Widespread planting for bees and other pollinators by landscape designers and gardeners is already underway.

Tonietto, a biologist at the University of Michigan-Flint, is co-author of a recent essay in Conservation Biology that points to research on urban bees as evidence that humans can share high-density habitat with other species. “Surrounded by increasingly less hospitable rural and suburban landscapes,” she and her colleagues write, the city “can become a refuge” for the bee species and other insects that are suffering significant declines.

“This means we can do some real conservation in cities,” not just public education and outreach, says Damon Hall, lead author of the essay and a biologist at Saint Louis University.

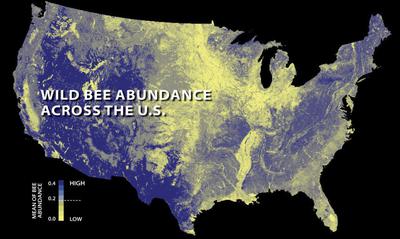

According to a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, from 2008 to 2013 bee abundance in the United States decreased most sharply in the Midwest corn belt and California’s Central Valley, where agricultural production has intensified. “Among the numerous threats to wild bees, including pesticide use, climate change, and disease,” the authors write, habitat loss seems to have been the biggest contributing factor. “We’ve got to find a way out of these declines,” says Hall, “but in the interim we have an opportunity within cities to support and bolster bee habitat.”

The abundance of wild bees across the U.S. in 2013, with areas of yellow showing where bee populations have declined. Koh et al, PNAS 2016

Widespread planting for bees and other pollinators by landscape designers and gardeners is already underway. The orange dots marking the locations of new pollinator plantings blot out most of the map of the U.S. on the website of the Million Pollinator Garden Challenge, an initiative launched in 2015 by a partnership of conservation, gardening, and civic groups and designed to create gardens and landscapes conducive to bees, butterflies, and other pollinators. Pollinator gardening is becoming mainstream in the U.K., with the meadows of the London Olympic Park its most public face. Echoing other proponents of pollinator gardening, Vicki Wojcik, research director at the nonprofit Pollinator Partnership, says, “People find planting for pollinators inspirational, because you really do feel like you are making a difference.”

Are urban gardens encouraging the spread of aggressive non-native bees that could outcompete declining natives?

Amid the heartening news about urban bees, however, some uncomfortable questions are being raised. Can the non-native plants used in most gardens harm remnant native plant populations in urban settings, many of which harbor threatened species? And are urban gardens encouraging the spread of aggressive non-native bees that could outcompete declining natives?

Remarkably little is known about wild bees, an astonishingly diverse group of more than 20,000 species worldwide. In the U.S., bees range in size from the hefty carpenter bee to tiny Perdita minima, a Southwestern native less than .08 inch long. In addition to flowers, bees require places to nest. Unlike the European honeybee, which lives in hives, most bees are solitary and nest in tunnels they excavate in soil or wood.

Imagine you are a bee attempting to navigate an urban landscape. If you are one of the many species that needs bare ground for nesting, you are out of luck, since city soils that have not been paved over or obliterated by buildings are often covered by dense turf or pounded down and impenetrable due to human foot traffic. Flower patches must be within flying distance because you need to return to your nest several times a day carrying pollen and nectar — a task made all the more difficult by the fragmented nature of urban green spaces. Even if you are a diminutive bee that can fulfill all your needs in a small area, your nest may be so far from those of other bees that inbreeding and, eventually, local extinction are inevitable, says U.S. Agricultural Research Service entomologist Jim Cane.

Lurie Garden in Chicago’s Millennium Park is a “near-native” representation of prairie habitat. Jo ana Kubiak / Lurie Garden

One big advantage of urban areas is that people, like bees, are attracted to flowers — “the key driver,” in Hall’s words, “of bee diversity and abundance.” Although the native vegetation has been all but wiped out, the diverse human populations in cities plant flowers from around the globe. That’s a boon for generalist bees, which are not fussy about flower forage. But if you are oligolectic, a specialist that requires pollen from one group of closely related native plants, or even a single species, you “are doomed,” says Cane.

As a result, in the typical city most of the floral specialists and many ground-nesting bees are missing, leaving what Cane calls a “subset” of the larger regional bee fauna. Thirteen percent of New York State’s bees were found in New York City community gardens. Half of Germany’s bees were discovered in Berlin. Interestingly, bees are flourishing, particularly in vacant lots in so-called shrinking cites like Detroit and Cleveland. Hall attributes this to the undisturbed “wildness” of these seemingly forlorn places. “No one’s out there spraying a bunch of Roundup or neonicotinoids [pesticides],” he says. “Few people live there.”

Scientists have also documented threatened species in cities. For instance, researchers who studied bees within a third of a mile from the center of Northampton, a large, urbanized English town, found the nationally rare sharp-tailed bee Coelioxys quadridentata and discovered that overall bee abundance and diversity were higher in the urban core than in surrounding meadows and nature reserves.

Gardens along New York City's High Line, a former elevated railroad track transformed into a 1.5-mile-long park lined with native and non-native plant species. Friends of the High Line

More than a century ago, landscape architect Jens Jensen spurred a homegrown rebellion, pioneering a new approach to landscape design in Chicago’s parks based on native plants and regional plant communities like those found on the prairie. Today, the debate over growing native or non-native plants continues.

“The reality is that most urban and suburban gardens have had no or minimal natives,” says Mary Phillips, director of the National Wildlife Federation’s Garden for Wildlife program. Educating the public about the importance of reestablishing native plant populations is a priority of efforts like Garden for Wildlife and the Million Pollinator Garden Challenge, she says.

The Lurie Garden, a stylized “near-native” representation of prairie habitat by superstar Dutch plantsman Piet Oudolf, has been called “a possible resolution” to this debate. Some 26 percent of its plants are native to the state of Illinois. According to a recent Lurie Garden blog, “Current research indicates that mixing native and non-native plants in a designed landscape increases pollinator habitat.”

Beyond establishing that such gardens sustain mostly generalist bees, however, research paints a more complicated picture. Just as studies have indicated that native trees and shrubs provide the most resources for birds, surveys have found “a relatively low attraction of bees, especially native bees, to exotic plants.”

What’s more, in a recent paper in New Phytologist — “Considering the Unintentional Consequences of Pollinator Gardens for Urban Native Plants: Is the Road to Extinction Paved with Good Intentions?” — University of Pittsburgh biologists found that the non-native and native plants used for pollinator habitat could have a variety of deleterious effects not only on urban native plant remnants but also the native bee specialists that depend on them. Unless they are grown from seed collected locally — almost never the case in commercial horticulture — native plantings could swamp unique gene pools in nearby urban fragments.

A bumblebee on the flower Asclepias tuberosa, also known as butterflyweed, which is native to Illinois. Jason Kay

Even worse, the non-natives have a high potential to escape from cultivation. And as research has demonstrated, there is often a lag time of several years to several decades between the arrival of an exotic plant and the explosion of its populations, making it difficult to conclude that a non-native that has been innocuous for years is safe to plant.

Exotic plants may also be favoring the non-native bees currently proliferating in cities. Scientists suspect that some of these bees may be poised to expand their territories and potentially displace native bees with widespread pollinator plantings. According to University of Virginia entomologist T’ai Roulston, an estimated 41 non-native bee species are currently in North America. One species that has raised a red flag is Osmia taurus, a Japanese mason bee that potentially could outcompete the native blue orchard mason bee, an important pollinator of apple and cherry trees.

“I have collected more Osmia taurus at my field station than all but one of the nine native Osmia species,” Roulston says. Meanwhile, entomologists point out, in U.S. cities the much-loved non-native honeybee consumes more floral resources than any other species, dominating native bees wherever a hive is nearby.

Bee advocates say the planting of native species essential to the survival of specialist bees should be a priority.

Few scientists believe that urban habitats are a panacea for bee conservation, although they do support some important populations. In the words of Tina Harrison of Rutgers University, who studies the homogenization of bee communities in disturbed landscapes, “Pollinators that are successful in cities are often very common in other habitats in the surrounding region,” and a focus on conserving them could divert much-needed funds from efforts to protect vulnerable bees. Conserving regionally rare or specialist bees that have found a refuge in cities, though, is probably a good idea, she says.

There is unanimous agreement that much more can be done to make cities beneficial to bees by, for example, ensuring that there is ample bare, loose soil for ground nesters and following the French government’s lead in banning pesticides that are harmful to bees. In addition, bee advocates say that urban native plant remnants should be protected, and the planting of native species essential to the survival of beleaguered specialist bees should be a priority.

As the Pollinator Partnership’s Wojcik points out, the sheer per capita conservation potential of cities is tremendous. “If everyone in a city of a million people planted even one pollinator-friendly plant,” she says, “there would be a million more foraging opportunities for bees.”