Scientists say the project is a living experiment to understand what works and what doesn’t in wetlands restoration.

The goal of this work is to reverse the damage created by an ill-conceived project in the 1980s that aimed to convert Prime Hook’s salt marsh into a largely freshwater impoundment system, in part to attract more ducks, geese, and other birds for hunters and birdwatchers. But what Rizzo and others see at Prime Hook is more than the resurrection of a single marsh. They see a model for restoring vital wetlands worldwide by taking design cues from nature to recreate a resilient ecosystem — an increasingly vital task as climate change threatens coastlines with rising sea levels and stronger storms.

Scientists working on the Prime Hook project say it is a living experiment to better understand what works and what doesn’t in wetlands restoration. To that end, they have developed a sophisticated monitoring system that records water flow, dissolved oxygen levels, sediment flow, and other key markers. The goal is to rebuild a healthy tidal marsh with meandering channels, lush salt-tolerant grasses, and mudflats that attract a rich diversity of fish and birdlife.

“Every restoration is basically a research project,” says Chris Sommerfield, a University of Delaware oceanographer who is tracking sediment flow in and out of the refuge, a key to building habitat for grasses. “Every site is different. Every time we do a restoration we learn a lot that we can translate into better restoration practices. That’s important because we will be restoring wetlands forever.”

Wetlands are one of the most valuable and diverse ecosystems on the planet. Yet because of development, pollution, and the effects of climate change, they are disappearing at an accelerating rate. A major study released this week on the destruction of ecosystems and the loss of biodiversity said that more than 85 percent of the world’s wetlands have been lost since 1700.

Refuge manager Al Rizzo looks over an area planted with native Spartina grasses. Jim Morrison/Yale e360

A key element in reversing that trend will be efforts to revitalize degraded marshes and devise strategies for protecting coastal wetlands as sea levels rise. And what researchers have confirmed in recent years is what land managers have been seeing anecdotally: Coastal wetlands, when preserved or restored, reduce flooding and erosion better than hard infrastructure like seawalls and levees. And they do it at a lower cost. In one recent study, researchers found that wetland restoration provided $8 in flood reduction benefits for every $1 invested. The study also found that solutions such as marsh and oyster reef restoration could help prevent more than 45 percent of flood damage over a 20-year period in the Gulf of Mexico alone, saving more than $50 billion.

But that’s only a portion of the value of wetlands. Although they cover less area globally than forests, wetlands sequester carbon more efficiently than woodlands. In a 2018 paper, Sommerfield valued carbon sequestration of tidal wetlands in the Delaware River estuary at $42,000 per square kilometer. The researchers noted that the estuary lost about an acre per day of wetlands from 1975 to 2011.

A quarter of Delaware remains wetlands. Like many states, it has a plan to conserve and restore them. The state is also a signatory to the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, which seeks to create or reestablish 85,000 acres of wetlands and improve the health of another 150,000 acres in the bay by 2025.

Programs to rebuild wetlands are gaining momentum globally. In Europe, a seven-year project aims to restore wetlands and connect former floodplains along the Danube River. In China, which has seen its wetlands rapidly disappear in the face of soaring economic growth, an ambitious plan has been launched to restore nearly 9,000 acres of wetlands north of Shanghai. In Australia, the government of New South Wales, working with The Nature Conservancy and the Nari Nari Tribal Council, has launched a major project to restore 210,000 acres of wetlands in the Murrumbidgee Valley. In England, an initiative on Wallasea Island is seeking to repair more than 1,600 acres of wetlands by recreating an ancient landscape of mudflats and salt marsh, lagoons, and pasture.

The Ramsar Convention signed by 168 countries calls for a “wetland decade” from 2021 to 2030 to restore and preserve wetlands. In the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has created a wetlands Restoration Center, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, long builders of human-centric infrastructure solutions, has begun an Engineering With Nature Initiative.

Humans messing with the hydrology of the Prime Hook refuge had created an unnatural disaster.

Engineering with nature is how Rizzo and Bart Wilson, Prime Hook’s restoration project manager, describe their approach to restoring nearly half of the refuge’s 10,000 acres. The Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1963, and until the 1980s, it remained a healthy East Coast salt marsh. Then, managers decided to convert a portion into a freshwater marsh with large areas of open water to attract more migratory waterfowl, among other things. Tide gates were installed across creeks and a canal, reducing the flow of saltwater from Delaware Bay. Freshwater surface runoff was allowed to increase.

A series of storms starting in 2006 opened breaches in the refuge’s line of dunes, inundating the re-engineered system with saltwater, which killed the marsh grasses and turned a healthy riparian forest inland into a ghostly wasteland of skeletal trunks. A county road running through the refuge to a strip of homes on the beach flooded nearly every high tide. Saltwater crept into nearby farm fields, rendering them useless. The cycle of algae bloom and death led to fish kills.

“It was a stink hole,” Rizzo says. Humans messing with the hydrology of the refuge had created an unnatural disaster.

The current restoration project, funded with federal money through the Hurricane Sandy Disaster Relief Act, involves a long list of state and federal agencies, as well as conservation groups such as Ducks Unlimited, The Nature Conservancy, and the Delaware Nature Society.

The $38 million restoration plan involves rebuilding beaches and dunes and restoring nearly half of Prime Hook's 10,000 acres to salt marsh. Jim Morrison/Yale e360

Rizzo and Wilson hired private contractors to do extensive hydrodynamic modeling, relying on data that had been collected in the decade since the 2006 breach. Their goal was to let nature dictate their course, and the models said the best way to do that was to restore the natural hydrology so water levels would drop and recreate the marsh.

Jeff Tabar, a senior coastal engineer with the global design firm Stantec ran the models with his team. “This scale of modeling had not been attempted before,” says Tabar, who has worked on projects from New England to the Gulf of Mexico. “The intent was to have this design process and project be a template that could be used elsewhere for refuges, preserves, and restoration projects.”

Running models requiring computer calculations that took weeks to complete, they evaluated 12 scenarios. What if they closed the breaches inundating the marsh with saltwater? What if they did nothing? What if they closed the breaches and created an inlet between the Delaware Bay and the refuge? In all, the team spent a year running, adjusting, and re-running the models to produce a design.

“You need to understand what’s broken,” Wilson says. “If you can’t understand that, you can restore it and it will revert right back.”

“Our objective is to allow the system to adjust itself and work based on normal coastal dynamics,” says the refuge manager.

What they found was the refuge didn’t have an elevation problem; it had a plumbing problem. If they closed the breaches in the dune and opened the waterways through the refuge based on historic tidal channels, the water levels would go down rather than being trapped in impoundments. Sediment would flow to create mudflats, setting the stage for vegetation to recolonize. Researchers needed to know whether there would be enough salt to grow and sustain a salt marsh. They needed to get the water levels right for Spartina grass to grow. They needed enough sediment on the land side of the dune to build a platform for vegetation.

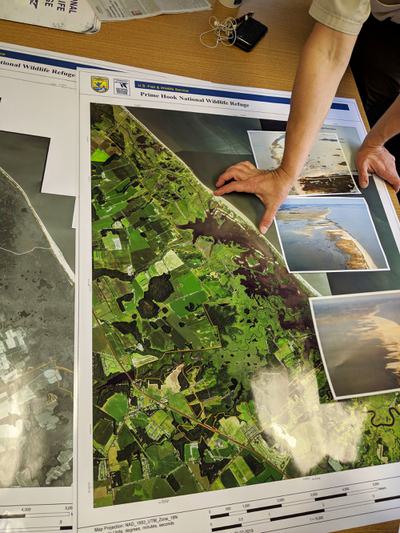

“Modeling doesn’t hold every answer,” Wilson says, standing over before-and-after aerial photos of the refuge in a conference room, “but it puts you on a path using science to set you up for a good design and better success.”

Restoration work began in October 2014 with the closing of the breaches by constructing the beach and dunes. The restored dunes are now nearly 10 feet high, allowing for overwash that will dissipate storm energy. Behind it, they built a platform of sand planted with grasses extending into the marsh. When the dune naturally migrates inland, rolling over from wave and storm action, it will have a place to land.

A plane scattered Spartina, millet, and other seeds over 1,000 acres. Later, workers disseminated smaller seedlings by hand. A dredging company created what Rizzo calls the neural network of the refuge by digging 25 miles of channels so water would flow as it once had.

The transformation of an area of Prime Hook from 2015 t0 2017 following dune building and planting of native grasses. USFWS

So far, the results are encouraging. Birds have returned, including a variety of ducks that hunters feared were gone for good. Eels, bass, crabs, perch, flounder, and other fish are increasing in numbers. But the project is still young. “In terms of the long-term trajectory, it’s too early to tell,” Sommerfield says. “It will be another 10 years to know if the grasses are growing in the right location at the density to keep the landscape stable.”

On a spring afternoon with an easterly wind blowing water into the marshes, Rizzo pulls over on Prime Hook Road, the refuge’s central artery. An electronic sign at the road’s entrance that warns drivers when it is flooded hasn’t blinked since the restoration; the marsh is once again naturally absorbing high tides and storm surge.

“It’s pretty amazing we have as much regrowth as we do,” Rizzo says. Small circles of Spartina alterniflora that sprouted naturally dot the dark mudflats. Along the channels, grasses grow thicker. Phragmites, a non-native invasive grass, grows along the edges of the Spartina stands, but it’s been sprayed with herbicide, one of the few nods to continuing intervention.

“Our primary objective was to set the table to allow the system to adjust itself and work based on normal coastal dynamics,” says Rizzo. “What we’re doing now is sitting back and watching.”