The northern Indian state of Uttarakhand, nestled in the Himalayas, is home to a population of 10 million people, mostly farmers. Many are among the 400 million Indians who lack access to electricity.

In recent years, however, a strong push for hydroelectric power development has started to change that. Since Uttarakhand’s rise to statehood in 2000, the expansion of hydropower in the region has mirrored the region’s robust economic growth. Many of the dams that have been built are small hydropower projects that harness the force of a river without trapping large reservoirs of water.

But hydropower’s benefits have come at a cost. In June 2013, early and extraordinarily heavy monsoon rains fell for two days, streaming off Uttarakhand’s mountainsides, overflowing its rivers, and overwhelming scores of new dams. The flooding eventually killed almost 6,000 people, tore up 1,300 roads, took out nearly 150 bridges, and destroyed 25 small hydropower projects. The disaster seemed an act of God, but a government-commissioned said much of the blame lay elsewhere — on the new hydroelectric power infrastructure, which included nearly 100 dams, many of them smaller than 25 megawatts in capacity.

A panel of experts said the huge number of dams and associated construction debris were spaced so closely together that they had changed the river courses and flow of sedimentation, exacerbating the flooding. Tunneling through mountains and deforestation also contributed to the disastrous flooding, the panel said. As the floodwaters roared through narrow gorges where small dams had been built, the torrent swept up uncounted tons of dam construction spoils and carried them downstream, swamping villages, according to a report commissioned by the Indian Supreme Court.

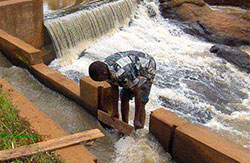

Run-of-the-river projects can provide cheap, off-grid power, allowing rural areas easy access to electricity.

It turned out that one or two of the state’s largest hydroelectric dams — an energy source that for decades has been blamed for serious environmental damage around the world — may actually have held back some of the worst flooding.

Uttarakhand may have been a worst-case scenario for small hydro, but there is nevertheless an increasing understanding that a global push to downsize this renewable energy source carries risks. Small hydro has great potential to bring power to some of the 1.2 billion people around the world who lack electricity, and groups like the World Bank and United Nations are increasingly backing small hydropower projects. But it is not environmentally benign, with impacts ranging from the fragmentation of river habitat to the potential for cascading dam failures during the kind of flooding experienced in Uttarakhand.

Small hydro, which includes so-called mini- and micro-hydro projects on small rivers and creeks, is most often defined as dams with a capacity up to 10 megawatts, though some countries define it as including dams of up to 25 or 30 megawatts. (The world’s biggest dam, the Three Gorges Dam in China, has a 22,500-megawatt capacity). Although designs differ and sometimes rivers do get diverted, small hydro dams are often built as “run-of-river” projects, meaning the flow of the river turns some turbines in the dam to produce electricity without the need to create a reservoir behind those turbines. This can provide cheap, off-grid power, allowing rural areas access to electricity.

So far, about 75 gigawatts of small hydro have been installed worldwide, the bulk of it in China (37 gigawatts), Europe (about 17 gigawatts), and North America (about 8 gigawatts). So how much small hydro potential remains? According to one assessment from the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), the total remaining global potential is just under 100 gigawatts of projects of 10 megawatts or less. That’s equal to 100 nuclear reactors or big coal power plants.

A glance at the specifics of small hydro’s potential sharpens the focus on developing countries even further. East Africa has only 208 megawatts of installed small hydro, with another 6,000 megawatts (6 gigawatts) that could be added; Kenya alone, with less than 2,000 megawatts of installed electricity from any source, could add 3,000 megawatts of small hydropower, according to UNIDO. Southeast Asia also has 6,000 megawatts of untapped potential. (The U.S. and Canada have tapped more than 85 percent of their small hydro potential already, with about another 1,000 megawatts that could still be developed, UNIDO says.)

Although there is still plenty of focus on major dams in certain parts of the world — including scores of large projects in China and numerous megadams in the Amazon — many countries, developers, and financing groups are now more strongly focused on downsizing hydropower. Pierre Audinet, the program team leader for clean energy at the World Bank’s Energy Sector Management Assistance Program, said that the majority of the bank’s current hydropower projects are small. Since 2003, the World Bank reports that 61 percent of its projects were run-of-river or other small-scale or micro-hydro development.

The World Bank is trying to convince developing nations that pushing too fast with small hydro carries risks.

Still, the World Bank is trying to convince developing countries that pushing too fast with small hydro carries risks.

“This whole discussion on accumulating impacts, it is something we pay a lot of attention to, and we have been pressing our client countries to mitigate and prevent the negative impacts that can happen when there are too many dams on a single basin,” Audinet said. In Vietnam, a $202 million commitment from the World Bank is helping finance the construction of nine new small hydro plants — maxing out at 30 megawatts each — with six already completed. The project includes an exhaustive environmental framework that requires numerous safeguards before a project is eligible for funding. These range from assessing impacts on fisheries, water quality, and sedimentation, to consideration of downstream effects.

These precautions are in place for a reason, as the risks of building too many small dams in a single river basin aren’t yet fully understood.

“It’s really tricky because these smaller dams, they don’t have the measurable impacts that you have with the bigger dams,” said Martin Doyle, director of the Water Policy Program at Duke University. “You don’t get the same sediment-starving effect downstream, and a lot of species can actually get by them during floods. But what they do is — we always called it death by a thousand cuts. Instead of having one big Hoover dam, you have thousands of little dams. They add up.”

David Strayer, a freshwater ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, New York, said fragmentation by hydropower is a serious threat to ecosystems. In the U.S., Strayer said that studies have shown small dams mark the boundaries of various freshwater species, such as mussels, with potential long-term consequences. Put a small power project in today, and mussels will likely still live on both sides of the dam tomorrow. But over time, a drought or a flood might kill off the group on one side or the other, and the dam will block the rest of the species from spreading out to fill the void.

“It’s not something that is yet regarded as a primary factor affecting freshwater biodiversity, but we have enough hints of this now that I personally would put this on the short list of major endangering factors over the longer term,” Strayer said.

One study found the cumulative impacts of small hydropower can actually outweigh those of larger dams.

Another study in the Nu River area in China found that the cumulative impacts of small hydropower can actually outweigh those of larger dams. Flow modification of streams, for example, was “3 to 4 orders of magnitude greater” for the numerous small dams than for dams as big as 4,200 megawatts and 300 meters in height. Downstream of small hydro projects — which in some cases actually do divert rivers for large portions of the year — the rivers were “dewatered” an average of 74 percent of days studied, which aside from the obvious problems also can negatively affect water quality. Water quality was also more strongly affected by small hydro than large, the Nu study said.

Two studies — one by a group at Kansas State University and one by scientists at the University of New Mexico — found that some fish species, such as the family that includes carp and minnows, need as much as 100 kilometers of unbroken stream in order to survive and thrive. Many existing and proposed mall hydro projects are spaced much more closely together.

The Uttarakhand disaster represents an extreme scenario. In the report on the floods submitted to the Indian Ministry of Environment & Forests, the expert panel concluded that “bumper-to-bumper” development of run-of-river hydro projects is dangerous, and that changes to sedimentation of rivers caused much of the flooding damage. Even smaller dams hold back sediment and other materials that would naturally flow downstream, which can increase erosion below the dam and make the impacts of flooding worse if dams give way during a deluge, as they did in Uttarakhand.

The report recommended that because of the threat of a “cascading chain of catastrophes,” planners needed to examine the basin-wide impacts of building numerous dams on a single river system. The existing guidelines in the region require only one kilometer of separation between two projects. The report called for a halt to almost all hydropower development until studies could determine optimal distances between dams.

With the help of the UN, the World Bank, and others who increasingly focus on the impacts of small hydro, progress is being made. A survey of professionals working on small hydro around the world, from a database run by the International Energy Agency, suggests most think the industry is beginning to be regulated properly.

“Environmental impact studies are done even here for any sizeable hydro project, but there is room for improvement,” said Terry Gray, a consultant on hydro projects based in Mbabane, the capital of Swaziland. Others in Uganda, Vietnam, India, and elsewhere said that increasingly regulations are being adopted to match a growing demand for small hydro.

“Of course there are benefits to small hydropower, and I’m not saying we should stop doing any hydropower development,” Strayer of the Cary Institute said. “But if you’re really balancing costs and benefits, you ought to be doing so with your eyes open.”