The chaotic events unfolding at the damaged Fukushima-Daiichi reactors along Japan’s northeast coast have inspired intense new scrutiny of the country’s nuclear policies. While Japan excels in some anti-pollution measures, the lack of a vigorously independent press and a strong judiciary has enabled Japanese industry to resist legislation to safeguard the environment and human health. The nuclear power industry, a powerful player in Japan’s politically dominant construction industry, has pressed ahead with its plans — endorsed in 2006 by the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry’s “New National Energy Policy” — to mold the country into a “nuclear state.” In addition to 54 existing nuclear power plants that until last week supplied 30 percent of the country’s electricity, a dozen new nuclear plants are planned or under construction.

One in particular has exposed a deep public divide. The proposed Kaminoseki nuclear plant is to be built on landfill in a national park in the country’s well-known Inland Sea, hailed as Japan’s Galapagos. For three decades, local residents, fishermen, and environmental activists have opposed the plant, saying it should not be built in the picturesque sea, with its rich marine life and fishing culture dating back millennia. The Inland Sea has also been the site of intense seismic activity, including the epicenter of the 1995 Kobe earthquake that killed 6,400 people.

But in a sign of the immense clout of the nuclear power industry, a utility has barreled ahead with plans to build the Kaminoseki plant, despite what may be the most intense opposition yet to a Japanese nuclear project. In 2009, the utility began clearing forests for the project — located just 50 miles from Hiroshima — and reclaiming land from the sea. Nothing, not even intensifying protests, seemed able to stop the plant’s construction — until, that is, last week’s earthquake and tsunami set off the crisis at the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant. Now, for the time being at least, work has halted on the Kaminoseki project.

“We have to stop it,” Masae Yuasa, a professor of International Studies at Hiroshima City University and a leading opponent of the plant, told me when I visited Japan last fall. In words that have a chilling resonance now, she continued, “Once an accident happens, there is no border. I want to be more polite, but we have to stop it. I am a person from Hiroshima. I cannot be quiet about it.”

Formed by Honshu to the north and Shikoku and Kyushu islands to the south, the shallow, placid Inland Sea stretches for 300 miles, dotted with over 3,000 tiny islands. Donald Richie, author of the classic 1971 travel book, The Inland Sea, thought it one of the country’s most breathtaking sights, describing “one island behind the other, each soft shape melting into the next until the last dim outline is lost in the distance.” Dismayed by rapid post-war industrialization, Richie expressed prescient fears that the sea faced serious threats from development, and in the decades since, land reclamation, sand dredging, and pollutants from heavy industry on Honshu’s coast have taken a toll. But the sea — also known as Seto Inland Sea — remains one of Japan’s most inviting tourist attractions, drawing kayakers and bikers to the fishing villages and shrines along its shores.

The entire sea was declared a National Park in 1934, home to rare or endemic seabirds, fish, mollusks, and a population of the endangered and nationally protected finless porpoise. But park designation in Japan is more a notional category than a guarantee of protection: Because the island nation has always been land-poor and densely populated, the park system contains public and private property, liberally allowing all manner of activities, including agriculture, logging, and industry.

Once hailed for enabling the post-war renaissance, the construction industry has become a juggernaut.

Indeed, those laissez-faire park policies have come to reflect entrenched political and cultural priorities. Once hailed for enabling the post-war renaissance, construction — including construction of nuclear powerplants — has become a juggernaut. Astonishingly, tiny Japan, smaller than California, recently boasted the largest construction industry in the world. (It now rates third, behind China and the U.S.) To maintain its hegemony, its lobby has run advertising campaigns identifying nature as “the enemy,” tapping into fears of earthquakes, tsunamis, and typhoons. It has evaded oversight and opposed legislation governing toxic dumping. Japan had no comprehensive policy regarding environmental impact statements until the late 1990s.

The cost to the environment has been incalculable. As government agencies compete to pad budgets and snag prestigious jobs, bridges and roads-to-nowhere have proliferated. Much of the coastline has become littered with concrete barriers to foil erosion and virtually all the country’s rivers have been dammed and lined with concrete, a process one writer terms “state-sponsored vandalism.” Japanese artists and filmmakers have expressed increasing dismay, but organized environmental opposition has never gained the widespread support that it has in the West.

But in 1982, when the Chugoku Electric Power Company identified the island of Nagashima as the site for the Kaminoseki nuclear power plant, the plans met stiff resistance from residents, fishermen, scientists, and a small cadre of nuclear activists in nearby Hiroshima. Home to the town of Kaminoseki, population 3,700, Nagashima lies at the southeast end of the Inland Sea, within the designated park boundaries. According to the plans, two reactors would be built, with only one sited on Nagashima itself. The other was to be built on “reclaimed land,” with landfill making up 40 percent of the plant site. Water to cool the reactors would be drawn from north of the island, effluent released to the south.

Click to enlarge

While there were divisions among residents of Kaminoseki — some felt that they had little choice economically but to accept the plant — natives of Iwaishima, an island two miles away where people have harvested seaweed and fished for octopus and sea bream for more than a thousand years, were united in opposition. Their age-old settlement faces the coastline where the reactors will be built, and their voices carried weight: They have been celebrating their way of life in a festival held regularly since 886. Some 90 percent of Iwaishima’s 522 residents opposed the plant from the beginning, refusing buyouts from Chugoku and staging weekly protests on the beach for the past 27 years, declaring, “We will not sell our sea for a nuclear power plant.”

Chugoku pressed ahead regardless. In 1999, to comply with new Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry regulations, the company completed an environmental impact assessment. Opponents denounced it as “grossly inadequate,” pointing out that it glossed over threats to populations of protected species, including the finless porpoise. Members of Japanese scientific societies weighed in. The Ecological Society of Japan, the Japanese Association of Benthology, and the Ornithological Society of Japan have repeatedly criticized the assessment, issuing detailed resolutions calling for significant revisions. Opponents expressed concerns about the destruction of organisms sucked into water filters, about disturbance of breeding populations of seabirds, about the rise in water temperatures caused by effluent. Critics pointed out that it takes up to two years for replacement of the Inland Sea’s water; slightly warmer discharge from the plant could potentially raise temperatures and curtail breeding among fish and shellfish. Chlorine used to kill barnacles could alter the sea’s chemical composition. In February 2010, the three societies issued a joint statement calling for “suspension of construction… and a demand for reinvestigation followed by measures to conserve [the area’s] biodiversity.”

Chugoku went ahead with its seismological surveys, and in 2008, the governor of Yamaguchi Prefecture issued a permit allowing the company to begin land reclamation, despite the fact that it did not possess a spotless reputation in nuclear safety. Last year, the government’s Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency began issuing ratings of the country’s commercial reactors on a five-point scale. Chugoku operates many hydroelectric plants but only one nuclear facility: two reactors in Shimane Prefecture, on the west coast of Honshu. Shimane earned the lowest possible grade, and the agency found 511 inspection failures at the site. It chided the company for causing “greatly ruined trust in nuclear power generation.”

Opposition to nuclear power has long existed in Japan, where fears are sometimes dismissed as ‘Hiroshima Syndrome.’

In 2009, Chugoku began clearing forests on Nagashima and attempted to start reclaiming land offshore. Progress was repeatedly blocked by protesters. In October of last year, Japan hosted the biennial meeting of the UN’s Convention on Biological Diversity, held in Nagoya. Feeling that an appeal to the international community was their last hope, a coalition of protest groups submitted a petition with 860,000 signatures to the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and held a press conference at the meeting, taking out a prominent ad in the Asian edition of the International Herald-Tribune that expressed concerns about the potential for earthquakes causing “contamination” and “radiation release.”

The protests became more desperate, again stalling work. Videos online show protestors linking arms on beaches, security forces shoving against them. Thirty fishing boats joined the protest, and kayakers fouled lines anchoring a crane ship at the site. In January, five young men parked themselves outside government offices in Yamaguchi City, launching a ten-day sit-in and hunger-strike. But after obtaining a court order outlawing interference, Chugoku resumed landfill operations on February 25, announcing its intention to begin plant construction in June 2012 and power production in 2018.

Opposition to nuclear power has long existed in Japan, where fears are sometimes dismissed as “Hiroshima syndrome.” A 2005 International Atomic Energy Agency survey revealed that only one in five people in Japan considered nuclear power safe enough to justify new plant construction. In 2008, members of hundreds of opposition groups paraded through central Tokyo to protest the building of the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant, designed to allow commercial reprocessing of reactor waste to produce plutonium. Located at the northeast tip of Honshu, Rokkasho was forced, like the reactors at Fukushima, to rely on emergency generators after the recent quake, although Rokkasho’s generators were not disabled by the tsunami.

Referendums have stopped plans for some nuclear plants in Japan, but Masae Yuasa, founder of a group opposing the Kaminoseki plant, said she cannot think of a single instance of a nuclear plant being stopped by public protests alone. Until now, Japan has been a country where Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, warnings by the International Atomic Energy Agency, and its own alarming history of nuclear incidents — some causing fatalities — have had little effect on policy. Gavan McCormack, an Australian historian, has described the government as “nuclear-obsessed.” Other than China, Japan is currently planning more nuclear plants than any other country, and it is pursuing the full nuclear cycle, including the operation of fast-breeder reactors to produce plutonium, one of which, Monju, had to be shut down for 15 years — from 1995 to 2010 — after a major sodium coolant leak.

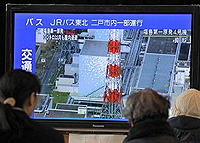

But on March 11, when a 9.0 magnitude earthquake struck off Japan’s northeast coast, triggering the tsunami that killed thousands and cut power to the Fukushima reactors, leading to explosions, fires, and radiation releases, Japan found itself facing the most horrific consequences of its headlong rush to be a “nuclear state.” No one can predict how these events may change the country’s nuclear policy. But on March 13, the governor of Yamaguchi Prefecture — the same man who issued the permit to Chugoku Electric to proceed with landfill operations — officially asked the company to stop. Two days later, Chugoku announced a “temporary” halt. In an email, Yuasa expressed her belief that events would force the government to change.

“Words,” she wrote, “cannot conceal the facts.”

Correction, March 18, 2011: An earlier version of this story quoted Masae Yuasa, founder of a group opposing the Kaminoseki plant, as saying that she could not think of an instance in which a nuclear power plant was stopped by public opposition in Japan. In fact, referendums have stopped plans for some nuclear plants in Japan. Masae said that public protests alone, in the absence of referendums, have not stopped a nuclear power plant from being built in the country.