In 2000, Gregory Stone, an oceanographer at the New England Aquarium, went diving in the Phoenix Islands, an uninhabited archipelago belonging to Kiribati in the remote central Pacific. The multi-colored reefs swarmed with sharks and other large predators, an abundance shared by perhaps only a handful of remote atolls around the equator.

“We were completely blown away,” Stone recalled. “It was the first time I had seen what the ocean may have looked like thousands of years ago.”

The following year, he suggested to the Kiribati government that it turn the islands into a marine reserve, and in 2008 the Phoenix Islands Protected Area (PIPA) was born. Encompassing an area the size of California, PIPA — which contains eight nearly pristine atolls — was the biggest marine reserve in the world at the time and harbored one of the planet’s richest assemblages of marine life. It was also being intensively fished for tuna.

Yet fishing was banned in only 3 percent of the reserve, mainly in the waters around the islands. In the rest of the reserve, the catch legal by international fleets actually rose in the following six years, reaching 50,000 tons annually, even as scientists warned fishing companies to reduce their take or face depleted stocks in a decade or two. But closing the rest of PIPA to fishing, President Anote Tong said in an interview in 2013, was for the indefinite future.

Late last year, however, Tong reversed himself and announced that all commercial fishing in the PIPA reserve would be banned as of January 1, 2015. Initial results from satellite tracking of fishing boats indicate that they are indeed staying out of the vast marine reserve. Observers are now optimistic that Kiribati will be able to safeguard the world’s richest marine protected area, thanks largely to cutting-edge satellite monitoring of foreign fishing fleets.

The checkered history of establishing a genuine marine reserve in Kiribati centers on Tong, who made a name for himself internationally as the spokesman for low-lying island nations threatened by sea-level rise, even as scientists were saying he was exaggerating those threats. He anchored his moral authority to ask for money to help his people migrate to higher land with claims that Kiribati had selflessly ended all fishing in PIPA in 2008. In Australia, an international committee has even promoted his candidacy for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The question Kiribati faces is how a tiny country is going to enforce a restriction on foreign fishing fleets.

By 2013, the contrast between claims and reality led to exposes in the press and calls from Greenpeace and UNESCO — which made PIPA a World Heritage Site on the understanding that fishing would be phased out — that Tong needed to make good on his promises or at least significantly reduce the catch inside PIPA. Then, last year Radio Kiribati announced that Tong and the cabinet had decided to close PIPA to all fishing at the end of 2014. “I was thrilled to see the turnaround,” recalls Bill Raynor, director of The Nature Conservancy’s Indo-Pacific division. “I hope other Pacific countries follow.”

What led Tong to change his mind has been the object of speculation among conservationists hoping to get other leaders to do likewise. Tetabo Nakara, an opposition member of parliament and former environment minister who oversaw the establishment of the reserve, says he believes Tong finally closed it to burnish his image as his third and last term ends this year. In any case, Tong’s exit will put enforcement responsibility on the next administration. Nakara says that if his party returns to power, it “will definitely enforce the closure.”

The question Kiribati now faces is how a country of 103,000 people with a tiny budget is going to enforce a restriction on the foreign fishing fleets that provide between a third and half of its revenue. Kiribati has only one patrol boat, which is based in Tarawa, 1,000 miles from the reserve.

Kiribati will have help in its drive to enforce the ban. The Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC) mandates that all fishing vessels must constantly transmit their positions with Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) satellite transponders, which are tracked by the countries in whose waters they fish. If the fishing boats don’t use the transponders, the vessel owners risk fines and losing their right to participate in the lucrative fishery.

Nonprofit groups are helping Kiribati by harnessing new satellite technology to spot illegal fishing.

“If they turn off VMS, it’s noticed,” says Martin Gotje of Greenpeace in New Zealand, who for years has been studying satellite data that tracks fishing boats. A $5 million grant by the Waitt Foundation will be used to buy a second patrol boat to be based in the Phoenix Islands.

More than half of the total Pacific skipjack tuna catch is hauled in by some 300 large purse-seine vessels, which lay nets around schools of the tuna that are then frozen and canned onshore. Nearly all the vessels have observers on board. “I would expect the purse-seiners will comply,” says Gotje.

Purse-seiners also have grown increasingly reliant on fish-aggregating devices, floating platforms that attract up to hundreds of tons of tuna and other fish for reasons that are still poorly understood. Equipped with sonar and transmitters that keep their owners apprised of the quantity of fish below, they could drift though PIPA gathering fish and be harvested as soon as they cross its border, creating a loophole in the no-fishing rule.

But since January 1, new regulations oblige most purse-seiners to place a VMS transmitter on each of their fish-aggregating devices. This should allow Kiribati to ensure that they are not used to draw fish out of PIPA.

The rest of the skipjack tuna catch is mostly hauled in by smaller long-line vessels that catch adult tuna, billfish, and sharks with lines up to 50 miles long from which dangle thousands of baited hooks.

At a meeting of the WCPFC late last year in Samoa, representatives of Pacific nations complained that long-line vessels do not accurately report their catch and sometimes fish inside their waters without licenses.

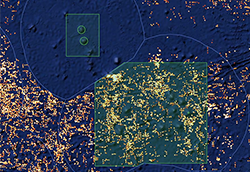

Kiribati will also get help in detecting these vessels from two non-profit groups that are harnessing new satellite technology to spot illegal fishing in remote areas. The Global Fishing Watch — a partnership of Google, Oceana, and SkyTruth — uses algorithms that detect fishing activity by monitoring a collision-avoidance radio signal called AIS used by many boats. (Fishing boats are not required to use AIS technology). A separate, more ambitious system unveiled this month by the Pew Charitable Trusts called Eyes on the Seas adds satellite radar telemetry and a data bank on fishing boats. “It’s time to follow the strategy of the spider and the fly,” says Josh Reichert, managing director of the Pew Environment Group. “The days of chasing poachers on boats are over.”

Closing PIPA is the single most effective act of marine conservation in history,’ says one scientist.

So far, both Greenpeace and Skytruth report that AIS data monitored from satellites show that the vessels that were fishing legally inside PIPA in December have not turned off their transponders — several can now be seen fishing outside PIPA. “Overall, I think most long-liners will comply as well,” says Gotje.

Scientists are divided on how useful the fisheries closure inside PIPA will be. John Hampton, manager of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community’s Oceanic Fisheries Program, says the closure will have minimal impact on the Pacific stocks of fish because the catch inside PIPA is made up largely of blue-water species that travel long distances. Most will simply be caught elsewhere and the total Pacific catch won’t significantly decrease, Hampton says. What’s needed to save species like the bigeye tuna — a mainstay for sushi whose population has been overfished down to just 16 percent of its original size — is to reduce the the catch, not displace it from one area to another, he says.

Daniel Pauly, a prominent fisheries scientist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, agrees but says the bigeye will benefit in other ways, as will the birds, dolphins, turtles, and other fish that are killed incidentally. “PIPA is pretty big and has islands and seamounts, so I’m confident that in each species there are going to be some individuals that will spend their whole life inside it,” he explains.

ALSO FROM YALE e360Fostering Community Strategies For Saving the World’s Oceans

Thus the density of marine life inside PIPA will rise back toward its natural level and boost genetic diversity, which will be increasingly valuable as marine life adapts to an ocean that is steadily becoming warmer and more acidic. Longevity also will increase, Pauly says, as older females in many species tend to produce more eggs.

How long it will take for these varied populations to rebound will depend on the species. For instance, oceanic whitetip sharks, which are now less than 7 percent of their virgin biomass, and silky sharks (less than 34 percent) reproduce much more slowly than skipjack tuna, which spawn year-round.

“Closing PIPA is the single most effective act of marine conservation in history,” Pauly says. “The fishing fleets are going deeper and farther and fishing out places that used to serve as refuges for a lot of species, so now there’s an urgent need to replace them with big, man-made protected areas like this one.”

Correction, January 30, 2015: A caption in slide 3 of the photo gallery for this article incorrectly stated that the group SkyTruth was working with Kiribati to monitor fishing activity in the PIPA reserve. SkyTruth is not working with Kiribati but is independently monitoring fishing activity in the reserve.