burned area that we’ve only just begun to see,” he said.

Similar changes are emerging around the world, researchers note, most notably in the boreal forests that stretch across the northern latitudes from Alaska east through Siberia. In Canada, the average amount of land burned annually by wildfires has doubled since the 1970s, according to Mike Flannigan, a professor of wildland fire at the University of Alberta. “And we expect another doubling to quadrupling of fire over this next century,” said Flannigan. “We attribute this — and I’ll be quite clear — to human-caused climate change.”

‘There is going to be a huge percentage increase in burned area,’ says one scientist.

In Russia, where Soja focuses her research, the figures have also ratcheted up. A bad fire season now burns tens of millions of acres. Just last year, a record 74 million acres were consumed by wildfire, largely in the taiga of eastern and central Siberia. “It’s about time we change our definition of normal, because there is just so much burning in Russia,” she said.

But growth in the number of acres burned is not all that defines wildfire severity. Of equal concern is the depth to which many fires now reach, pushing farther underground into parched soils.

This is especially problematic in the boreal forests, which store more than 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial carbon, much of it bound in peat bogs — essentially carbon-rich mosses that have accreted, layer upon layer, over millennia. As these bogs dry out and become more flammable, wildfires bore farther down, releasing much more carbon than a conventional forest fire.

Flannigan pointed to a 2002 study of particularly severe peat fires in Indonesia in 1997 that released the carbon equivalent of an estimated 20 to 30 percent of that year’s global greenhouse gas emissions. “But the peat reserves in the boreal dwarf those of Indonesia,” he said. “If these go, emissions from the Indonesian fires would be a drop in the bucket.”

Boreal forests could be contributors to global warming rather than mitigating forces against it.

These changing conditions put northern forests at risk of being transformed from repositories, or sinks, of carbon, to overall sources of CO2. The forests would then be contributors to global warming rather than mitigating forces against it.

The shift from carbon sink to source has already been documented in British Columbia: A 2008 analysis published in Nature concluded that, since 2003, fires and unprecedented tree death from bark beetle infestations had turned almost 150,000 square miles of forest in the province — an area the size of Montana — into a source of carbon dioxide emissions. All of Canada’s vast forestland now sits precariously on this fulcrum, and may soon emit more carbon than it sequesters, according to the Canadian Forest Service.

“As wildfires continue to increase, we expect to see our [Canadian] forests become a carbon source,” said Flannigan.

While forest regeneration would normally help to counterbalance these emissions, ecosystem shifts under the pressure of climate change are now casting uncertainty on this cycle. In a process called “green desertification,” for instance, grassland steppe across Russia is replacing taiga in the aftermath of severe fires; the standard mix of conifers and hardwoods that constitute the taiga show no signs of returning. “It’s likely that the entire 21st century will be dominated by these transition effects,” says Westerling, who has observed similar changes in the western U.S. “Places where these fire disturbances are increasing dramatically are going to look very different in the near future.”

The health effects of severe wildfires also present a growing concern, particularly as populations expand along forest fringes. Insurance giant Munich Re estimated that particulate matter and “toxic smoke” from Russia’s 2010 wildfires, combined with record temperatures, accounted for an additional 56,000 deaths in July and August of that year, most of these in Moscow. And last year a program manager with the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare declared an air quality “crisis” in the small town of Salmon, near Jon Cummings’ property.

This year, like last, the U.S. Forest Service forecasts persistent drought and elevated fire risks across the western and southern U.S. “We anticipate 2013 to be another challenging year to manage fire,” said Tom Tidwell, chief of the Forest Service, in a February 20 memo.

For most of the 20th century, the U.S. Forest Service pursued an aggressive agenda of fire suppression that allowed forest understory — which in earlier eras had been routinely thinned out by fires — to grow thick and fuel more intense blazes. “Forest ecosystems have evolved with fire,” explains Keith Konen, a silviculturist for the Forest Service in Montana. “Through 100-plus years of fire suppression this natural process has been altered.”

In 1995, the Forest Service established a new fire policy, which recognized that “wildland fire, as a critical natural process, must be reintroduced into the ecosystem.” Since then, in an effort to remove understory growth, the Forest Service has allowed fires in some federal forests to burn out on their own. Today, however, climate change has further complicated the Forest Service’s job: The agency must oversee the continued use of fuel-culling fires at a time when a warming climate makes controlling these fires riskier, says Scott Stephens, a professor of fire sciences at the University of California, Berkeley.

Currently, 65 million acres of Forest Service land — or one-third of the agency’s total holdings — remain at high or very high risk of catastrophic wildfires due to the buildup of fuel. Only a small fraction of this buildup is managed or removed through timber harvesting and fire in a given year.

A third of U.S. Forest Service land remains at high risk of catastrophic wildfires.

Under a new planning rule introduced last year, the Forest Service is drawing up management plans for individual national forests that incorporate new science on climate change and fire suppression. Stephens said Forest Service officials are increasingly shying away from mechanical thinning of forests and prescribed burns, in favor of allowing naturally occurring fires to burn in a controlled manner to eliminate thick understory.

“Fire management is being funded now to emphasize the resource benefits of lightning fires,” said Stephens. He expressed guarded optimism that the Forest Service’s new policies will help reduce the severity of fires in the American West. “I think [they] have the potential to get things done at scales that make a difference and reduce the trend of large fires,” he said.

But other researchers are skeptical. A 2009 study of the boreal forest published in Global Change Biology and coauthored by Flannigan reflects the prevailing sentiment: “There may be only a decade or two before increased fire activity means fire management agencies cannot maintain their current levels of effectiveness,” write the authors.

Intensifying wildfires, coupled with austerity budgets that have reduced firefighting capabilities, are a global problem. Soja, the NASA fire expert, said that budget cuts in Russia have led to reduced firefighting capabilities since the early nineties. “It’s just not possible for Russia, for the Canadians, to manage these large fires,” Soja said.

Westerling says that the same may be true of the U.S. “We just have nothing like the resources you would need to treat these areas on an ongoing basis,” he said, referring to the logging, thinning of understory, or controlled burns that can lessen the intensity of forest fires. The Forest Service’s fire prevention and suppression funds have been slashed by more than $500 million, or about 15 percent, since 2010.

“Fires are simply going to be reintroduced by nature, augmented by climate change,” he said. “I think the land’s going to burn, and then we’ll go from there.”