Atoll islands will have a better chance of staying above water in the coming decades if their ecosystems are healthy.

Atoll islands are made from sediment produced by corals, clams, snails, and types of algae that secrete calcium carbonate. If conditions are right, fragments of coral skeletons, shells, and other sediments made by marine life are piled up by waves, forming islands large and small. Although atoll islands make up just 0.02 percent of the island area across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, they are home to a diversity of human cultures and are important refuges for a quarter of the world’s tropical seabirds, multitudes of nesting sea turtles, and tropical plants.

Atoll islands and the wildlife they support face mounting challenges as the rate of sea level rise increases — it more than doubled between 1993 and 2023 — and because sea level will rise more this century than it did in the last. By 2100, sea level is projected to rise 11 to 40 inches, depending on the extent of actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Atolls that have lost some ability to generate sediment, such as those with degraded coral reefs, face an additional challenge. “They lose the capacity to keep up with sea level rise,” says University of Auckland ecologist Sebastian Steibl. In a 2024 study, Steibl and his coauthors contend that atoll islands will have a better chance of staying above water in the coming decades if ecosystems on the islands and in the surrounding waters are healthy. “For an atoll, we need to restore it to survive sea level rise,” he says.

Virginie Duvat, a coastal geographer at La Rochelle University, in France, who was not involved with the study, agrees that healthy ecosystems can increase the resilience of atoll islands. But she cautions that because coral reefs are the main source of sediment for islands, greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced to slow climate change so that reefs can keep growing. Coral reefs also face other threats, such as overfishing and declines in water quality, which tend to be most problematic near populated islands.

Along with global action to limit climate change and protect reefs, restoring islands’ terrestrial ecosystems can also help preserve them because of the indirect effect that nesting seabirds have on reef growth, scientists say. Seabird guano washes off islands and into reefs, where its nutrients boost coral growth and fish populations. Guano-fed reefs grow faster, producing more sediment, some of which is added to the islands. Unfortunately, many islands now have little habitat for nesting seabirds because their native broadleaf forests have been destroyed. Without seabirds, the production of reef sediments around atoll islands slows. In some places, however, scientists are working to reverse this trend.

Asked to draw a picture of a tropical island, many people would include a coconut tree. But coconut palms only came to dominate atoll islands in the 18th and 19th centuries, when European colonists established plantations to produce coconut oil for export. Most of the plantations were abandoned decades ago, but the trees persist.

With rats gone, wildlife on one island is starting to change. “We’re getting birds nesting in places where they hadn’t before.”

Today, coconut trees make up more than half of forests on Pacific atoll islands. Seabirds that evolved to nest in the bends and forks of tree branches find few places to nest in a palm tree’s lone vertical trunk, and birds that nest on the ground often can’t find space that’s clear of palm fronds and coconuts. In addition, seabirds avoid islands with rats, which eat eggs and chicks. Rats arrived centuries ago aboard ships and have spread to 80 percent of the world’s island archipelagos.

Reclaiming seabird habitat can help reefs persist and improve the resilience of atoll islands, according to Ruth Dunn, a seabird ecologist at Lancaster University, in England, who led a study to model the effects of rat eradication and forest restoration on both seabird populations and coral reefs surrounding islands in the Chagos Archipelago, a remote group of more than 50 islands in the center of the Indian Ocean. Because of a profusion of coconut palms and rats, about half of the islands have few or no seabirds, yet restoration efforts are underway to bring the birds back. According to Dunn’s model, if most native vegetation is restored and rats are eliminated, the islands could become home to more than 280,000 additional breeding pairs of seabirds, which would produce as much as 170 tons of seabird-derived nitrogen per year — enough to boost coral growth rates by more than 25 percent, on average. Dunn and her collaborators are currently exploring whether this increase is enough to help islands remain above sea level this century.

Conservationists working to restore ecosystems and enhance resilience at Tetiaroa Atoll, in French Polynesia, are also aiming to bring back seabirds, says Frank Murphy, director of programs at the Tetiaroa Society. So far, rats have been eradicated on all but one small island, and there are plans to eliminate 80 to 90 percent of the coconut palms.

With the rats gone, island wildlife is starting to change. “We’re getting birds nesting in places where they hadn’t nested before,” says Murphy. Coconut crabs are now abundant, and there has been a huge increase in the number of young sea turtles, which had in the past risked being eaten by rats as they emerged from nests.

Restoration on land will eventually help Tetiaroa’s reefs, according to Murphy. “The effect on the coral reefs is going to be pretty big,” he says, noting the valuable nutrients that will increasingly flow into the reefs from seabird guano.

While powerful storms can wipe out coral reefs and island vegetation, historically, ecosystems have been able to bounce back.

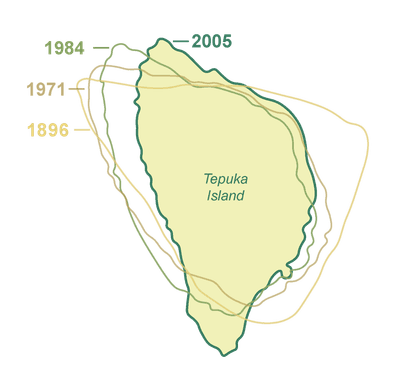

Another aspect of atoll islands can be a challenge for local communities: Many do not stay in place. For example, one side of an island may erode while the other side expands, causing the entire island to move over time. “They change quite rapidly,” says Paul Kench, a National University of Singapore geomorphologist who has collaborated with Steibl. “This cuts right across the way people think about how islands should behave.” Kench led a project that looked at hundreds of atoll islands and found that 40 percent of them are moving.

Overall acreage can also ebb and flow as powerful waves either erode sediment from the coasts of atoll islands or deposit sediment onto islands from the shallow seafloor. On islands with native forests, a tangled web of roots binds sediments together, reducing the risk of erosion.

Haunani Kane, a coastal geologist at the University of Hawaii, and her students are exploring why atoll islands sometimes shrink and sometimes grow by researching islands on Lalo Atoll in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, northwest of the main Hawaiian Islands. The monument is an important habitat for endangered monk seals, sea turtles, seabirds, and other wildlife and is culturally significant to Indigenous Hawaiians.

The changing shoreline of Tepuka Island, part of Funafuti Atoll in Tuvalu. Source: Paul Kench. Yale Environment 360

During a 2018 hurricane, one of Lalo’s islands washed away entirely and another was highly eroded. Now, seven years later, the decimated island has returned and both islands are growing, thanks to wind and wave energy that have delivered new sediment to the island. Kane describes Lalo Atoll as a “natural laboratory” to study how islands are affected by extreme events.

While powerful storms can wipe out coral reefs and island vegetation, historically, ecosystems have been able to bounce back. “Everything on an atoll, the native species, they’re adapted to rapidly recolonize,” says Steibl. However, with climate change fueling stronger storms, it’s unknown if this pattern will continue. “The question for the future really is, how intense do storms become? And how frequent do they become?” says Kench.

As for human communities on atoll islands, as sea level rises and flooding occurs more frequently, the amount of livable area is likely to shrink, and freshwater supplies will be at risk of saltwater contamination. Some islands may become uninhabitable, says La Rochelle’s Duvat, but atoll island communities have adaptation options like houses on stilts, she adds. Not only are elevated houses less likely to flood, but sediment carried by waves can be deposited on land beneath them.

Nature-based solutions cannot help the most urbanized islands, says Duvat. Once engineered approaches, such as concrete seawalls, have been adopted, she says, “these islands have already irreversibly lost their natural adaptive capacity.”

Most atoll islands are lightly populated and can turn to natural approaches. Still, it’s not known if even healthy atoll ecosystems will be resilient enough to survive increasing rates of sea level rise. Scientists agree, however, that if the health of their marine and terrestrial ecosystems is maintained, these islands will be in a better position to survive the century.