When China — along with Japan, South Korea, Singapore, India, and Italy — was granted permanent observer status in the Arctic Council last month, it left many experts wondering whether a paradigm shift in geopolitics is taking place in the region.

Until recently, security issues, search and rescue protocols, indigenous rights, climate change, and other environmental priorities were the main concerns of the intergovernmental forum, which includes the eight voting states bordering the Arctic and several indigenous organizations that enjoy participant status. But the admission of China and other major Asian economic powers as observer states is yet another strong sign, experts say, that the economic development of an increasingly ice-free Arctic is becoming a top priority of nations in the region and beyond.

“Five or six years ago, most people would have reacted skeptically to the suggestion that China, for example, would become a major player in the Arctic,” says Rob Huebert, associate director of the Center for Military and Strategic Studies at the University of Calgary and a board member of Canada’s Polar Commission. “But in the past few years, China has been investing considerable resources to ensure it will be a major Arctic power. Like other countries now looking northward, it wants to exploit the emerging shipping opportunities and the largely unexploited energy and mineral resources in the region.”

Of those non-Arctic states admitted as observers to the council last month, China dwarfs the others in terms of its economic reach and its global track record of making deals for resource development from Asia, to Africa, to South America.

Iceland twice rejected a Chinese proposal to buy a huge farm, fearing it was part of a plan to build an Arctic port.

To date, China’s economic ambitions in the Arctic have been largely thwarted by Arctic states wary of the country’s claim that the Arctic “is the inherited wealth of all mankind,” and that China has a role to play in its future because it is a “near-Arctic state.” Iceland, for example, twice rejected a Chinese plan to buy a 115-square-mile farm along its northern coast for a proposed golf course resort; the island nation, which is located at the confluence of the North Atlantic and Arctic oceans, feared that the proposal was part of a thinly veiled plan to build an Arctic port.

And last year, European Union Vice President Antonio Tajani flew to Greenland and offered hundreds of millions of dollars in development aid in exchange for guarantees that Greenland would not give China exclusive access to its rare earth metals. Tajani unabashedly called it “raw mineral diplomacy.”

Canada has also been unsettled by China’s reluctance to recognize its assertion of sovereignty over the Northwest Passage.

But Malte Humpert, executive director of the Arctic Institute in Washington, D.C., says China’s interests in the Arctic should not be viewed as fundamentally different than those of major Western nations. “I don’t think there’s any more reason to be concerned about China’s ambitions than there is about anyone else’s ambitions in the Arctic,” he says. “When it comes to environmental track records, it is easy to forget that a lot of the major environmental disasters, such as oil spills, have been caused by ‘Western’ firms.”

Still, the consensus in granting China observer status in the Arctic Council, when a similar application from the European Union was rejected, is evidence of the growing importance of resource exploitation in the Arctic and China’s role in that development.

‘I don’t think there’s any more reason to be concerned about China’s ambitions than there is about anybody else’s.’

Established in 1996, the Arctic Council plays an advisory role by promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction among Arctic States. As a permanent observer, China does not have a vote on the council, but its mere presence means that its voice will be heard.

“It’s not because the Arctic countries have stopped being suspicious of Chinese ambitions,” explains Huebert. “The reality is that China is too ambitious and too big to ignore. The fear is that they would just continue going after what they wanted in the Arctic even if their application was rejected. Who is going to stop them?”

How effectively members of the Arctic Council will be able to influence or constrain the ambitions of China and other Asian powers in the Arctic is an open question.

“The Chinese know that they need us for the resources, but they have also made it clear that when it comes to their core interests, it doesn’t matter who their friends and allies are — they will do what they need to do,” observes Huebert.

Officially, China, whose northernmost territory is as close to the Arctic as Germany’s is, says it does not covet the Arctic for its resources, but rather has a genuine interest in the fate of the region. “China’s activities are for the purposes of regular environmental investigation and investment and have nothing to do with resource plundering and strategic control,” the state-controlled Xinhua news agency wrote last year.

But most experts are skeptical of that contention. China, many experts agree, is eyeing the Arctic for three main reasons, each of which has profound environmental implications.

- China’s economy is heavily dependent on exports. Rapidly melting Arctic sea ice is raising the possibility that a much shorter sea route through the Northwest and Northeast passages will save the country billions of dollars in shipping expenses. The distance from Shanghai to Hamburg, for example, is 2,800 nautical miles shorter via the Arctic than via the Suez Canal.

- In addition to vast reservoirs of oil, coal, uranium, and rare earth minerals, 30 percent of the world’s technically recoverable natural gas and 13 percent of the technically recoverable oil lie above the Arctic Circle. Like other nations, China views those resources as a means to fuel future growth.

- China is also by far the world’s largest fishing nation. With sea ice disappearing, the Arctic may become a new and important fisheries frontier.

China hasn’t been biding its time waiting to hear how its application to the Arctic Council would be decided. In spite of Iceland’s rejection of the real estate deal, China recently signed a free trade agreement with the tiny North Atlantic country and built a new embassy there.

Chinese resource companies have invested $400 million in energy and mining projects in Arctic Canada and they’re promising to invest $2.3 billion and 3,000 Chinese workers in a mammoth, British-led mining project in Greenland.

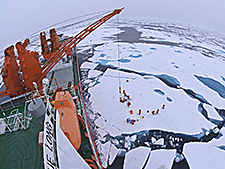

What’s more, China has increased its funding for Arctic research, set up a polar institute in Shanghai, and in 2012 sent the Chinese icebreaker Xue Long through the Northeast Passage above Russia and Scandinavia, presumably to determine the suitability of using that route as a commercial waterway. It is currently building another icebreaker and planning three Arctic expeditions for 2015.

Oran Young, co-director of the Program on Governance for Sustainable Development at the Bren School of Environmental Science and Management at the University of California, Santa Barbara, says many of these developments are an unavoidable fact of life that reflect both the growing global economic importance of the Arctic and China’s position as a pre-eminent economic force. “The Chinese are proceeding in the Arctic in much the same way they are proceeding in other parts of the world, which is largely through economic initiatives,” he says. “They develop connections that offer them the chance to develop natural resources.”

This is especially evident in western Canada, where a third of all investments in tar sands projects since 2003 have come from China. Responding to Canadian concerns, Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper last December placed restrictions on future foreign investments in the oil industry.

Suspicious as some Arctic countries may be of China’s ambitions, each has signaled in its own way that the time for exploiting the Arctic has come. Norwegian and Danish officials said as much at the recent World Economic Forum in Davos, as did Canadian Leona Aglukkaq when she assumed chairmanship of the Arctic Council in May. A key focus, she said, “will be on natural resource development in the circumpolar region.”

The Arctic Council’s Leona Aglukkaq said a key focus ‘will be on natural resource development in the circumpolar region.’

The statements of U.S Secretary of State John Kerry has been a notable exception. At the Arctic Council meeting last month, he told his colleagues that the Obama Administration was making climate change and protecting the environment one of its top priorities. The U.S. “National Strategy for the Arctic Region” lays out a plan that tries to be all things to all interests, including Alaska natives and environmentalists; but it leaves no doubt that economic development in the region is now a priority, although it vows to “exercise responsible [environmental] stewardship.”

The fast-moving developments in the Arctic worry environmental groups such as Greenpeace and WWF, which have pointed out that Arctic states have not adequately addressed the risk of an oil spill and other environmental disasters in the Arctic if resource development and shipping escalates. There are also fears that China — which catches 12 times more fish beyond its own waters than it reports, according to a recent study by the University of British Columbia’s Fisheries Center — could quickly exhaust an Arctic resource that hasn’t even been quantified.

That said, Scott Highleyman, international director of the Pew Foundation’s International Arctic Program, suggests that it is wiser to bring China into the discussions than to exclude it. “Unlike Greenland which can reject China’s plans to build mines, no one can tell China that it can’t fish in the high seas of the Arctic,” said Highleyman.

Oran Young agrees that a more inclusive approach is required if the fragile environment of the Arctic is to be protected.

“The Arctic gold rush that many people were predicting a few years ago is cooling a little thanks to developments such as shale gas exploration,” he says. “That doesn’t mean that the Arctic is not going to be subject to development, but now we at least have a little breathing space to explore a number of different mechanisms that allow non-Arctic states with interests in the region to be consulted.

“It is probably a good thing that China has been granted observer status in the Arctic Council. In that role, it can’t vote, but its voice and its intentions can be heard.”

To the Arctic Institute’s Humpert, bringing China into the discussion of the Arctic’s future is important. “Allowing China into the Arctic Council is a way of including China in the cooperative debate of the council,” he says. “Overall, I think there should be less focus on China and it’s, after all, legitimate economic interests, and more focus on ensuring that any development, be it Chinese or otherwise, is conducted to the highest environmental standards.”