Along the Elwha River on Washington state’s Olympic Peninsula, the largest dam removal project in the world is nearing completion. The scale of the undertaking is on display as a National Park Service employee unlocks a fence guarding a colossal construction crane looming over what is left of the Glines Canyon Dam, which once rose 210 feet above the river. A narrow, vertiginous walkway, which will eventually serve as a visitors’ viewpoint, ends in mid-air above a yawning 150-foot-wide chasm cut in the concrete. Below, the unleashed river roars across what’s left of the structure. Upstream, the view is dominated by a vast bowl of sediment, the bottom of former Lake Mills.

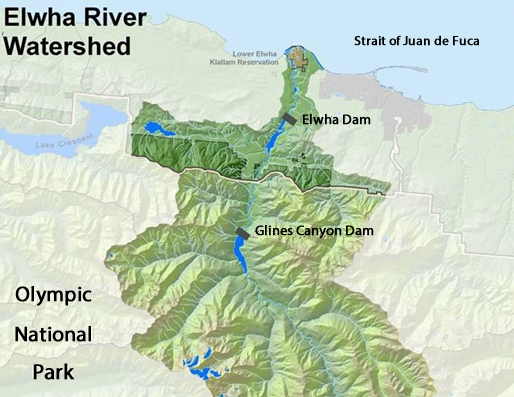

The remains of the Glines Canyon Dam are located 13 river miles from the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the passage from the Pacific Ocean to Puget Sound. Eight miles downstream, the Elwha dam — built a century ago without accommodation for fish passage and long reviled by Native Americans and fishermen — is already gone, demolished in 2011 and 2012.

With the river now flowing freely, the legendary salmon runs — blocked for a century — have begun a tentative return to the Elwha’s 70 miles of salmon habitat, much of it in Olympic National Park. It is the dream of restorationists to bring back these extraordinary fish to the Elwha, most of which remains pristine, shaded by the gargantuan old-growth firs and cedars and primeval ferns for which the Olympic Mountains are famous.

The demolition of the dams is an evolving experiment that entails the restoration of an entire watershed.

The demolition of these two dams has become an evolving scientific experiment, one that entails the restoration of an entire watershed, from salmon to alders to otters. The two dams had starved the lower reaches of the watershed of sediment, and the lakes that formed behind them were filled with unnaturally warm water. Lake Mills and Lake Aldwell also elevated water temperatures downstream, and marine nutrients failed to cycle into the ecosystem, affecting species throughout the food chain, from black bear, eagles, and osprey at the top, to frogs and flies.

The dams caused the near-extinction of native strains of samon including chinook, pink, and chum. Given their position at the center of this ecosystem, even a modest return of these migratory fish is crucial to restoring the Elwha watershed. The other major challenge facing the National Park Service is the management of tens of millions of cubic yards of sediment that have built up behind the dams.

Politically, what is happening on the Elwha may alter the landscape for large-scale dam removals in the United States as debates continue over the Pacific Northwest’s heavily-dammed Columbia River basin and Oregon’s Klamath. By 2020, 70 percent of the 84,000 dams in the U.S. will be more than 50 years old; many will require repair, removal, or replacement. Roughly 4,400 are at risk of failure, and the Association of State Dam Safety Officials estimates it will cost $21 billion to repair them. In the past two decades alone, more than 500 dams in the U.S. — most of them small — have been demolished.

Already, visible changes along the Elwha are ‘jaw dropping,’ says one scientist.

The Elwha is among the most ambitious ecological restoration projects in U.S. history, second only to efforts to re-engineer water flows in the Florida Everglades. Already, visible changes along the Elwha are “jaw dropping,” says Anne Shaffer, director of the Coastal Watershed Institute. A couple of thousand salmon have spawned in the river, and trees and grasses are recolonizing new terraces formed by the drawdown of Lake Mills and Lake Aldwell.

“This is the first time a system is being put back together,” says Ian Miller, coastal hazards specialist for Washington Sea Grant, a research and conservation organization.

Federal scientists knew that dealing with vast amounts of sediment built up behind the two dams would be their greatest challenge, but even they underestimated the scope of the problem. Demolitian experts made short work of the Elwha Dam. Glines Canyon, built in 1927, has been a slower, staged process as workers whittle notches, a few feet at a time, to control the release of a vast delta of clay, silt, sand, gravel, and cobblestones.

That sediment release far exceeds any in history. In 2010, hydrologists predicted that 24 million cubic yards had been trapped behind the dams. Last year, the estimate jumped to 34 million, enough to fill a football field five miles high. As sediment increased, so did the Elwha project’s costs, from $182 million in 2004 to more than $325 million today. About half of the sediments may remain in place, but the last 50 feet of Glines Canyon Dam has been holding back the biggest slug of all, 28 million cubic yards.

Demolition, regularly halted during “salmon windows” to give fish a chance to spawn without being smothered by sediment, has also been delayed. Last year, in a development that alarmed residents of Port Angeles, sediment began clogging the new $163 million water quality facilities built in town, which take drinking water from the river’s surface and a nearby well. Those facilities are the largest line item in the Elwha restoration budget, and removal was on hold for a year as a Park Service contractor completed $3.8 million in repairs. Work resumed this month, to be finished next year.

As planned, sediment is meant to move downriver in pulses as notches are removed. “We’re trying to make the river do the work,” says Tom Hepler, a U.S. Bureau of Reclamation expert on the Elwha removals. The Elwha has obliged, thrilling biologists by filling in pools and forming new gravel bars.

Before the dams were built, the Elwha was home to all five species of Pacific salmon.

That’s essential to spawning salmon who need cold water flowing through their redds, the hollows where they lay their eggs, moderating temperatures and providing oxygen.

Along the Elwha, 700 acres of forest are being recreated, drawing from 400 native species, everything from Douglas fir to grasses and groundcovers, such as Oregon grape. By next year, crews will have planted more than 100,000 of 400,000 seedlings. In one stretch above former Lake Mills, new growth coats the sides with green fuzz, but the lake bed still has the raw look of a mining pit. Joshua Chenoweth, who heads the Elwha replanting, has been pleased so far. But he’s cautious about long-term prospects for plants in the drying, nutrient-poor sediment, noting, “It is a bit early to say.”

The Elwha is also the world’s largest salmon restoration project, but one influenced by political as well as scientific considerations. State and federal agencies are juggling the long-frustrated hopes and high expectations of diverse parties. Among them are the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, which has legal rights to Elwha salmon and whose reservation lies at the river’s mouth; sport fishermen; the city of Port Angeles; and the paper mill once served by the dams.

Before the dams were built, the Elwha was one of the Northwest’s great natural resources, hosting steelhead and all five species of Pacific salmon: sockeye, coho, chum, pink, and the legendary Elwha chinook, which commonly reached 100 pounds. Ten salmon runs — each genetically adapted to a specific seasonal migration — meant that the Elwha was full of migrating fish year-round, some 400,000 annually.

But the Elwha dam put a stop to that. Despite official warnings, the builder violated an 1890 law requiring fish ladders on dams, substituting a hatchery instead. Other dam builders followed suit, blocking salmon runs throughout the Northwest. That end-run determined state policies for decades, giving rise to a hatchery-dependent fishery during the hydroelectric boom of the 1920s to 1960s. For years, fish appeared in declining numbers at the base of the Elwha dam. By the 1990s, native sockeye were extinct, spring chinook and chum nearly so. Pink salmon were endangered, and summer steelhead scarce.

These declines, along with a 1910 prohibition against fishing, deprived the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe of a key food source and cultural touchstone. After their fishing rights were restored in the 1970s, the tribe objected to licensing the dams, citing their impact on the salmon fishery and a poor safety report predicting the Elwha dam might fail during high flood conditions. Built before federal regulation, it had never been licensed; Glines Canyon was overdue for relicensing. By this point, the dams served a single Port Angeles pulp mill.

The tribe’s fight for dam removal was joined by conservation groups, and in 1992, after a bruising political battle, Congress passed the Elwha restoration act. It empowered the Interior Department to buy the dams for $29.5 million and — if restoration of endangered salmon required it — tear them out.

Standing on a bridge just below Glines Canyon this summer, park visitors leaned out, calling excitedly when they saw salmon wavering through the water for the first time in a century. Conservationists and fishermen, however, have reacted with dismay to the federal fish restoration plan.

In 2008, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) team released a plan designed to help Elwha salmon survive the sediment and recolonize the river over 20 to 30 years, a time-frame acceptable to the tribe. To meet the schedule, the plan relied primarily on hatcheries, calling for a new $16 million hatchery to be built for the tribe near the river’s mouth, while the tribe agreed to a five-year moratorium on Elwha fishing.

The Elwha will be ‘the gold standard against which any other salmon restoration will be measured,’ says one expert.

Hatchery fish, however, have become increasingly controversial as they dominate fisheries. They are tied to diseases affecting wild populations, and studies show that wild fish possess greater fitness and superior genetic traits. In 2012, conservation groups sued the tribe and federal agencies, asserting that the plan’s reliance on hatcheries threatened wild fish and violated the Endangered Species Act.

As the dispute works its way through the courts, tribal and NOAA biologists continue to capture and tag fish that reach the tribe’s hatchery and Washington state’s rearing channel nearby, transporting them from sediment-laden lower channels to unspoiled habitat above the former Elwha dam. Last year, 600 adult coho were released in clear tributaries; half of them spawned. In 2012, 2,200 chinook, including 500 wild fish, fought their way up the Elwha. This year numbers appear similar.

Meanwhile, dramatic changes are taking place at the river’s mouth. Sediment, sand, and woody debris have begun restoring the beach east of the mouth, once reduced to a narrow strip of cobblestones. This may correct severe coastal erosion, according to scientists who are using “smart rocks” — radio-tagged pebbles — to track their transport down the river. The hope is that once-rich shellfish beds may return.

“The Elwha is a very important system to watch,” says Gordon Grant, a hydrologist at the Pacific Northwest Research Station in Corvallis, Oregon. “It tells us what to expect from a massive societal investment in river restoration.” He predicts that the Elwha, so much of it pristine, “will be the gold standard against which any other salmon restoration will be measured.”